The article below represents months of work and appears in Well Played 2.0, a game studies textbook published by Carnegie-Mellon University under the guidance of Professor (and Celebrity Guest Editor) Drew Davidson.

Each chapter of Well Played discusses a single game or franchise, with both meanings of the well-played phrase in mind: the game must be well played as a book is well-read, and it must provide something to better the medium as a whole. Beyond that, the analytical expectations are dependent on the writer. My chapter was about the STALKER franchise, which I know and love well.

I really wanted to do a “director’s cut” version of the article for Tap, including self-made, narrated gameplay videos and the like, but a recent computer crash has eaten up all my STALKER saves. It’d just take too much time to put a project like that together. Instead please accept the odd embedded YouTube video, plus some additional pix and multimedia that don’t appear in the book.

This is a textbook chapter, not a blog post. As such it’s even longer, boringer, and more pedantic than I usually write. It even has footnotes. Enjoy!

Alone for All Seasons

Environmental Estrangement in S.T.A.L.K.E.R.

Originally Published in Well Played 2.0: Further Reflections on Games and Meaning

Edited by Drew Davidson, Ph.D

Etc. Press, Carnegie-Mellon University

CNPP Reactor Four after the accident.

The explosion shattered a quiet, cool April night in Ukraine, ripping through the housing that concealed the uranium and graphite pile of Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant’s Reactor Four. The men in the control room had known of a problem for a few moments, but their frantic attempts to bring it under control had failed. Flaws in the design reduced the flow of cold water into the reactor during a safety test, allowing it to boil its reserves of liquid coolant. A 2,000 ton steel-reinforced concrete roof was no match for the explosively expanding vapor. It ripped the lid off the reactor as easily as a frustrated child losing a game might flip a checkerboard, catapulting the entire assembly 400 feet into the sky. Searing steam rushed out, replaced by crisp spring air. With a sudden abundance of oxygen to burn, the graphite in the reactor pile erupted into flames. The uranium fuel rods melted into molten slag as the blazing fire hurled nightward a black column of radioactive soot. And so began, at 1:23 a.m., on April 26, 1986, the greatest radiological disaster in the history of humankind.

“Close the window and go back to sleep,” Vasily Ignatenko told his wife. “I’ll be back soon.” He was a firefighter on duty in the nearby city of Pripyat. Along with his colleagues, Ignatenko was among the first emergency crews to respond to the explosion. All they knew was that there was a fire at the power plant.

Of her husband’s brief hospitalization in Moscow, Lyudmilla Ignatenko would say, “pieces of his lungs, pieces of his liver, were coming out his mouth. He was choking on his internal organs. I’d wrap my hand in a bandage and put it in his mouth, take out all that stuff.”

Vasily Ignatenko died less than a month after the Chernobyl incident. No first responders would survive the year. No one warned them the fire was radioactive. No safety equipment was issued. No Geiger counters were available. In their hurry to help, many of Ignatenko’s squadmates had arrived in shirtsleeves, without even their firefighter’s gear for protection.[i]

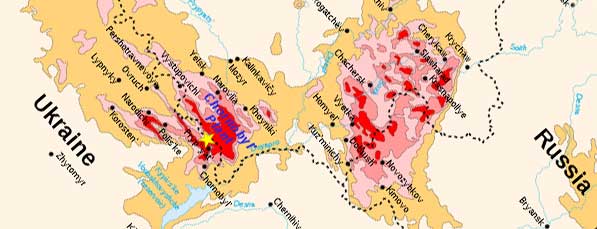

Within four months, the entire city of Pripyat, population 50,000, and dozens of surrounding towns and villages had been evacuated. In total, 30 square kilometers around the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant’s doomed Reactor Four were emptied and sealed off. Considered more toxic than anywhere else on the planet, the forbidden region is known as Чорнобильська зона: the Zone of Exclusion.[ii]

The Zone of Exclusion.

21 years later that Zone, so removed from the world we live in, would help catalyze a game design technique with the power to shepherd players to expansive new realms of immersion.

Into the Breach

In 2001, Ukrainian developer GSC Game World announced S.T.A.L.K.E.R.: Shadow of Chernobyl. Originally titled Oblivion Lost, GSC envisioned an open-world science fiction shooter set in an alternative Exclusion Zone – in which a second explosion at the reactor greatly expanded the size and personality of the Zone, and altered reality in the region. It allowed the power plant itself to become sentient: an alien, incomprehensible intelligence that would come to be known as the C-Consciousness. And what is a brain without a body? The Zone itself would fill that role.

Another result of this event was the appearance of “anomalies,” pockets of roaming, reality-bending energy. Anomalies can misdirect time, invert gravity, emit bursts of heat or electricity, even teleport matter. Many are almost invisible, and human contact with nearly every kind causes extreme injury or death. Anomalies, in addition to scattered radiation and the sudden appearance of ferocious mutants, meant traversing the Zone of S.T.A.L.K.E.R. would be a hazard in and of itself.

However, that danger comes paired with irresistible temptation. Anomalies “throw” objects with fantastic, impossible physical properties, artifacts that violate all known laws of physics. Many are deadly or highly radioactive, and all are precious. Soon a black market trade springs up, as scientists and collectors offer massive bounties for the bizarre items. Collecting them requires putting oneself in incredible peril, but the prizes are worth it. Heavily armed treasure hunters swarm to the Zone, braving its many dangers in a radioactive gold rush. Even the military cannot stop the flood, whose lust for adventure and wealth drive them to the poisoned realm.

Those who come to this violated region face unbelievable hardships. The Exclusion Zone has always been guarded by the military, but when precious objects are discovered, the cordon is tightened. Soldiers have strict shoot-to-kill orders; horrifying mutants dominate the countryside; while radiation pockets and anomalies promise hideous death to the careless. Deeper in the Zone are eerie, haunted territories and unexplained psychic assaults. None of it prevents dangerous, profit-minded adventurers from coming in. But of course the greatest danger to visitors is each other – society’s leavings, its unwanted. Men who come to be known as Stalkers, a nod to Andrei Tarkovsky’s eponymous film, itself a rendering of the classic Russian science fiction novel Roadside Picnic.

S.T.A.L.K.E.R. put players in the boots of men who sought wealth in a new and deadly wild world, one different from the Yukon or the old west – those places, after all, belong here. The Zone does not. Spawned from a terrible violation, the game envisioned it as an unnatural, unknowable place, beyond true comprehension, one that is inherently not of Earth – maybe even not of this universe – and certainly not for human beings. Soon enough a legend begins: tales of a final artifact, said to lurk deep inside the ruins of the power plant. According to rumor, any Stalker bold or foolish enough to brave that contaminated landscape and penetrate the concrete sarcophagus that entombs Reactor Four would find inside a power to grant all his wishes.

As the myth of the Wish Granter spread, the Zone became home to more and more of these prospectors. GSC Game World’s reinvention of the Zone draws the cruel, the violent, the avaricious, the hungry for adventure… and those who belong nowhere else.

“There was no place for me in that world,” one Stalker confides, referring not to the world of the Zone but to ours. “It didn’t want me.”

The Garbage - a dump for irradiated cleanup equipment abandoned in the disaster.

The World Ends with You

Pre-release press was enthusiastic, but as development dragged on and target release dates were missed again and again, industry watchers grew ever more cautious. Nevertheless, when Shadow of Chernobyl was finally released in March of 2007, it received widely favorable reviews[iii] despite significant bugs, poor optimization, and often-incomprehensible translation. General consensus was that for all of its shortcomings, Shadow of Chernobyl transcended them. Its boldness and innovation dwarfed the faults in execution.

Despite the rough edges, the S.T.A.L.K.E.R. series will be remembered as among the most groundbreaking and forward thinking games of the decade. Years before designers Cliff Bleszinski and Harvey Smith agreed that “the future of shooters is RPGs,”[iv] S.T.A.L.K.E.R. stood alongside Deus Ex and System Shock to set the stage and demonstrate the wisdom of that remark.

To my mind, S.T.A.L.K.E.R.’s most fascinating trait is its use of a technique I call environmental estrangement: a tool that allows developers to imbue games with a wider and subtler spectrum of emotions and an intensely powerful, intensely personal sense of immersion. While all games can evoke emotion and immersion, environmental estrangement virtually requires players to develop a much more acute connection to the game world, making the experience more intense and nuanced.

The desolate Yantar Lake region, home to Stalkers turned into zombies by radiation, to heavily bunkered scientists, and to some of the darkest secrets in the Zone

Let’s be honest: games are not famous for their ability to evoke complex feelings. Simple ones, no problem. But the more subtle a feeling is, the harder time a game has making the player feel it. Sadness? Yes. Melancholy? No. Anger? Sure. Resentment? Probably not.

I believe environmental estrangement techniques can rectify that. Though the name “environmental estrangement” and the theory under discussion are my own, when used in commercial games like S.T.A.L.K.E.R., they make the player feel something much more strongly than most games can. This is accomplished by effectively divorcing the player from his or her own world and sense of self. The human player is taken out of the “real world” environment and placed into the world of the game. A player in this state is easy for designers to manipulate.

Environmental estrangement is about making you feel something; in the case of S.T.A.L.K.E.R., you feel a place – the Zone – on a very instinctive level. It builds an emotional connection with the game world, using a variety of experiences to create a persistent sense of forlorn detachment, a profound loneliness, an intense, solitary immersion so powerful that the player must experience the Zone in a deeply personal way.

In a nutshell, S.T.A.L.K.E.R. uses environmental estrangement to snatch you from this world and put you into another one: one that is unwelcoming, unknowable; obscene. Yet despite this it also creates a need to be in that world, for all that you are unwanted. The player becomes part of the territory, not despite but because of the bleak, depressing emptiness of S.T.A.L.K.E.R.’s Exclusion Zone, the unnatural, ghostly quality that evokes a feeling that you’re an uninvited visitor in a haunted and unreal place.

It is best to befriend or avoid anyone packing this level of protection.

S.T.A.L.K.E.R. is not the only game I have observed that uses environmental estrangement, nor is the technique limited to making the player feel lonely. A little later on we’ll briefly discuss some other examples of games that use the same techniques to evoke different but equally subtle sensations. By divorcing the player from any preconceptions of a world, environmental estrangement grants developers a wealth of delicate tools with which to directly manipulate the player in complex and uncommon ways. I will discuss the S.T.A.L.K.E.R. games in the context of environmental estrangement, reviewing the narrative, experience, setting, and mood as foundations for how the technique can affect the player.

Please note that the following contains story spoilers that may impact a newcomer’s experience with the games. At this writing, the S.T.A.L.K.E.R. series consists of three titles: Shadow of Chernobyl (2007), its prequel Clear Sky (2008), and Call of Pripyat (2010). In general, when I refer to S.T.A.L.K.E.R., I mean the series as a whole; I employ installment subtitles to describe them individually. Some additional differentiations are also necessary:

- S.T.A.L.K.E.R. (in italics) refers to the game franchise

- S.T.A.L.K.E.R. is a narrative macguffin within it

- Stalker is the Tarkovsky film

- Stalkers are the individuals who prowl the Zone for riches and adventure

Finally, my experience with the series is limited to the North American localization of this Ukrainian title.

Where the Wild Things Are

It is difficult to clearly explain the narrative arc of S.T.A.L.K.E.R. The games jump around in time and often contradict one another. No one path can be considered canon, as the Zone’s ability to alter time, space, and reality interferes with a linear storyline: characters that had been dead reappear, events that had been prevented nonetheless occur. But the story, however difficult to follow, is important.

Shadow of Chenobyl opens with a truck hauling a load of rotting corpses out of the Zone. Rain spatters the windshield as the Soviet-era vehicle trundles through a late-night rainstorm. Seconds into the opening cutscene, a lightning strike flips the truck headlong into a ravine, scattering its gory cargo through the canvas flap before exploding in flames.

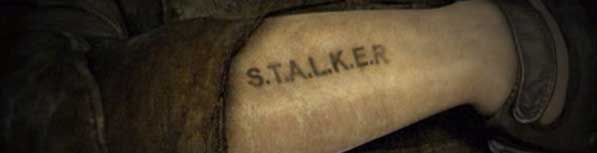

Hours later, as dawn breaks, a Stalker crests the ravine at a run, proceeding downward to examine the wreckage and loot bodies for valuables. He is surprised to discover that one of the people from the back of the truck is alive, unconscious, and bearing a peculiar tattoo – S.T.A.L.K.E.R. – on his wrist. “At least death would have saved him from the dreams,” muses this nameless arrival. He scoops the unconscious man up and trots off through the landscape, and thus you enter the game injured, penniless, and out cold.

Already in this opening cinematic, we see environmental estrangement at play: a bleak and grim landscape, a transport for the dead, a heavily armed loner picking through wreckage for items of value. Solitude, death, and greed: key ingredients in S.T.A.L.K.E.R.’s soup.

That loner takes you to Sidorovich, a merchant who trades equipment, artifacts, and information with local Stalkers and clients from outside the Zone. Entrenched in a concrete bunker, Sidorovich always seems to know the latest news, and he is very interested in men with the S.T.A.L.K.E.R. tattoo. Though no one knows what it means, it only appears on Stalkers who have ventured deep into the Zone, an area so dangerous most consider it impenetrable. Those who go too far are usually killed by radiation, eaten by monstrous mutants, or shot by Monolith troopers – a psychotically religious faction of former Stalkers who worship the Zone, somehow trading their minds for the ability to survive in heavily irradiated areas.

A Stalker interrupts Sidorovich during lunch to deliver the body of the Marked One.

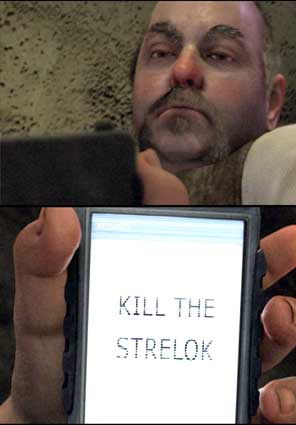

Stalkers who avoid the radiation, mutants, and Monolith still die; an energy field of some sort literally boils their brains. Sidorovich and a loose association of other black marketeers recognize that the region beyond this “Brain Scorcher” would be virgin artifact territory, a fortune for the first to get there. Near the Zone’s heart lies the abandoned city of Pripyat, promising more riches; and beyond that the power plant, supposedly the home of the Wish Granter. Sidorovich has seen the S.T.A.L.K.E.R. brand before, but never on someone who is still alive. As he rummages through your clothing, he comes upon a PDA with a single to-do item: KILL THE STRELOK. At that moment you awaken, snatching the PDA from his hand.

The Marked One, as Sidorovich names you, cannot remember anything that happened to him before the accident. While amnesia in videogames is a common and ridiculed trope, it proves helpful here in order to conceal some key plot points, in particular who “the” Strelok is, and why the Marked One is supposed to kill him. The amnesia creates an empty vessel, reducing the importance of his character. Indeed, the real “protagonist” of S.T.A.L.K.E.R. is the Zone itself. If characters in narrative are primarily responsible for the evocation of emotional response, and assuming that a character can be anything[v], then certainly a place can take center stage as easily as a person. The Zone is the star of this show.

S.T.A.L.K.E.R. was disorienting to many gamers, who by 2007 had developed certain expectations for how first person shooters were to be played. Traditional shooters typically offer one path, or at most a few; these are often recursive so it’s impossible to really get lost. The environment itself is usually little more than a backdrop designed to showcase set-piece occurrences such as battles or puzzles, and in most cases players never return to areas they have visited. Even the most beloved first person games – Thief: the Dark Project and Half Life 2, for example – essentially herd the player in one direction, through predetermined missions and carefully crafted level design. S.T.A.L.K.E.R. is nothing like that.

S.T.A.L.K.E.R. was disorienting to many gamers, who by 2007 had developed certain expectations for how first person shooters were to be played. Traditional shooters typically offer one path, or at most a few; these are often recursive so it’s impossible to really get lost. The environment itself is usually little more than a backdrop designed to showcase set-piece occurrences such as battles or puzzles, and in most cases players never return to areas they have visited. Even the most beloved first person games – Thief: the Dark Project and Half Life 2, for example – essentially herd the player in one direction, through predetermined missions and carefully crafted level design. S.T.A.L.K.E.R. is nothing like that.

When you leave Sidorovich’s bunker, you can go anywhere. Eventually hills or fencing or radiation or the ever-present military will cut you off, but there are no corridors here. The vast majority of S.T.A.L.K.E.R. takes place outdoors, with all the freedom thereof. This too is part of the effect that S.T.A.L.K.E.R. has on most players: here at the outset, in Shadow of Chernobyl, you are unarmed, without friends or contacts, in a dangerous countryside, with just the vaguest idea of where to go or what to do once you get there. “Kill the Strelok” is the only guidance you’ve got, and while Sidorovich reveals that there is a Stalker by that name, no one seems to know where he might be or why you’d want him dead. From this moment forward, one word will define your time in the Zone: aloneness. Even in the company of other Stalkers, the persistent sensation of forlorn solitude dominates the experience. That sense of aloneness, of desolation and isolation caused by your surroundings, is environmental estrangement at its best: use of the game environment and tropes within it to affect your mindset as a player and subtract you from your conscious awareness of real-world surroundings.

The Zone maintains a viselike hold, not only on the Marked One, but on all Stalkers. “God knows how long I’ve spent here,” sighs Wolf, a friendly Stalker early in the game. “But it’s like this place doesn’t want to let me go.”

About halfway through Shadow of Chernobyl the player learns that Strelok and the Marked One are the same person; you are the man you are trying to kill. Strelok was obsessed with the Wish Granter, a mania that drove him to sacrifice anything to reach it and tame the power it promised. He had made great progress toward that goal, until he was struck with amnesia and forced to essentially start his quest again. But he fails to realize that the Zone is not simply a place. It is a thing – a living thing – that knows what Strelok is up to, and despises him for it.

Electrical anomalies are easy to spot, but among the most dangerous.

That Strelok is alive at all was an error on the part of the C-Consciousness, the sentient entity spawned from Soviet-era experiments in mind control. It occupies the power plant and a network of secret laboratories; it is the mind and the Zone is its body. It brainwashes or kills anyone who comes close to discovering it, marking the corpses as S.T.A.L.K.E.R.s – scavengers, trespassers, adventurers, loners, killers, explorers, and robbers. The tattoo is a scarlet letter left behind on unwelcome intruders as a warning to the others. The brainwashed are programmed to perform tasks of its choosing. The C-Consciousness seized Strelok moments before Shadow of Chernobyl began. Not realizing who he was, it wiped his mind and sent him off to kill… Strelok, a Stalker it knew was on the verge of discovering it. And as something alien and unknowable, it does not think of humans as equal entities – just as we would say “kill the mouse,” so the C-Consciousness wants to kill the nuisance. The game’s seven endings, based on decisions the player has made throughout, dictate Strelok’s fate.

The subsequent Clear Sky and Call of Pripyat are of great value for understanding the Zone as a character and the nature of the Stalkers who live there. Clear Sky is set a year before the events in Shadow of Chernobyl – well after the 1986 meltdown and GSC’s subsequent fiction, but before the C-Consciousness has set up the Brain Scorcher to protect itself. Your character in Clear Sky is a mercenary Stalker named Scar. Injured at the beginning of the game, he is rescued by the mysterious Clear Sky organization, a scientific team dedicated to study of the Zone. The group believes that recent occurrences in the Zone have been caused by the region reacting to a perceived threat – which we know to be Strelok’s pre-amnesia exploits as he and his allies attempt to reach the power plant.

The Zone can and does protect itself. Aside from the Brain Scorcher field, its primary defense mechanism is a blowout, or emission – a colossal radiation storm originating from the power plant. Blowouts are terrifying events; the sky bruises, the air itself turns angry scarlet as the earth shakes and thunder rumbles. They are deadly, driving animals before them, killing anyone and anything that cannot find shelter. Minor blowouts can be daily events, but massive ones have a sinister purpose. With each major emission, the Zone changes. Routes that had once been safe become irradiated, dangerous paths open up, anomalies move around and throw new artifacts. Clear Sky has learned that Zone is getting larger with each serious blowout. The organization believes that coexistence with the Zone may be possible, but that behavior like Strelok’s is antagonizing it and threatening the possibility that something as alien and unnatural as the Zone will tolerate humanity. Strelok’s invasion has caused instability. All that matters to him is reaching the Zone’s toxic beating heart, the ruins of the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant. The Wish Granter, and the power it promises, drives him ever forward, so forward he goes, ignoring the ruin he leaves in his wake. Like an immune system responding to a virus, the Zone is defending itself.

Environmental estrangement allows GSC Game World to separate the player from normal reality and immerse him or her in the Zone. The Zone is portrayed as an incomprehensible entity, completely beyond human capability to understand or manage. The Clear Sky organization’s goal – coexistence – may be the only realistic solution for the presence of the Zone in this world, and may also be fueled by the revelation in Call of Pripyat that much of Clear Sky’s leadership was once involved in the research that led to the appearance of the C-Consciousness in the first place. But coexisting with something so alien, particularly when provoked by Strelok’s actions, becomes impossible. At the prequel’s climax, the organization’s philosophy of coexistence leads to the utter ruin of Clear Sky and the death of everyone involved with its activities. Strelok’s view – that the Zone is a treasure to be dominated and controlled – threatens to destroy him and reshape the Zone completely; creating the world we visit in Call of Pripyat.

Most critics consider Clear Sky a disappointment compared to its predecessor,[vi] but the environmental estrangement remains effective, evoking that eerie loneliness in the player, despite Clear Sky’s intense focus on interaction with other Stalkers. This prequel’s Zone has many more people, and your character works with them regularly. The revelation of Clear Sky is its presentation of the Zone as a malicious living thing, yet one that people willingly seek out, and become attached to once there. Moreover, it shows the pointlessness of existence in the Zone, as faction wars drag on and corpses pile up. More than once the player must watch friends fall and bullets fly as Stalkers fight over petty philosophy or territorial squabbles. Nothing here matters, everything is poisoned; it’s all worthless. And thanks to the potency of environmental estrangement, the player is able to easily feel this complex, layered emotional connection to the issues of the game. Those “precious” artifacts Stalkers risk everything to collect are so dangerous that even carrying one around can result in a lethal dose of radiation. The bleak, empty landscape highlights the heartlessness and cruelty of life in the Zone, where men kill each other as though this crumbling building or that derelict factory were strategically worthwhile.

Clear Sky took us back a year, and set up the events in Shadow of Chernobyl. Call of Pripyat, meanwhile, tells the story of what happened in the Zone just moments after the first game ended. At the climax of Shadow of Chernobyl, the player had disabled the Brain Scorcher, eliminating the barrier that kept Stalkers from getting too close to the power plant. With the Scorcher offline and promise of the Wish Granter beckoning, the race is on: hundreds of Stalkers pour into Pripyat, each intent on reaching the ultimate treasure first. Warring factions, Monolith’s zealots, personal enmities, and individual avarice reduce the city to a lunatic war zone. Outside the power plant itself, the running gun battle becomes even more chaotic. The Ukrainian military has seized this sudden concentration of Stalkers as an opportunity to kill as many of them as it can, and so dispatches dozens of heavy attack helicopters and tanks. For its part, the C-Consciousness emits a colossal blowout that completely reshapes the Zone.

Where Clear Sky had the player exploring the same general areas of the Zone, Call of Pripyat features three completely new regions, which had been inaccessible until the latest emission. Stalkers waste no time moving in and setting up new camps. In this third installment, you play a Major in the Ukrainian military who agrees to go undercover as a Stalker to learn the fate of five attack helicopters that went down during the climactic moments of Shadow of Chernobyl.

Major Alexander Degtyarev, the protagonist of Call of Pripyat, with his gang.

Call of Pripyat takes advantage of new technologies and lessons learned from earlier games to further refine the Zone’s inherent desolation and loneliness. Early-morning trudges through misty fens, nighttime mutant hunts, encounters in the rusted hulks of beached freighters abandoned in 1986 disaster make Call of Pripyat a more introspective game than its predecessors. The player explores abandoned villages and haunted caverns; the eerie ruins of Jupiter Station, a massive radio factory; and finally Pripyat itself, visited only briefly in Shadow of Chernobyl. The evolution of the S.T.A.L.K.E.R. games is clear in Call of Pripyat, in which GSC Game World was finally able to implement mechanics that had long been intended: the game’s remarkable artificial intelligence, moving anomalies, and blowout-fueled changes to the world as a whole.

Slower-paced, Call of Pripyat is a meditative experience. It retains Clear Sky’s rumination on violence and aggression, while all three games make a concerted effort to exclude any sense of comfort or security. Throughout all three games, diegetic sound is key to this: the loneliness of a wind gust, the far-off bark of a dog, the whale-sounding call of loons deep in the Zone, all make you relish and suffer the loneliness created by the game. But efforts to exclude the player from any sense of home or comfort do not end there.

GSC Game World was hardly unaware of the bleakness of the world it created, and maximized its impact with every sensation. Much of S.T.A.L.K.E.R.’s soundtrack was created for the game by Ukrainian death metal band Firelake, of which GSC Game World marketing director Oleg Yavorsky is a founding member. But in a departure from the roar-intensive shriekery of traditional rhythmic death metal, Firelake demonstrated its versatility, producing lonely flute and string numbers, lingering ballads, and environmental tones designed explicitly to evoke emotional response. Consider some lyrics from the series theme song Dirge for the Planet, a hauntingly apocalyptic composition that speaks, perhaps, of a world entirely engulfed by the Zone[vii]:

The seas overdumped

the rivers are dead

all planet’s cities turned a deserted land

annihilation declares its day […]

Dancing on the ashes of the world,

I behold the stars

heavy gale is blowing to my face

rising up the dust.

Barren lands are desperate to blossom

dark stars strive to shine

still remember the blue ocean

in this dying world

Throughout the evolution of the series, even as GSC has experimented with new mechanics, new interfaces, and updated play styles, the developer’s vision of the Zone has never changed.

It all comes down to the Zone. The Zone produces these artifacts that Stalkers fight and die for, and the Zone, by its very existence, provides a haven for violent men to do violence. A player willing to give himself wholly over to the world of the Zone will experience this environmental estrangement on a very conscious level, as everything in the S.T.A.L.K.E.R. games is designed to remind players how alone they are.

A shattered motorway bridge in the Zaton Swamps, used by military scientists until an anomaly destroyed it. As you might imagine, you have to go down there.

The storyline, characters, and even music of the S.T.A.L.K.E.R. series adeptly connects the player to the environment by removing him from reality, enhancing the feel of the world. This structure allows the series to comment on specific themes. Overall the morality tale of S.T.A.L.K.E.R. is a commentary on greed, on incomprehensible entities, on connections men form with places. By linking the player to the land as effectively as the Stalkers themselves are tied to the Zone, GSC creates a world and a fiction that, however circuitous, does help the player feel for the people, the place, and even the C-Consciousness, to whatever degree a person is able to empathize with something so decidedly alien.

We have seen how the storyline, characters, and even songs can act as tools of environmental estrangement to closely control player immersion; let’s now look at the manipulation of two other key elements: setting and mood.

Magnificent Desolation

The very word “Chernobyl” evokes an emotional response in most people. It remains contaminated to this day; during the desperate weeks immediately after the explosion, radiation from the fire reached nearly every point on the globe. Soviet-era secrecy caused misconceptions about the scope and seriousness of the disaster, with no agreed-upon findings of deaths or long-term effects. The official Soviet tally is 56 dead.[viii]

Aerial view of the Wormwood Forest near CNPP. It was renamed the Red (or Magic) Forest because of the ginger color of the trees killed by the fire, and the soft glow emitted by their trunks during the early days of the disaster.

Meanwhile, a Greenpeace study claims 258 within a few weeks, 4,000 by year’s end, 93,000 by 2006, and more than 140,000 all told.[ix] Those numbers are far from the most pessimistic: recently three Russian scientists published an exhaustive report based on hundreds of sources, claiming that 985,000 have already died.[x] The truth is no one knows. No one can know. How many has Chernobyl killed? Impossible to say, because Chernobyl is still killing. It will continue to kill for generations, as mothers and fathers pass tainted genes on to their offspring. As such it has taken on an unholy significance with some, a specter of nuclear dangers not fully understood.

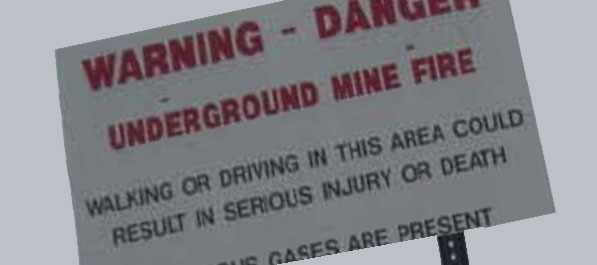

Today, the Exclusion Zone is safe to visit, to a point. An unknown number of people live there, having either returned home after the evacuation or never left in the first place. Still, it is reasonable to remark that the area is largely abandoned and will remain so for a century or more. Chernobyl is the Eastern European version of Centralia, Pennsylvania, the nearly deserted town under which a coal fire has raged since 1962[xi]. A handful of people remain there as well, intentionally cut off from the world. No post, power, telephone, not even a ZIP code remains to identify Centralia. Settings such as these – derelict, forgotten, cast off, haunted by history and abandoned by most, are ideal fodder for game worlds in which the environment itself is an emotional affecter.

Theoretically speaking, developers could apply environmental estrangement techniques to any location. Bearing in mind that the objective of the technique is to make the player feel something at a primal level by first removing them from their present environment, making it work is simply a matter of creating an immersive experience. In the case of S.T.A.L.K.E.R., a great deal of firsthand research allowed GSC’s worldcrafters to sample the flavor of the real Zone and transmit it into their game. For Kiev-based GSC Game World, it was an easy matter to visit the Exclusion Zone. Many landmarks and geographical features that appear in the game mirror real-world locations. The poisoned realm of Chernobyl is an actual place, a place the developers went to great effort to model in their game. In accomplishing this, they were able to transplant the much-lauded feeling of loneliness that exists in the real Exclusion Zone. Visitors have described the eerieness of the region[xii], sometimes speaking at length about how they felt disconnected from the rest of the world while there. Capturing this sensation in a digital medium is not easy, but the results when successful are striking.

As it happens, S.T.A.L.K.E.R. removes the player from his or her own world and places them in one permeated by the sensation of melancholic loneliness. One of its most impressive achievements is that it makes the player feel alone (and lonely) regardless of actual company. S.T.A.L.K.E.R.’s world is not overrun with people, but it is reasonably crowded. The Zone is not so large that the player will go hours without seeing another person. Later segments of all three games are downright bustling. The madness in Pripyat and outside the power plant in Shadow of Chernobyl are nothing short of chaotically populated, with hundreds of Stalkers, soldiers, and Monolith fighters exchanging gunfire. But the sense of loneliness endures.

Mad World

Hand in hand with setting is mood. Where you are is important, but the critical key to making environmental estrangement work is how the place makes you feel. In S.T.A.L.K.E.R., it makes you feel lonely (other games use environmental estrangement to create different sensations, which we will discuss later). Chernobyl, empty and legendary, is a natural setting for a game, particularly a lonely one. It might seem that with so much history surrounding the place, environmental estrangement would be part and parcel of the experience, but Chernobyl alone is not enough. Call of Duty 4: Modern Warfare and Modern Warfare 2[xiii] both feature missions set in the Exclusion Zone, but the sensation of the place is very different than that in the S.T.A.L.K.E.R. games. It feels much more like a traditional action setting, with only the crumbling buildings and occasional landmarks to distinguish it from any other generic location. In a game world, atmosphere dictates player state of mind.

The Boiler Anomaly from Call of Pripyat. By the third game, certain anomalies, like this one, have become geographical landmarks, rather than roving deathtraps.

From the moment you take control in S.T.A.L.K.E.R., the game’s vision of the Zone bombards you with visual, auditory, and experiential cues designed to separate you from the world of the present. Leaving the ramshackle encampment where rookie Stalkers gather their courage before venturing out into the Zone’s dangers in Shadow of Chernobyl, you crest a hill and encounter your first anomaly. It’s nothing more than a localized distortion, about the size of a phone booth, nearly invisible, just a sort of… wiggle in the air. It is the middle of the day as you stand on a pitted asphalt street. Though the Newbie Camp of 20 or so souls sits less than a football field’s distance behind, there, just over the next ridge, looms the Zone in all of its unearthly and terrible beauty. Any player who stands on that rise cannot escape the shivering sense that they are suddenly and truly on their own.

Sometimes the smallest things in S.T.A.L.K.E.R. evoke the strongest reaction. Every now and then a breeze whispers by, carrying leafy flotsam and dust. Odd as it may seem, that puff of wind alone is sufficient to make many players shudder with loneliness. A rainstorm soaks a group of Stalkers trudging through a swamp as the mournful yowl of a stray cat echoes nearby. Two rookies warm themselves around a trash fire, one strumming a tune on an acoustic guitar. Gnarled trees point like arthritic claws to the sky, their bases wreathed in mist. Crumbling homes speak of the lives hurriedly abandoned in the days after the disaster. In many areas of the Zone, derelict buildings serve as crude encampments or faction bases, while a labyrinth of irradiated and abandoned cleanup equipment – trucks, fire engines, backhoes, busses, even the odd helicopter – crouches next to mountains of half-buried steel rebar and concrete blocks. The ability of S.T.A.L.K.E.R. to so powerfully evoke these places helps demonstrate the effectiveness of environmental estrangement as a design technique that creates a sense of reality other approaches cannot achieve.

This allows the S.T.A.L.K.E.R. games to readily toy with player emotions, swapping terror, loneliness, melancholy, and exhilaration with ease. In Shadow of Chernobyl, for example, deep in the Zone you visit the ominous Red Forest region. It received the highest dose of radiation during the days after the disaster, when the reactor fire was still out of control. Radioactive particles settled on the spruce trees and killed them, turning the once-green forest ginger-red.[xiv] Red Forest is still one of the most heavily irradiated areas of the Exclusion Zone, and in Shadow of Chernobyl it is also the hidden location of the Brain Scorcher, the psychic field that kills Stalkers who venture too close to Pripyat. At first massive radiation and relentless assaults from Monolith troops bring a sense of white-knuckled action. As you draw nearer the vast electrical substation that houses the Scorcher, you experience brutally escalating psychic assaults. The air turns gold and noisy, while distorted, incorporeal creatures materialize and attack from all sides as the Marked One’s own mind turns against him. Inside the Scorcher complex itself you cannot help but expect the worst terrors, given the starts encountered outside. Instead, the entire facility is almost abandoned, forcing you to experience a good 35 minutes of agonizing tension, broken by only two or three encounters made all the more startling by their rarity. The instant you succeed in disabling the Scorcher, though, the military and Monolith troops pour in. What had been an empty tour becomes a blood-drenched race for the exit.

Nihilism by Design

What, then, is the value of environmental estrangement in game or level development? How can it be incorporated into game development’s creative grammar?

Author Stephen King once said, “Naturally, I’ll try to terrify you first, and if that doesn’t work, I’ll try to horrify you, and if I can’t make it there, I’ll try to gross you out.”[xv] Similarly, developers do well to have at their disposal a selection of tools to manipulate player immersion, overlapping them to create experiential chains. Environmental estrangement is such a tool, one with broad leveraging opportunity to affect the player in a variety of ways.

Ultimately it is a tool of immersion: in S.T.A.L.K.E.R. it creates a sense of place, which is then tuned to suit the needs of the game. It uses the dismal, melancholy setting across its entire media to accomplish this. But the value of environmental estrangement goes beyond simply creating forlorn, gloomy realms, and certainly beyond creating horror. It can even be used to create positive reactions. There is great beauty in S.T.A.L.K.E.R.’s ruined buildings, crumbling bridges, and rusted-out industrial parks, while the chaos in Pripyat and the running gun battle outside the power plant itself are nothing short of exhilarating. Savvy developers utilize environmental estrangement as a tool to further other creative goals of a game because players fully immersed in such universes are very easy to startle, excite, frighten, or thrill. S.T.A.L.K.E.R. is a dominant example of the technique, with some players returning again and again just to re-experience the atmosphere[xvi].

Environmental estrangement must permeate level design, art, story, scripting, audio, and graphics in order to work. As such the design team must share a creative wavelength to ensure consistency throughout all these game components, and the team must also understand the objective of the immersion they are creating. S.T.A.L.K.E.R. is about connecting one’s heart to the lonely, inhuman Zone. Other games use the same technique to accomplish completely different feelings of immersion.

The Void, by Ice-Pick Lodge

Russian developer Ice-Pick Lodge has employed environmental estrangement in the creepy eroticism of The Void (2009), a game that sets the player in a gloomy afterlife robbed of color. The Void has a hostile sexuality quite unique in games and realized through the application of environmental estrangement to “put” the player in that realm. The same studio also developed Pathologic (2005), a story about a diseased town with a dark and hideous secret. Pathologic’s release pre-dates that of S.T.A.L.K.E.R., and may have influenced the latter’s approach. In the case of Pathologic, Ice-Pick Lodge employed environmental estrangement techniques to adeptly evoke revulsion in the player, a creeping, skin-crawling horror at first unidentifiable and later overwhelming.

Action Forms, Ltd., another Kiev-based developer, accomplished it in the underappreciated Cryostasis: Sleep of Reason (2009), set in a haunted Soviet nuclear icebreaker, where the frigid temperatures are the true enemy. S.T.A.L.K.E.R. uses environmental estrangement to make you feel the solitude; Cryostasis uses it to make you feel the cold.

Polish studio People Can Fly garnered very positive press with Painkiller (2004), a high-action arena shooter with singularly brilliant art direction in its presentation of life after death, visually painting a world in which every player found themselves questioning their own preconceptions of what hell would really be like.

Meanwhile, 4A Games, also based in Kiev, manages with Metro 2033, a corridor shooter based on the social commentary-rich science fiction novel by Dmitry Glukhovsky. This game has garnered many comparisons to S.T.A.L.K.E.R., but in truth its use of environmental estrangement is much more about creating sympathy for the desperation of the human condition than about any connection with a place.

Painkiller.

So far, we have seen environmental estrangement in games that generally share two key features: a bleakness of philosophy, and nativity in Eastern Europe, particularly the former Soviet republics. Whether eastern Europeans are naturally more adept at producing hopeless environments is unclear, but there is no doubt that some of the most dismal and melancholy game settings have originated in that region. However, at this point we do not yet see it widely applied in games elsewhere, though there is no reason why the technique should be limited to work from that area, or limited to “dismal and melancholy game settings.” Perhaps other developers have not yet fully realized its potency as a tool. With the ongoing success of S.T.A.L.K.E.R. and the growing perception of eastern Europe as a powerhouse of unique creativity in game development, we may yet see environmental estrangement grow beyond these borders.

For now, though, many Western or Japanese games may be dark, gritty, or grim, but they are almost never disconsolate in the way that eastern European games often are. Even comparable settings are presented differently. Consider Bethesda’s Fallout 3 (2009)[xvii], a game with similarly apocalyptic overtones to S.T.A.L.K.E.R., set in a Washington, D.C. shattered by nuclear war. While the devastation in Fallout 3 is very ably presented, the emotional experience of exploring that wasteland is not at all the same as the experience in S.T.A.L.K.E.R. Journalist Shawn Elliott summed S.T.A.L.K.E.R. up quite succinctly: “Americans just don’t design shooters this way.”[xviii]

Inspiration and Influence

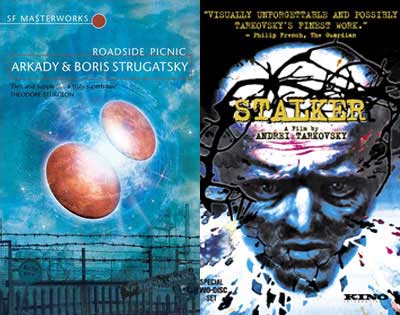

In an environment where games are almost never based on literature, S.T.A.L.K.E.R. also innovates. Roadside Picnic,[xix] the 1972 novella by Boris and Arkady Strugatsky, is the driving influence behind the game. In that story, aliens visited the earth and then left, abandoning some of their outrageously superior technology in areas scattered around the world. Called Zones, these regions were littered with bizarre anomalies that affected the space-time continuum and, like the anomalies in S.T.A.L.K.E.R., were typically deadly to humans. Of course, treasure hunters and scientists (called Stalkers; Roadside Picnic pioneered that title) risked life and limb to collect the advanced alien artifacts. One in particular, a golden sphere, supposedly held the power to grant the wishes of its finder.

In an environment where games are almost never based on literature, S.T.A.L.K.E.R. also innovates. Roadside Picnic,[xix] the 1972 novella by Boris and Arkady Strugatsky, is the driving influence behind the game. In that story, aliens visited the earth and then left, abandoning some of their outrageously superior technology in areas scattered around the world. Called Zones, these regions were littered with bizarre anomalies that affected the space-time continuum and, like the anomalies in S.T.A.L.K.E.R., were typically deadly to humans. Of course, treasure hunters and scientists (called Stalkers; Roadside Picnic pioneered that title) risked life and limb to collect the advanced alien artifacts. One in particular, a golden sphere, supposedly held the power to grant the wishes of its finder.

The title of the novel is a reference to the relationship between forms of life at different levels of civilization and intelligence. When we stop for a picnic, lower creatures have no conception of our activities. We are absurdly more advanced. Our most basic actions and tools are incomprehensible. They do not understand what we are doing or why we are there, they just know they want our sandwiches and potato salad. And when we go, sometimes we leave artifacts from our picnic behind: discarded plastic wrap, an empty soda can, a melting ice cube. All these things, so simple to us (indeed, worthless and disposable) are alien and terrifying to the animals. As they creep in to collect our scraps, they are entering a zone of terrible danger, where an unrecognizable object could mean fabulous riches or instant death. They know it is dangerous, but they cannot resist the temptation… as the Stalkers of Roadside Picnic cannot resist the temptation of discarded treasures from this alien civilization, one so advanced that we are to them as mice and ants are to us, so advanced they may have never noticed our presence on earth at all. Post-picnic scavengers are, to humans, as humans are to God – or, at least, as we are to entities so far advanced they might as well be God.

Russian filmmaker Andrei Tarkovsky directed Stalker (1979) [xx], based on Roadside Picnic, and with a script co-written by the Strugatskys. Produced well before the Chernobyl incident, Stalker is a beautiful and melodic film, and intentionally far more nebulous regarding the Zone and its dangers than the novel on which it is based. Since access to the Zone is supposedly illegal, early on the characters agree to use anonymous titles rather than names. Thus the leads are Stalker, Professor, and Writer, the former making a living by guiding people into the region. The rumor about the power to grant wishes remains the same. In the film, instead of a golden sphere, it is simply a room, a room that Stalker insists must never be approached directly. He claims that death lurks invisibly in every inch of the Zone, and that without him Professor and Writer would be killed in minutes. Stalker’s incessant warnings and elaborate precautions frighten the others at first, but over time Writer and Professor come to doubt that the Zone is dangerous at all.

Indeed, the trio arrive at the room without injury, and here Professor reveals that he has brought along a small nuclear bomb to destroy the Zone, to prevent evil men from using the room to take power.

“I wouldn’t bring anyone like that here,” Stalker cries, desperate to prevent the destruction. He needs his Zone as much as the Stalkers of the game need theirs, and the idea of its destruction is unthinkable.

“You are not the only Stalker in the world, my friend,” replies Professor, though in the end he decides against destroying the room.

S.T.A.L.K.E.R. draws more inspiration from novel than film, and naturally takes significant liberties in the interest of making the game fun. The concept of the Zone as a place to which some men are irrevocably drawn, despite the dangers and in search of an all-powerful artifact, resonates through all three installments. Whereas Professor was willing to destroy the room in order to prevent evil men from using it for their own ends, S.T.A.L.K.E.R.’s Wish Granter is its own self-correcting mechanism. In the game’s five “bad” endings, the player does in fact reach the Wish Granter and wishes for something based on prior in-game decisions – wealth, immortality, power, etc. In every instance the Wish Granter provides exactly what he asks, but in a way that either kills or cripples him. The Wish Granter exists to destroy the men who would use it.

The Power Plant - awake, aware, and angry.

On the subject of men, the absence of female characters in the S.T.A.L.K.E.R. games is worthy of note. While this may have simply been a convenience on the part of GSC Game World, it seems odd that a game in development for over six years would overlook something as obvious as this in the interest of simplicity. While the likely truth is that GSC could not be bothered to create the models and animations necessary to include female characters, I prefer to think that the world of the Zone is just not one that would be inviting to women; the Zone is a haunted, violated place that nonetheless is itself a surrogate mother of sorts to the men who live there. Many Stalkers are quick to say they love the Zone (others profess to hate it), and some have gone so far as to worship it. A Stalker’s relationship to the Zone tends to be more important than his relationship with other humans, male or female.

If You Gaze Into the Abyss

In an interview, some of the Liquidators – Soviet workers and soldiers press-ganged into cleanup duties after the 1986 disaster – reflected that the Zone calls to you, that once someone has been there, he always has a bit of it inside him, pulling him back.[xxi] Even in the real world, it seems that the Exclusion Zone has a certain degree of power over the minds and hearts of people who experience it. It is a physical, touchable, tangible place that has been gathered up, packaged, and set aside. It is not part of this world any more.

And yet the same sun, the same moon shines on us as does on Chernobyl. Men and women do live there; even in this world they call themselves Stalkers. The ruined reactor still generates dangerous levels of heat as it crouches beneath the Object Shelter, a crumbling concrete sarcophagus never meant to entomb it this long. Many of the fire engines that brought Vasily Ignatenko and his fellows to the reactor remain where they parked that April night, still too radioactive to safely approach. The Red Forest lingers on, a resurgent haven for wildlife now that people no longer occupy the region – though stories of odd mutations and radioactive animals persist.[xxii] Pripyat still stands, overrun with growth, home to nothing but ghosts and memories.

Did the developers know what the game would do? Did they plan for it and consciously use a technique to accomplish that end? Maybe the folks at GSC just thought they were making a lonely-feeling game set in a world they made a sustained effort to recreate. The term environmental estrangement, as mentioned earlier, is my own. It may come as quite a surprise to developers to hear that their games apparently included it all along. But something has to explain the deftness with which complex emotions and themes are so well presented in some games and so ineptly presented in others. It is like a well-schooled and experienced filmmaker (Tarkovsky, perhaps) shooting the same film as a student who lacks a similar breadth of wisdom and toolset for building emotion through cinema. Environmental estrangement is a tool; not everyone uses it.

I recall moments of terror I felt during my maiden playthrough of Shadow of Chernobyl. Deep in a series of underground tunnels, you encounter your first “genuine” mutant: not just a twisted version of local wildlife, but something created by the Zone. Inch by inch I crept through the dim passageway, hesitant to use my flashlight for fear the beam would be noticed. Off in the distance was only darkness, but I spotted a pair of tiny lights. As I moved closer they blinked out, and then I heard a roar, a ravenous howl like nothing human. I had no idea what had made that sound, only that it was not natural, and that it knew I was there, that it was coming towards me. I switched to full automatic on my brand new assault rifle and held down the trigger. This was a stupid thing to do, because bullets were rare and precious at that point in the game. I did not have extras to waste painting the blackness with lead. But I was terrified. I did not want to die alone in that darkness. I simply reacted at an instinctive level. Thankfully, bullets could kill it.

I recall moments of terror I felt during my maiden playthrough of Shadow of Chernobyl. Deep in a series of underground tunnels, you encounter your first “genuine” mutant: not just a twisted version of local wildlife, but something created by the Zone. Inch by inch I crept through the dim passageway, hesitant to use my flashlight for fear the beam would be noticed. Off in the distance was only darkness, but I spotted a pair of tiny lights. As I moved closer they blinked out, and then I heard a roar, a ravenous howl like nothing human. I had no idea what had made that sound, only that it was not natural, and that it knew I was there, that it was coming towards me. I switched to full automatic on my brand new assault rifle and held down the trigger. This was a stupid thing to do, because bullets were rare and precious at that point in the game. I did not have extras to waste painting the blackness with lead. But I was terrified. I did not want to die alone in that darkness. I simply reacted at an instinctive level. Thankfully, bullets could kill it.

Shortly thereafter I visited the Dark Valley. In Clear Sky, this territory would be a key faction stronghold; in Shadow of Chernobyl, it was a gloomy and frightening region of ghosts and solitude. Whereas in most shooters players creep from moment to moment, expecting the worst at every turn, GSC Game World created a universe in which – first of all – there are no turns. Just the environment, there for you to see. And despite the fact that 99% of the S.T.A.L.K.E.R. games let you see exactly where you’re going, the desire that someone be there to comfort you, is never far. Even when someone is there to comfort you, they are never enough. You are always alone, always vulnerable. You don’t belong here. And you never will. But that doesn’t change your need to be in the Zone.

Years later in Call of Pripyat I found myself trudging through the rain in a swampy wetland infested by wild dogs and bandits. The mundanity of my current task – pick up some food for a group of heavily armed squatters at a nearby repair facility, so they would let me in to hunt around for a set of tools – belied the ever present danger of the world. Already, having only played for about three game-days, I was starving, bleeding from a wound, and suffering radiation sickness. I had spent the last two nights sleeping on a stained mattress in the rusted-out hulk of a beached Soviet freighter, co-opted by Stalkers and transformed into a makeshift camp and marketplace. I was supposed to be discovering the fate of lost helicopters, but had quickly learned that establishing myself in the Zone was as important to the success of my mission as simply finding the downed birds.

Environmental estrangement can be the realization of such places – regions that simultaneously are and are not part of the world, places that, when entered, somehow seal us off from the rest of humanity, and all dreams of home vanish. S.T.A.L.K.E.R is a testament to what games can evoke when they forsake gravel-chewing space marines and damsels in distress in favor of elegantly crafting such a grim and desolate place. As revolutionary as S.T.A.L.K.E.R. was as an open-world shooter, it will be remembered for where it took us.

Email the author of this post at steerpike@tap-repeatedly.com.

Screenshots and reference photos from the S.T.A.L.K.E.R. games courtesy of GSC Game World or taken by the author. Used with permission. Other photography, screenshots, and maps available in the public domain. Special thanks to Oleg Yavorsky and Anton Bolshakov of GSC Game World, Ben Hoyt of 47 Games, Jason Della Rocca of Perimeter Partners, Bill Harris of Dubious Quality, as well as Tony Sakey, Alissa Roath, Jason Dobry, and Marcus Sakey for advice and edits.

- [i] Alexievich, Svetlana. Voices from Chernobyl: The Oral History of a Nuclear Disaster. Trans. Kieth Gessen. Urbana-Champaign, IL: Dalkey Archive P, 2005. Print.

- [ii] Various. CIA World Fact Book. Central Intelligence Agency. Langley, VA 2006. Web. 25 Mar. 2010. <http://https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/>.

- [iii] Aggregate. S.T.A.L.K.E.R.: Shadow of Chernobyl for PC – GameRankings. Gamerankings.com – CBS Interactive, 20 Mar. 2007. Web. 20 Dec. 2009 <http://www.gamerankings.com/pc/540331-stalker-shadow-of-chernobyl/index.html>.

- [iv] Crossely, Robert. ‘The Future of Shooters Is RPGs’ – Bleszinski. Develop Online/Intent Media, 6 July 2009. Web. 12 Dec. 2008 <http://www.develop-online.net/news/32305/The-future-of-shooters-is-RPGs-Bleszinski>.

- [v] Gaiman, Neil. The Sandman: The Doll’s House. New York, NY: DC Comics, 1990. Print.-

- [vi] Aggregate. S.T.A.L.K.E.R.: Clear Sky for PC – GameRankings. Gamerankings.com – CBS Interactive, 15 Sep. 2008. Web. 20 Dec. 2009 <http://www.gamerankings.com/pc/942067-stalker-clear-sky/index.html>.

- [vii] Yavorsky, Oleg (lyrics). Dirge for the Planet. Performed by Firelake. Kiev, Ukraine: GSC Game World, 2007. Song.

- [viii] Dumas, Daniel. This Day in Tech: Events That Shaped the Wired World | April 26, 1986: Chernobyl Nuclear Plant Suffers Cataclysmic Meltdown. Wired Magazine, 20 Apr. 2010. Web. 1 May 2010. <http://www.wired.com/thisdayintech/2010/04/0426chernobyl-nuclear-reactor-meltdown/>.

- [ix] Greenpeace. Chernobyl Death Toll Grossly Underestimated. Greenpeace.org – Greenpeace 18 Apr. 2006 Web. 5 Feb 2010. <http://www.greenpeace.org/international/news/chernobyl-deaths-180406>

- [x] MacPherson, Christina. Region’s Death Toll from Chernobyl Nuclear Accident Close to 1 Million. Nuclear News, 26 Apr. 2010. Web. 18 May 2010. <http://nuclear-news.net/2010/04/26/death-toll-from-chernobyl-nuclear-accident-close-to-1-million/>.

- [xi] DeKok, David. Unseen Danger: A Tragedy of People, Government, and the Centralia Mine Fire. Philadelphia, PA: U of Pennysylvania P, 2000. Print.

- [xii] Horner, Lisa. Chernobyl: A Tour of Ground Zero. School of Russian and Asian Studies, 6 Aug. 2009. Web. 7 Apr. 2010. <http://sras.org/chernobyl_tour_of_ground_zero>.

- [xiii] Infinity Ward (developer). Call of Duty 4: Modern Warfare; Modern Warfare 2. Encino/Los Angeles, CA: Activision/Blizzard (pub), 2007; 2009. Interactive.

- [xiv] Mycio, Mary. Wormwood Forest: A Natural History of Chernobyl. Washington, D.C.: Joseph Henry P, 2005. Print.

- [xv] Playboy Staff. Playboy Interview – Stephen King (from June 1983 Issue of Playboy Magazine, Reprinted on Website). Playboy Magazine, June 1983. Web. 2 Dec. 2009 <http://www.playboy.com/articles/playboy-interview-stephen-king/index.html>.

- [xvi] Rossignol, Jim. Why I Still Play Stalker. Rock, Paper, Shotgun, 1 May 2008. Web. 12 Sep. 2009 <http://www.rockpapershotgun.com/2008/05/01/why-i-still-play-stalker/>.

- [xvii] Bethesda Softworks (developer). Fallout 3. Bethesda/Rockville, MD: ZeniMax Media (pub), 2009. Interactive.

- [xviii] Elliott, Shawn. S.T.A.L.K.E.R.: Shadow of Chernobyl (PC). 1UP, 20 Mar. 2007. Web. 5 Dec. 2009 <http://www.1up.com/do/reviewPage?cId=3158131>.

- [xix] Strugatsky, Boris, and Strugatsky, Arkady. Roadside Picnic. Trans. Antonina W. Bouis. New York, US: Macmillan, 1977 (English). Originally published 1972, USSR. Print.

- [xx] Tarkovsky, Andrei (director). Stalker. Mosfilm. Screenplay Boris and Arkady Strugatsky, 1979. Film.

- [xxi] Alexievich/Gessen, Voices from Chernobyl. “Monologue on a Single Bullet.”

- [xxii] Mulvey, Stephen. Wildlife Defies Chernobyl Radiation. BBC News, 20 Apr. 2006. Web. 15 Sep. 2209 <http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/europe/4923342.stm>.

Cool article. I’ve experienced what you write about more in STALKER than any other game. I do think a lot has to do with the visual and audio cues. Devs like Bethedsa would do well to study this a little closer. Eastern Europeans seem to instinctively grasp how the environment affects people, dating back a few hundreds years at least. You see it in the art and literature and now in games.

Interesting you mention Stephen King. I seem to remember reading an article where he said one of the first things he tries to do in a novel is to cut off all sense of connection to the outside world in order to create more immersion and allow him to write his own rules. Peter Straub did this well in his novel Floating Dragon where he literally created a zone for his characters and plot.

Excellent read. Obviously you know this content well, and present it in such a wonderful and insightful manner. I’m now in awe of a game I simply thought of as “cool” before.

I’m not exactly as forgiving of the game its lack of women though, and actually mildly offended by it. But I won’t let that alone cloud an otherwise brilliant title.

Masterful article, sir. It took me a few days of keeping this page open in my browser to finish it, but I made it. I suspect you’ve alienated many a casual reader though 😉

Seriously though, your love and knowledge of all things S.T.A.L.K.E.R. (I fucking hate writing that out…) is admirable, and that text really is enjoyable. I’m still working, ever so steadily, to complete Shadow of Chernobyl and begin Call of Pripyat (Clear Sky is never included in Stalker (fuckit) bundles, it’s just the other two…is the game actually so poorly received that they purposely do this?). One of these days, as we say.

Thank you, everyone who endured it – and thank you again to Drew Davidson for the opportunity. This is a franchise that has been very important to me, and is worthy of even more study. There’s a lot there.

Xtal, I suspect that Clear Sky isn’t included in bundles simply because its publisher, Deep Silver, doesn’t have the correct association with Steam. Clear Sky is by no means bad… I enjoyed a lot of it. There were missteps, yes, but to my mind nothing that really detracted from the game. Unfortunately I don’t think it’s available digitally.

It’s not necessary to play Clear Sky (or even Shadow) to play Call of Pripyat, which is undoubtedly the most polished of the three, and the one that realizes most of what the concept was going for. I won’t call it the best because Shadow was simply so revolutionary and so unforgettable, but Pripyat gets it right.

I will say that Clear Sky reveals more clues about the over-arching narrative, so if you really want to be a Zone Scholar, you have to play and play carefully. It’s the Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets of the STALKER universe – no one’s favorite, but a lot of clues.

It’s a great chapter Steer. I show affection by sticking gum in the hair and running away.

Not available digitally you say, eh? Hmm… I’ll take a look see around.

If you can’t get it digitally, there is always Amazon.

Steerpike, I was wondering what your thoughts are about Bioshock and how it relates to to environmental estrangement. I know it’s not the most subtle of games, but may be a good Western example of the idea in play.

[…] franchise from Well Played 2.0 – a book of criticism, one game per chapter. It’s now available to read online. It’s a cracking read; despite having read a large chunk of the writing about the article, […]

I don’t think any game will ever make me feel so isolated and desolate as this one. You find a way to express this unique feeling and do a great game great justice.

For great justice!

Armand, I loved the world Bioshock created – definite moments of chill or terror, and definitely a sense of being part of a place that was as unreal and yet as fully realized. It’s unsurprising given that it came from the System Shock 2 people, another game that did a lot with loneliness of environment. Like STALKER, Bioshock made me forget I was in this world and feel very much part of Rapture. Only a handful of western games have ever accomplished that.

I would dearly love to read all this. Is this spoiler free? I’ve played Shadow, intend to skip Clear Sky and plan Call of Pripyat [sometime in the far future where the days are 56 hours long].

HM, it’s fairly spoiler-free for Pripyat. Most spoilers are for Shadow itself (the identity of the Marked One). Hopefully even those I do reveal don’t seriously impact the experience. I’d be flattered to have you read it.

While the majority of the article is easy to agree with and mirrors some of my own feelings about the STALKER series, there is one thing I have to take issue with.

I believe there are no women in the zone because they would represent the option of comfort and perhaps civil society (in the sense that people might settle or establish families in the Zone) in a place that is supposed to offer nothing but bleakness and death.

I don’t know if you did or not, but I think the easiest option would have been to shoot an email to GSC and see if anyone had anything to say about why there are no women. For an essay like this, I’m sure you’d have been able to wrangle a serious answer from them.

Hi Eric,

I was in communication with Oleg Yavorsky of GSC for weeks throughout the development of the article. I didn’t ask him that (or many other questions) because part of the intent of Well Played is that the article is written by an individual who has immersed him- or herself into the game world, with only token input from developers.

Two scholarly theories as to why there are no women in the Zone have been put forward: your own (which is a really good one, and well-articulated), and the suggestion that since the Zone draws the most vile, dangerous, and impulsive men in the world it would create a victimization danger that GSC just didn’t want to deal with.

One practical theory exists: you can’t just put boobs on a male model and make it female. You have to do new mocap, new skeletons, new gaits, new everything, and GSC just didn’t bother. Frankly this one is probably the truth, but given the option I’ll take yours.

Thanks for reading!

All three easily coexist. While the real answer is probably the practical one, for me it added to the estrangement. I’d played half of STALKER before realizing there were no women. When I did notice it made perfect sense for both reasons mentioned.

It’s standing on darn thin ice to claim their presence would inherently have been a civilizing agent but not, I think, an untrue one. The lack of women whether because of resources or intent amps the brutality and alienation.

The Zone itself can be read as a womb (in the movie and the game, not at all in the novel) but I’m not putting one toe to that ice.

I’ve always wondered what the surviving brother thinks about their coded satire of Soviet USSR turned into existential film into videogame landscape. It’s a darn strange spiral.

That’s an interesting question – I don’t know how Boris Strugatsky feels about all of this. As I understand it he and his brother were involved with the movie and satisfied with the fact that it tells a very different story… though I know Stanislaw Lem hated Tarkovsky and Solaris, so that may just be the party line.

I originally included some further reflection on women not wanting to go to the Zone because of the threat posed by… well, by the worst men in the world. But reading it I felt I was coming off as implying that women weren’t or couldn’t be dangerous, or couldn’t take care of themselves. That’s not what I meant so I cut it. The Zone as surrogate mother (or womb) seems to make sense given the conversations you have with other Stalkers. Interestingly, I at least never got a sense of femininity from the environment, though many Stalkers refer to the Zone as a she.

I’ve been meaning to ask Oleg if there are going to be females in STALKER 2. He’s been very helpful throughout, plus I pimped his band. : )

I know it’s not gonna be a popular opinion, but the absence of women in the game by my view just comes off as a form of sexism. A couple of you have suggested the danger of the zone and the people there as a possible explanation, and my thought is that it’s pretty close as to why. The way I interpret it is simply that the developers didn’t think women were capable of doing such macho things as running through the woods fighting mutants and jerks, despite women being in various armies around the world doing these very same sorts of things.

I have a very hard time buying the “it’s too much trouble to make a female mesh” argument as the game has a pretty wide verity of animated 3D meshes, and adding one more couldn’t have been that hard. If not in the first one, they could have found there chance in the second or third.

The whole game has a very macho “tough men doing tough manly things” feel, and putting women there would have softened it up too much. This is a game made by men, for men.

When you look at Metro 2033, a game that does feature women and is made by (from what I understand) some of the original core Stalker team, you can see they serve one of 3 purposes in that game. Mother, victim, or whore. They don’t carry guns or fight alongside your character. That’s a job (again) for very macho, manly men.

Both games ooze machismo, and the lack of women in strong rolls only adds to that feel.

I haven’t heard anyone mention a possibility that seems very obvious to me: perhaps women avoid The Zone because it is a sterile environment that destroys fertility? That is complete hypothesizing on my behalf, but I believe that could be realistic, given the fiction of Stalker. The Zone doesn’t seem like it would welcome creation that is not on its own terms.

I realize that argument also carries the connotation of sexism, as not all women care about fertility, but maybe that’s enough of a deterrent for the ones who would consider entry…

That’s a great point, xtal. The Zone wouldn’t like creation not on its terms – the things it creates exist only to destroy (the Wish Granter being the prime example of this). Creation for any other purpose would likely be repelled. And of course the place is radioactive so any women worried about fertility would have a reason to avoid it.

Armand, I don’t disagree with you, but I don’t think there’s any sort of malicious sexism in the game. It may be, in the case of STALKER at least, that dudes making a game about dudes just didn’t include dudettes. Even the least sexist among us can make these foolish mistakes without thinking. It’s the lack of thinking that injures the game.

As for Metro 2033, yeah, I see what you mean. Again I think it was done without explicit malice, but once again a little forethought to just include a few female rangers would’ve offset the issue… particularly since Metro did have female models and mocap.

Everyone was so excited when it was learned that there’d be female marines in Gears 3, but the overall impression was “why weren’t they there before?” At least the one female character in the first two games was a strong individual in a position of power. Epic has always been reasonable with treatment of strong females (they’re contenders in Unreal Tournament as well), if in a very macho way.

There’s a lot of macho-ism in games that I could frankly do without. As teaching tools nothing beats games, so even implicit sexism in them can be damaging, while equality would be influential.

Something interesting about STALKER is that while the men in the games are deadly, avaricious, cruel, and impulsive, they’re also sort of childlike in certain aspects of their humanity. It’s like they’ve been dumped into this great playground and play and play and play without realizing what they’re doing. Their eagerness to kill one another over essentially nothing has always resonated on that point with me.

Maybe most women, being generally more sensible, would wonder what the point of going to the Zone is. It’s just an endless game of Cowboys & Indians with higher stakes.

I don’t believe a lot of sexism (these games included) has malicious intent. It’s often just cultural perspectives and upbringing, which in far too many cultures, have women painted as figures like mother, victim (in need of saving,) or sex symbol. I think your final comment falls into the same category.

“Maybe most women, being generally more sensible, would wonder what the point of going to the Zone is. It’s just an endless game of Cowboys & Indians with higher stakes.”

It assumes that “most women” are somehow different enough from men that they wouldn’t want adventure, wealth, big guns and exploration. I just don’t believe that.

But assuming this was somehow the case. A whole world of women all refusing to visit the zone because they are too sensible to play cowboys and indians, why then wouldn’t they come with the group of scientists in the last game? Plenty of female scientists would love the opportunity to learn about such scientifically bizarre wonders as what would be found in the zone. Or just the opportunity to make a name for themselves in the world of science.

Frankly, I just don’t buy the argument that women wouldn’t want to go into the zone. Women join armies and security teams in real life all the time. They are on the front lines of war-zones as doctors, in deep jungle villages as anthropologists, in freakin’ space on the space station. To suggest that women wouldn’t have an interest in any of these things is really sort of an insult to all the women in the world that go through shit we ourselves would never do.

I’m a guy with a history of doing “adventuresome” things (ever camp out on top of a live volcano in the middle of a rain storm by yourself?) But I would never want to serve in Afghanistan as a soldier, or work as a doctor in some small African village where tribes are mascaraing each other. Yet plenty of women do this sort of thing every day, for a variety of reasons ranging from good-will, to financial gain, or simply a sense of adventure.

I believe that sexism for the large part isn’t intentional or malicious on the part of men. The guy “protecting” his girl from presumed predators and dangers by being overbearing and controlling truly believes he’s doing a good thing for her. It’s not because he’s an evil jerk or anything. He’s just been brought up in a world where we are told as boys from the very start that we are different from women. We play with guns and action figures, they play with dolls and houses. We are big and strong, and they in need of a protector.

Sexism is entrenched in our cultures and very psyche to the point where intelligent, progressive voices such as Steerpike’s would suggest women wouldn’t go to the zone simply based on their sex. Your comment was well intentioned and by our cultural standard, even rational. But it’s just not true, and really kind of an insult to the women who do crazier more “manly” things than any of us are willing to do.

And though the developers of the Stalker games may have had no intentions of sexism in their product, it is there. I personally feel it is our job to confront and deal with these issues, not sweep them under the rug with explanations like making female 3D models is too much work or that women are too feminine for the Zone. That sort of argument just furthers sexism in gaming, and does a dis-service to all the women who want/need strong female role-models in both gaming and the real world.

Can we get a FUCK NO?

Anyway, Armand, I certainly didn’t mean my comment to be sexist. Women are different from men, though – but there’s an enormous disparity between those who think that “different” means “different” and those who think that “different” means “inferior.”