DOOM is good, to general incredulity.

The whole world is loudly, vocally, relentlessly amazed. DOOM is good! Unbelievement! Dumbfoundery! Getouttaheah!

It occurs to me how cruel and backhanded this startled praise must feel to the developers. I mean think about it: You did your job well. Everyone is astonished. What a shitty compliment.

That surprise is not entirely baseless. DOOM had a… complex development, haunted by corporate changes and the specter of its predecessor. It also had the future to deal with: the future of shooters is .

Harvey Smith and Cliff Bleszinski say the future of shooters is RPGs. Bobby Kotick probably says it’s totes Modern Warfare, lots and lots of Modern Warfare. Others may have opinions of their own. Whatever the future of shooters, though, the feeling has long been that the DOOM franchise is part of their past.

As assertions go, that’s subjective to the point of being unfair; if it also feels demonstrably true, that’s because it (A) is and (B) could not be otherwise. You can’t have something without a first thing, but the first thing is the spark. The spark is not the fire; the spark begets the fire. The “shooter” owes its existence to DOOM, but the direct influence of a genre’s nativity reasonably dwindles as innovation brings newer and newer stuff to the fore. I Love Lucy is not the future of sitcoms. Don Quixote is not the future of the novel. Zork is not the future of adventures. And DOOM is no one’s future of the shooter.

DOOM has always looked like the the future of the shooter. It still does! Behold DOOM 2016:

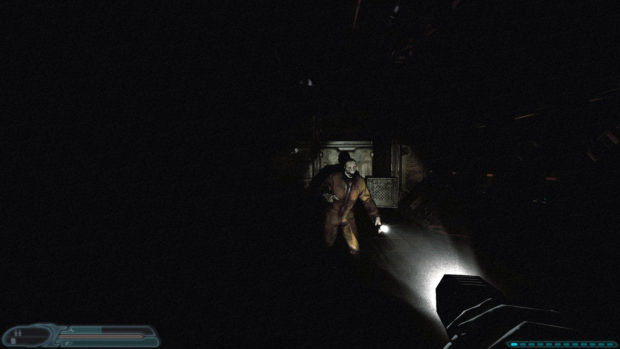

Looks aren’t everything, though. Let us ponder the lesson of DOOM 3: the consensus is that installment, released in 2004, tarnished the whole franchise. It didn’t — not really — but DOOM 3‘s shortcomings are the chief reason people are so surprised by DOOM 2016 (officially just called DOOM, for maximum confusion). The public built fortresses of doubt based on its broad assumptions about id Software’s capabilities as a developer, given its recent history with the franchise. That, and that alone, is what led to dubious feelings about DOOM 2016.

The worst indictment of DOOM 3 is that it felt un-modern. It looked modern but played like a decade-old throwback. 2007 players looked at DOOM 3 and saw glacial pacing, trite level design, tedious play, and galling mechanics. It suffered from a distinct lack of adrenaline, which threw us all for a loop because this is DOOM we’re talking about. And though none of these things were bad in and of themselves, they were bad design decisions, at least for that game.

Meanwhile, id’s revolutionary Tech 4 engine revolutioned itself straight past 2004 silicon. The most powerful GPUs of the day struggled to render Tech 4 in anything close to reliable real time. Dialing down the visual fidelity would improve performance but undermine Tech 4’s viability as a licensable engine. DOOM 3 had already been delayed by more than a year, and time had not stood still. With each passing day Tech 4 looked less like a miracle and more like its competition. They needed a way to retain overall graphics quality while reducing hardware burden.

Enter Flashlight.

This guy has a flashlight too. I have a flashlight, you have a flashlight, let’s all have flashlights together.

If it lay outside that flickering circle, it needed only passing attention from the GPU. The idea worked (almost) because DOOM always had its horror elements, and horror was what id had really wanted to push here anyway. They wanted it to feel like grinning demons lurked in every shadow, and to its credit, DOOM 3 was often terrifying. There were just so many shadows in which grinning demons might lurk. Wrapped in its inky cloak of blackness, DOOM 3 brought palpable tension and a swarm of jump scares. But it was too dark, almost unplayably dark, and constantly switching between weapon and flashlight got tiresome.

Posterity will remember DOOM 3 more kindly, I suspect. It was not a bad game. In some ways it was a great one. It just can’t be seen that way right now. The outsize reaction to DOOM 3’s shortcomings had little to do with the actual scale of its flaws. It was based on the anticipation complex collectively crowd-wisdomed into being by a very excited audience. By the time it did come out, many people were so excited nothing would have pleased them. Players didn’t feel let down, they felt betrayed. And they saw id Software as the author of this treason.

Thus expectations for DOOM 2016 were distorted. The audience’s collective mind expected — wanted — to despise it. Ever since DOOM was announced, and based on very little concrete evidence, the widespread assumption has for years been that DOOM would be bad.

DOOM is good, to general incredulity.

To a great extent, DOOM feels like an intentional repudiation of the earlier game. Everything DOOM 3 does, DOOM 2016 does the opposite. The real genius is that it in owning its identity, it sheds its past. DOOM digs its claws into its old-skoolery, eschewing anything not fundamental to itself. It’s a balls to the wall corridor shooter released into a world that hasn’t equated shooters with balls or walls for some time.

Equal measures visceral action and plain viscera, it abandons the horror stuff entirely. Imperfect but gleefully absurd, DOOM is a joyous splatterdrome, a totally shameless delicatessen of carnage serving up clever innovations right alongside reliable tropes that never went out of style.

“Steerpike,” you ask, “What do you do in DOOM?”

You SHOOT STUFF is what. Hell Stuff. You shoot Hell Stuff. Also you strangle Hell Stuff and curb-stomp Hell Stuff and use your thumbs to pop out Hell Stuff’s Hell Eyeballs and sometimes beat Hell Stuff to death with its own severed Hell Arm because by Memnoch, the only good Hell Stuff is dead Hell Stuff.

“How do you know the stuff you’re shooting is from Hell?” you ask, quite reasonably.

Because it tells you.

“DEMONIC INCURSION AT CRITICAL LEVEL,” a crisp voice announces.

Well obviously.

Generally you might think that any level of demonic incursion should be considered critical, but in DOOM that’s not strictly true. It turns out some levels of demonic incursion are really quite tolerable. Employees of the Union Aerospace Corporation know this better than anyone, they are connoisseurs of demonic incursion. Because at the UAC’s Mars facility, they’ve dug a little tunnel to Hell.

Actually I think it’s maybe not that little.

They’ve dug a tunnel of indeterminate size to Hell. Demons incur therefrom.

Is this a terrible corporate secret? Scientific hubris run amok? Must this be contained at all costs? Should not someone be alerted? An evacuation ordered? A frantic distress call issued? A sternly-worded letter written?

FUCK NO

There’s no point in any of that because it’s not a secret. Everybody knows about it. The UAC describes the tunnel to Hell in all its handouts. The tunnel to Hell is a major part of the company’s brand strategy. Union Aerospace has dug itself a Hell Well, which it uses to slurp Hell Energy (“HELL ENERGY AT CRITICAL LEVELS” says the voice) into… I don’t know… into This Universe I guess. And they put the Hell Energy into boxes or barrels maybe and ship it back to Earth because Hell Energy, you see, Hell Energy is clean-burning and affordable, and thanks to the miracle of Hell Energy humans can drive SUVs and leave the lights on and run the dishwasher endlessly. Hell Energy FTW!

The only problem with Hell Energy is Hell Demons sometimes come with it. You know, from Hell. Which is a drawback, but really… which is worse: critical-level demonic incursions, or smog?

DOOM takes itself exactly that seriously.

Offshore intakes for nuclear power plants occasionally suck in schools of fish (divers too). I imagine a similar setup at the UAC facility, except instead of fish it’s schools of demons, just doin’ their thang down in Hell, when suddenly they’re inhaled by that dark maw and hurled into blackness, spinning headlong, bouncing off walls and each other, thrashing and gasping for breath, arms and tentacles flailing, and just when they think they can take no more they’re ejected — plort — out into, like, a Hell Energy Retaining Pool, and they come sputtering to the surface, battered and dizzy and frightened, and people are all around waving sticks and nets, and the demons all like, “What the crap just happened,” and the people are all like “Shut up Hell Demon, get in my net,” and the demons are like “Wait what” and the people are jabbing them with their sticks and the demons are like “quit poking me, also where’s Frank, I saw Frank a minute ago, Frank are you hurt” and Frank calls over from the other side of the pool “I’m here, I’m over here,” and the computer voice is all “DEMONIC INCURSION AT CRITICAL LEVEL” and the demons are like “We didn’t incur, you sucked us into your stupid pool” and somebody — probably Frank — wonders if it’d be possible to put maybe a heavy screen on the Hell end of the Hell Energy Pipe, and also some signs that say Hell Energy Intake — Do Not Approach, you know, Frank is saying, safety first, and the demons have a pretty good point there and then a dude in a Halo-looking outfit comes in and blasts the shit out of them.

“DEMONIC THREAT ELIMINATED,” says the voice.

A gun nut buddy of mine decreed that the shotgun doesn’t look futuristic enough. “Shouldn’t it be a space shotgun?” he asked. But I don’t know what that means exactly.

It’d be easy to dismiss DOOM as badly written, but the fact is, it takes a certain level of authorial talent to write something so self-referentially ludicrous. DOOM is not badly written, it is quite skillfully written. Like everything else about itself, it owns its absurdity and makes no apologies for it. The guy who wrote DOOM is good enough to make it seem rollickingly bad, but not in a bad way.

Back in 2008-ish when this game was first announced, British novelist Graham Joyce was attached to write the script. I was pretty excited about that because I am a fan — his debut novel The Tooth Fairy is a year’s worth of nightmares — and he struck me as a compellingly unexpected choice who would bring something distinct and potentially brilliant to the property. But Graham Joyce was diagnosed with lymphoma in 2009 and died five years later at the tragically incomplete age of 59 without ever getting a chance to contribute to the project. To say that this DOOM is decidedly un-Joycian is a monument of understatement, but I get the feeling Joyce would have liked what the game turned out to be. It wouldn’t have been what he’d write, but he’d appreciate the effort that went into it.

This screenshot has no purpose other than to break up the text block. Also I thought it was pretty. Green is a very rare color in DOOM.

If you’ve played a lot of shooters, you’ll find DOOM both comfortingly traditional and surprisingly fresh. It’s fresh in its traditionalism. Obvious mechanics have interesting twists, and others are pared down to the essentials.

You run. I’m not even sure you can walk. Why would you? Dude, demonic incursion’s at critical level. Hoss your freight, for god’s sake. Besides, everyone always sprints in shooters.

Which leads to the next point: if you’re not shooting something, that’s DOOM’s way of telling you you’re lost. Actually if you slow down at all for any reason that’s DOOM’s way of telling you you’re lost. Shooter stuff that bummers the pacing is out. Reloading? Realistic, yeah, but realism is sort of out the window what with the Mars/Hell thing so let’s just pretend future guns never need reloaded.

Aiming.

Are you kidding? Just click the button, violence muffin. “Aiming.” Honestly, kids these days.

Damage: practically every enemy is going to hurt you a little. That alone is unusual for shooters. To compensate, enemies almost always drop health; if you want more health, you have to be impressive. Shoot a fire imp? Health. Pop a fire imp’s head between your fists like a bloated tick? More health.

It’s kinda hard to tell in this shot but basically I’m fisting this dude’s mouth in anticipation of pulling some part off of him. Jaw, tongue, I’m not sure. Something’s coming off.

That’s the “glory kill” mechanic in DOOM, focus of many a YouTube compilation. It’s pretty simple: hurt an enemy really bad to stagger them, then scamper up and drive your thumbs into their ears or punch their spine out or whatever. The whole enterprise quickly becomes more mundane than glorious since you’re going to try it with practically every enemy you encounter. That’s one of the only times DOOM doesn’t get something right in its execution.

Oh! The chainsaw. Yeah, it’s in there. If you want enemies to drop ammo instead of health, use the chainsaw. Why? Who cares? Demonic incursion! Critical level! Make with the damned chainsaw! Jeez, next you’ll want to know why Mars has chainsaws in the first place.

Mars has chainsaws so you can do this:

That… might… not… actually be a chainsaw kill. I think maybe this fellow just exploded when I hit him. Happens sometimes. Demons are fragile little gore piñatas. Imagine this, with a BRRRZZZZ sound, and there’s the chainsaw.

DOOM is simple, and proud of it. That, also, could be taken as a backhanded compliment, but it’s not intended as one. I wouldn’t want every game, or even every shooter, to be like this. Still, there’s an earnestness in this experience, and touches of design brilliance that, honestly, nobody ever really associated with id Software.

That was a backhanded compliment.

But what is id Software today? Once upon a time, a whiff of a hint of an opinion out of Dallas was enough for hardware roadmaps to be rewritten, trends and directions to materialize or vanish. Once upon a time, the phrase “game engine” was synonymous with id Software. Today no.

The most seismic change for id was the departure of co-founder and technological ubermind John Carmack in 2013. Second most: the studio’s acquisition by ZeniMax Media Group. What ripples these events caused have been largely invisible to the gaming public, and DOOM’s solidity will actually probably reinforce that. Had DOOM failed or sucked, which — don’t lie — we all expected it to, id’s fate would likely have been a quiet absorption into other ZeniMax properties. But since DOOM did not fail and does not suck, the future looks brighter.

As I work my way through the latest trip to Mars and then Hell and then Mars again, I see two things clearly: first, a really worthwhile, well-executed game. Second, a glimpse of an alternate past — one in which DOOM 3 maybe wasn’t universally lauded, but wasn’t universally reviled either. DOOM 2016 is not a work of deathless genius or anything like that, it’s just a good game.

To general incredulity.

![]()

Send Army of Darkness sound WADs to Steerpike@Tap-Repeatedly.com.

Oh man, I miss your writing Steerpike. This made me laugh out loud: “[…] thanks to the miracle of Hell Energy humans can drive SUVs and leave the lights on and run the dishwasher endlessly.”

I finished Doom… last week, actually, after a good 40+ hours mastering everything, completing all the rune challenges and fully upgrading everything. Go Doom Marine! Ultra violence was a great challenge.

A couple of your points I disagree with. Firstly, I think Rage was also to blame for the ‘fortresses of doubt’ surrounding Doom (I haven’t played Rage yet). Secondly, the glory kill mechanic is glorious EVERY TIME. I equipped the rune that speeds them up so I could pop those suckers in a heartbeat. They’re contextual so there’s a surprising number to see when you’re doing your glory killing rounds.

I wish Doom had kept that self-aware irreverent tone that seemed so prominent early on (punching screens, ignoring advice and breaking stuff etc.) because by the end it seemed a lot more by-the-numbers with the Doom Marine always towing the line. And that disconnected voice you hear in the Hell dimension just sounded so terrible. Overwritten and overacted. Okay, it may have been intentional but it still sounded terrible. Like Christian Bale in the Batman movies.

Finally, I think the thing that makes Doom so clever relates to the glory kills in that instead of just running backwards and shooting all the time (like you do in most old-school shooters), you’re running backwards and shooting but then you’re moving in for those melee kills, constantly. There’s a real riotous rhythm to Doom that often left me breathless. The level design and mantling and double jumping just work so well here too. It all fits together perfectly. Oh, and the engine is silky smooth. I’ve not been so impressed with the tech in a long time. John who?

Another thing Steerpike, when you get to the hell levels, pay attention to the use of light and shadow, in arenas and in the backgrounds. It’s striking and makes the whole place look like a painting. The folks responsible for the lighting deserve a rise!

I watched TB play some of this and my first reaction to the “Demonic Infestation at Some-Such Level” message was “What exactly is an acceptable level of demon infestation?”

You can hold Shift to walk.

I have no idea why.

LOL, thanks Megazver — I’m glad there’s at least an option to walk, because there’s plenty to look at.

Gregg, Tech 6 was created by John Carmack; as far as I know development work on the engine was done before he left id to join Oculus VR. Tech 6 has been in development since shortly after Tech 5 (which powered Rage) and as you say, it’s an amazing piece of work. The attention to detail made possible by Tech 6 is stunning, and most levels make great use of the lavish special effects and lighting. Really the only complaint I can come up with about DOOM’s graphics is that they look so good that a ton of “background” stuff actually looks like stuff you can interact with. Beyond that, its performance and aesthetics are incredible.

I’m just inching my way through DOOM (I only just made it to Hell actually) but I’m enjoying it immensely. To clarify, the concept and mechanics of the glory kills aren’t repetitive, it’s the visual process. I agree, the yo-yo of fight-advance-glory kill-back up-fight is great. It keeps combat very fresh in what could otherwise become kind a of a dull experience. I’m really looking forward to seeing more.

I still find it weird that John Carmack is no longer with Id.

Nice write up of the latest Doom…props. You have a way with words.

The writing is bloody brilliant, in my humble. “The road to hell is paved…by United Aerospace Corporation.”

Great article, Steerpike, as always–been missing your prose!

To me the thing that can’t be overstated about Doom is that it is _fun_. That’s the primary characteristic of the game. Killing motherfucking demons and having motherfucking fun.

Sometimes developers forget the importance of fun. I love ambition, I love games that push the envelope of design and especially of my understanding of what play means, but the best games can do that while never forgetting to be fun. I can forgive a lot of flaws if you deliver the fun.

Don’t know if I mentioned this in the forum, I probably did, but, related to the glory kills and whether their visual spectacle becomes normalised and/ or boring towards the end of the game, I’d like to expand on what Gregg said: one of the most important aspects of Doom 2016 is how much it empowers the player through sheer ease, speed and responsiveness of movement. It is a shooter game and it does the shooting part brilliantly, but the original Doom, way back in 1993 gave birth to the whole genre not just because it had massive guns but because it had vas and (for the time) complex spaces that you moved through like a greased lightning. Carmack, Romero and the gang were very much into d’n’d, and digital renditions of RPGs were for some years already working in first person, showing the player massive dungeons to traverse, explore and fight in, so Doom (rather than Wolfenestein 3D that was more a proof of concept in this regard) just took this to an entirely next level empowering the player through speed and ease of movement. Suddenly your Might’n’Magic, The Bard’s Tale and Ultima experiences turned into vivid dreams of owning the space, running up to the demons and shooting them in the face, backpedalling out of danger like some kind of amphetamine athlete etc. Doom 2016, among other smart things it did to reinvent the 1993 gameplay, absolutely understood the need to keep you moving at high speed at all times and glory kills are an important tactical consideration in this regard. This is an almost rebellious game in today’s shooter landscape since so many modern shooters tend to rely on tactical use of cover and careful movement between cover in order to preserve health. For Doom 2016 it is not about being conservative and staying out of harm’s way to preserve health, it is about being proactive and aggressive in order to gain health and that makes all the difference. In this sense the 2016 version (well, sequel actually) builds meaningfully on the original by adding (double) jumping and mantling mechanics and glory kills are an essential addition in terms of keeping momentum. Now, of course, at high level of play, this is not true, it is in fact the opposite, the speed and challenge runners on Youtube have demonstrated that you can finish the game without being hurt and that avoiding enemy fire and not relying on glory kills is the way to great victory (not to mention justice). But at “normal” levels of play, I’d say that glory kills are essential in keeping the pace of the game so high.