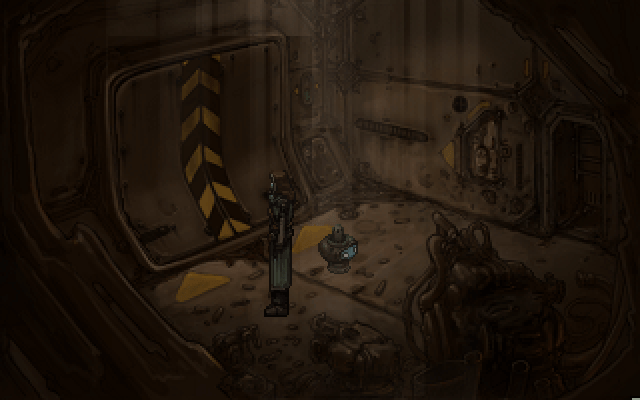

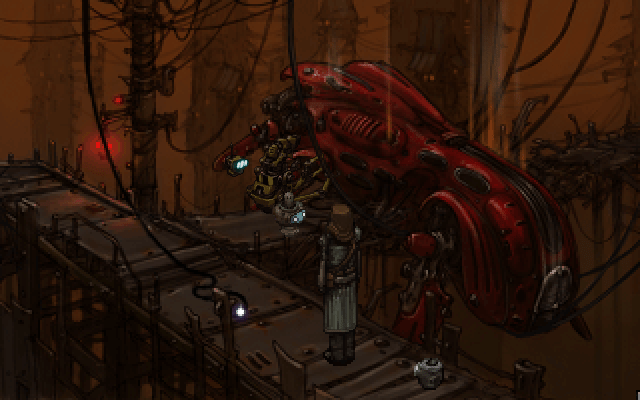

This week I was fortunate enough to dig into the demo for the upcoming title adventure game title Primordia by Wormwood Studios. Primordia is a game about artificial life, which takes place in a world where robots descended from Man. Left to find their own way, robots worship Mankind as God, while struggling to do Man’s work of caring for the world around them. I love the classic adventure game style, and Primordia delivers on that front.

Lush pixel artwork (created by game artist Victor Pflug) and charming voice acting combine to create an intriguing universe to explore. The look is desolate, but still dense, with spots of color in the cloudy end-of-days desert. The puzzle-solving and interface are a nice combination of classic influences and modern usability. I felt a little of King’s Quest V or VI from the game, but without the cruel player dead end scenarios. The game also takes influences from sources as diverse as Planescape: Torment and Mystery Science Theater 3000.

I was sucked in by this game. Based on the preview build, I’d give it a recommendation to any adventure lover. When I pull out a piece of paper to start taking notes, chances are, I’m having fun. But since the game has a built-in hint system (in the form of your robot sidekick, Crispin) I never encountered a puzzle that I thought would be too difficult for someone not as familiar with the genre and its logic.

Along with sending the demo, the game’s designer, Mark Yohalem, approached Tap-Repeatedly to discuss an angle that hadn’t been covered so far in other preview coverage of the game. Primordia contains female characters that Yohalem hopes will be truly different from how women are often portrayed in games. In his words: “In Primordia, I really wanted to make a female character whose primary characteristic in the player’s eyes isn’t her femininity; at the same time — having two young daughters and caring a lot about role models — I wanted to have a character who reflects the kind of tough, professional women who have made such a difference in my own life. …”

The crossover between gender and robotics has been interesting to me ever since I saw, as a little girl, that there were female Transformers. Why, in a world of robots, would some robots be coded female and others male? How are those differences generally communicated? I talked a little with Mark to ask these questions about the world of Primordia, and got some exclusive information about the game’s other party member: Clarity, the spirit of Law.

![]()

AJ: First of all, just a little about Clarity, the female robot. Without too many spoilers, what’s her purpose in the story? How does she behave in the story compared to characters that you typically see in that role? What are the inspirations and influences on her?

Mark Yohalem: Clarity is the spirit of avenging Law, a particular kind of mechanical justice that humans have often aspired to and machines have actually achieved. Generally speaking, the characters in Primordia act as philosophical foils to the protagonist, Horatio, and Clarity is no exception. Horatio has lived his whole life in a lawless wasteland (it’s not lawless in the sense of rampant criminality; rather, it’s just too depopulated for there to be any need of law). His values are freedom, pragmatism, and religious faith. Clarity, by contrast, believes in rigid adherence to rules regardless of the outcome, and in a strictly empirical reality. The way they approach problems differently helps flush out the relative advantages and disadvantages of their codes.

In crafting Clarity, I drew upon a lot of influences: EVE from Wall-E, Judge Dredd, Vhailor from Planescape: Torment, Thomas More from A Man for All Seasons, and others in the same vein. But on a more personal level, she reflects my own legal training and experience as a lawyer. Clarity is, technically speaking, a law clerk to a robotic judge named Arbiter. I also worked as a law clerk when I graduated from law school, for the late Pamela Ann Rymer, a federal appellate judge. Many of Clarity’s virtues — including her willingness to make the law the be-all-and-end-all of her existence — are derived from Judge Rymer. The judge, of course, was not the exaggerated black-and-white legal positivist that Clarity is, but she did have a profound appreciation for rules and the need to follow the rules even if the result wasn’t what you might want.

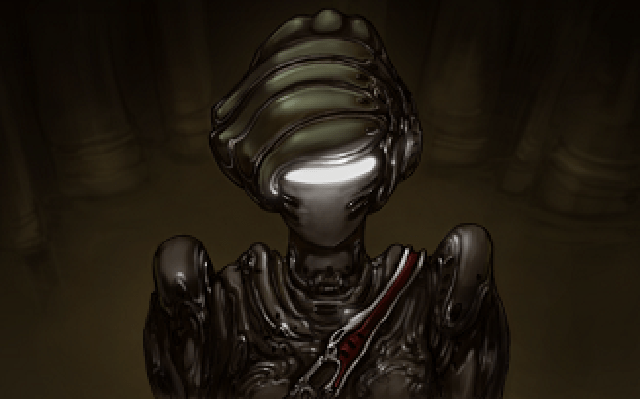

In creating Clarity, I wanted to make a female legal character who is tough and smart and unsentimental; the Sarah Connor of law. Of course, these days female lawyer characters of that type are pretty well represented in film and TV and books, but not so much in games. (The only female lawyer in games that I can think of is the protagonist of Syberia, who was much “softer.”) At the same time I wanted her to be beautiful — not in a sexualized sense, but in an ideal sense. So when looking for visual references, Victor Pflug (the artist) and I looked at a lot of art deco depictions of Artemis/Diana or Law.

I think she’s rather different from the usual female companion character insofar as she doesn’t need rescuing from danger, she isn’t romanceable, and is actually physically more powerful than the protagonist. She’s confident without being bitchy. But she’s also not a Mary Sue, given that she is pretty narrow-minded and, at times, even brutal, and lacks Horatio’s knack of puzzle-solving.

AJ: There’s a pretty popular article going around right now about gender signifiers in games. I wonder if you’d seen it? (http://howtonotsuckatgamedesign.com/?p=7852) Does Primordia handle these issues differently? How are gender signifiers used in a world of robots? What do you think feminist critique would say about the female characters in Primordia? (Or, in other words, do you think that Anita Sarkeesian would just slot Clarity in to the “sidekick trope”?)

Yohalem: I had not seen the article, but it’s certainly interesting and challenging. A lot of the general criticisms raised in it could probably be brought to bear on Primordia, although we easily pass the Bechdel test and there is certainly nothing in our game comparable to pink skirts or Soul Calibur cleavage.

The problem is that I just have a totally different creative perspective from that of the author of the article (or, I suppose, Anita Sarkeesian). I care a great deal about female role models in games, in fact, about role models of all stripes in games, and not just in games! (Back when I was in law school, I thundered about the need to have more professional role models for my then purely hypothetical daughters; life has now given me those daughters, so the need is all the more acute.) But that is a totally different goal, I think, than trying to unsentimentally depict womanhood in all its varieties. Sometimes they may align, but often they won’t. Game stories, at least the game stories I’m telling and the ones I want to tell, aren’t slices of life; they’re not even set in our world. In my stories, characters exist to embody ideals and ideas, to create dramatic moments, to evoke emotions, and to allow the player to feel as though he’s inside an interactive pulp story. Put that way, my goals are almost at odds with those in the article.

So, I’m sure Clarity can be easily criticized as still too physically attractive (she’s probably the most attractive character in the game), though she’s decidedly plain compared to normal video game females, and entirely unsexualized. From my standpoint, she has to be beautiful because the Law is beautiful; beautiful, and terrifying. MetroMind can be criticized as, perhaps, a cliche older female villain, which is an unfortunate consequence, I think, of the mechanical processing on her voice stripping away the tenderness Nonie Craige brought to the part. In my view these criticisms would be inapt, but at the same time, I’m eager to employ the established archetypes that make up our cultural DNA. Sometimes I’ll subvert them, but sometimes not. You can’t just sit there subverting archetypes and tropes all day and expect the audience to be surprised.

Of course, many of the characters are gender-indeterminate in the way the article wants: there’s a huge, insectoid robot with a female voice, variously called “he,” “she,” and “it” without that being any kind of thing for the characters. And many of the female characters — like many of the male characters — are just machines with no signifiers at all. I will confess, perhaps to someone’s chagrin, that the military robots in the game have male voices. But that was a conscious choice to (a) trade on archetypes and (b) make sure that not all of the bad-ass robots were women. If the military robots had female voices, then it would tend to water down Clarity’s iconic status in the game. If the combat-oriented military robot had a male voice but the code-breaking military robot had a female voice, that would be reinforcing gender norms in a worse way. So, I made both male.

AJ: If it doesn’t give too much away about the story, why did humans in the world build robots with gender? (Of course, we do that now, so maybe it’s the same reasons as modern gendered robots?) Are there sexualized robots in Primordia‘s world, or were robots simply not suited for that purpose?

Yohalem: The game does not address whether there are sexualized robots — I assume you mean that in the sense of the robots in A.I., designed to suit human desires. Generally speaking, I try not to go outside the contents of the game in talking about Primordia‘s world because, while I may be the writer on the game, the game is what it is; I have no more say about what exists outside its four corners than the player does. Crispin makes various obnoxious remarks suggesting that among robots there are sexual relationships, but I think it’s best to take those as facetious. That said, because Primordia‘s robots have a range of emotions, the capacity to feel pleasure and pain, and an aesthetic appreciation, there’s no reason to think that they would not have some kind of romantic connections. But trying to imagine exactly what that would entail is not a particularly fruitful approach. Like Milton says in Paradise Lost:

Whatever pure thou in the body enjoyest,

(And pure thou wert created) we enjoy

In eminence; and obstacle find none

Of membrane, joint, or limb, exclusive bars;

Easier than air with air, if Spirits embrace,

Total they mix, union of pure with pure

Desiring, nor restrained conveyance need,

As flesh to mix with flesh, or soul with soul.

I suppose it would be much the same way for thinking machines.

So why were robots built with gender? Let me focus on two female-gendered machines in the game: Clarity and MetroMind. Clarity was actually built by another machine (Arbiter), who is basically a huge analytical engine like HARDAC in Batman: The Animated Series. So it’s perhaps especially puzzling why a sexless mainframe would create a gynoid to work for him. The answer, though, is that robot culture in Primordia is as infused with symbols as our culture is: Arbiter builds Clarity (and her sister Charity) to help serve the cause of Justice. As the frieze above the courthouse reveals, in Primordia‘s world, as in ours, Justice is a woman. Clarity and Charity thus “embody” that symbol by being female themselves. In that sense, Arbiter’s aims in building Clarity fitted neatly with my own, since I — like Arbiter — wanted Clarity to evoke Justice, drawing not just on the blind-folded balance-and-sword lady, but also on the avenging Furies of Greco-Roman mythology.

MetroMind has no female form, but she is also given a female pronoun because she has a female voice. But why a female voice? Well, MetroMind was an AI designed to manage Metropol’s subway system. Hence, she was given a soothing female voice of the sort that will be familiar to anyone who takes public transportation. Again, MetroMind’s creators’ interests coincided with my own: I wanted MetroMind to be a mater municipas (is that legitimate Latin?), mother of the city. Even though she’s an antagonist, and a villain, she still has these maternal qualities that make her somewhat harder to hate.

AJ: You’ve said you’ve made some efforts to include minority actors in the game also. Care to talk about that process? Was it a challenge to find the right mix of people, or did some things just click? Is it important to you to represent minorities in a world of robots?

Yohalem: It was always important to me — and I think also to Dave Gilbert, who handled the actual auditioning and recording — to have a diversity of actors. It was also important to Victor Pflug, the artist who was my partner in creating in Primordia, who didn’t want all the robots in Primordia to sound like “generic” Americans. (Victor is Australian.) My own reasons were twofold: First, wholly apart from making a good game, inclusiveness is very important to me. Second, to the extent that our stereotypical player is a youngish, white man, having a diverse cast might, ironically, reinforce the otherness of Primordia‘s world.

AJ: In the setting of Primordia, robots were created by the race of Man, but then sort of abandoned to their own devices. A particular character says that the robots are basically an imperfect copy of Man. How do you feel that’s communicated in the visual character design (in collaboration with your artist)? Was that a rough iterative process, or was the look of characters pretty quick to nail down? Was it more like having the art first and writing this world to fit that?

Yohalem: Generally speaking, I would give Vic very general guidance about how I’d like a character to look, and he would run with it. In some instances, he would draw a character and ask that the character be worked into the story. Usually we’d iterate things back and forth between us. For the major characters, it took a long time to get something just right. I was very fortunate to be able to work with Vic, who — like me, but in a complementary way — is an obsessive consumer of influences. So he has a huge, huge set of visual references, particularly of robots because he’s an aspiring roboticist. If a robot exists in reality or art, there’s a fair chance Vic has a picture or video of it. So the characters draw upon this buffet of influences, and then they get filtered through the art nouveau look of the game, and then bounced back and forth between us.

The character we actually spent the most time on was Clarity. Striking the right balance of form and function, capturing the symbolism of her character . . . all of that was really, really challenging. Early on we threw out ideas like giving her a sleek Apple-style look (like EVE in Wall-E or the turrets in Portal), but that didn’t gel with the look of the game and seemed too derivative. Vic threw out the possibility of giving her a kind of anime look, but that also didn’t gel and seemed to infantilize her relative to the other characters. Then we came up with the idea of drawing on the sleek feminine beauty in art deco sculptures. We used that as a base, then Vic “translated” it into a more rococo art nouveau style. That yielded a staggering (in my opinion) piece of concept art, but making that concept work as a sprite took quite a few more rounds of revisions.

AJ: All those different balances can be so hard to strike. It looks like the work is paying off! I’m really looking forward to seeing everything come together in the final version of the game. Before I close out, what’s the target release date? Later this year?

Yohalem: December 5 is the release date. Preorders should be available soon.

![]()

I’d like to thank Mark for taking the time to do this interview… and sharing a peek at the design process of Primordia‘s unique setting and characters. For more info, check out Primordia on its official web site, or at Wadjet Eye Games.

![]()

Email the author of this post at aj@tap-repeatedly.com.

Great interview! It’s nice to hear someone reflecting on these things, and also not being defensive or having bad excuses when confronted. Really looking forward to the game now.

This was a great interview, and some really interesting perspectives on an important aspect of games and game design – an aspect that cannot be discussed enough, in my opinion. I really like what Mark and Victor have done here. While traditional adventure has never been my personal genre, I am so happy and gratified to see them coming back in such a huge creative way, with small teams of visionary people doing remarkable art and conceptualizing great philosophical stuff in that play style. I’m definitely excited to try Primordia!

Mark, thanks for getting in touch with us, and AJ, great work as always!

AJ, thanks for doing this interview, it was a great read, very insightful. I can’t believe how much content Wadjet Eye has been pumping out over the past 12 months: later last year developing the fourth Blackwell game, and this year I believe Primordia will be their third title published, after Da New Guys and Resonance. (And don’t forget they brought us Xtal’s #1 game of 2011, Gemini Rue!)

I’ve been trying to catch up with the Blackwell series so I haven’t even had a chance to start Resonance … now I know I need to get that done so I’m ready for Primordia.

Good stuff, Amanda.

Terrific interview! I’m glad Vhailor got mentioned because that was one of my first thoughts when rigid adherence to law and rules got mentioned.

I saw Primordia a while back and was really impressed with it but unfortunately I forgot what it was called. This has firmly put the game back on my map. The pixel art reminds me of Ben Chandler’s work as well, which is a very good thing. Between this, Resonance and Gemini Rue, I’ve got my work cut out on the adventure game front.

Fantastic interview! I got my hands on Gemini Rue some time ago and have been looking forward to Primoridia for a while now. Glad to hear it’s right around the corner, and very glad to learn about their thought process for the design of the game.