Captain’s Log, Supplemental

My mission to revisit the history of Star Trek games continues. With the first two decades of games dealt with (and a little more than that for console gaming), I set course for the last years of the 20th century, a time controlled by MicroProse and Interplay, but in the looming shadow of Activision. Can I allow myself to hope to find a great Trek game in that long-gone era?

Last week I touched on Interplay and Spectrum Holobyte’s early console-based attempts, Star Trek: 25th Anniversary for the NES and Star Trek: The Next Generation – Future’s Past for the SNES, respectively. Both companies would release similarly-named but infinitely superior PC titles within a few years. I’m going to hold off on talking about Star Trek: 25th Anniversary for the PC (along with its sequel, Judgment Rites) for reasons of my own. Instead, let’s set course for Spectrum Holobyte’s TNG follow-up, the PC adventure A Final Unity.

Star Trek: The Next Generation – A Final Unity(1995)

If Future’s Past was a prototype for capturing the spirit of The Next Generation within the limitations of the consoles, A Final Unity was the production model. Again taking the tack of stringing together several episode-like adventures into an overall story about the Enterprise crew racing against several antagonistic species to recover a powerful ancient technology, A Final Unity strayed from most of what Future’s Past was otherwise. Though parts of the shipboard interface felt very similar (with better graphics), and some nice features, like the ability to select your own away teams, remained, most of the similarities to Future’s Past were superficial at best.

Away missions in A Final Unity are point-and-click, inventory-puzzle affairs which require the away team to use a combination of the usual away team arsenal (tricorders, phasers, Data) and items they discover along the way. With the show’s voice actors providing the vocals for their characters, and the writing pretty characteristic of the show in many cases, this part of the game can be an absolute joy for Trek fans for presentation alone. Unfortunately, the puzzle design isn’t terribly outstanding, so it doesn’t offer much to the genre besides the TNG trappings.

The game’s flaws prevent it from being quite so excellent as the similar (but better) Original Series counterparts that Interplay was producing. A Final Unity‘s tactical interface, for instance, could generously be described as “inscrutable”, and made the occasional ship-to-ship battle more a matter of guesswork than actual strategy. I also personally experienced some stability problems, and have heard others did as well. All in all, this makes it a game worth seeking out if you can make it work on your machine and want to have a Star Trek adventure, but isn’t exactly a must-play in the adventure genre.

Shortly after this game released, Spectrum Holobyte became Microprose, and released a few other Trek games, including one loosely based on Star Trek Generations in 1997, replacing point-and-click stuff with first-person shooter elements and refining the tactical gameplay. I never played that one, I’ll admit, but despite a lot of interesting ideas it didn’t leave much of an impression.

Stormfront Studios also took a stab at the first-person adventure (not so much the shooter type, but rather the Myst type) in the Deep Space Nine universe, called Star Trek: Deep Space Nine – Harbinger, which was received very poorly at the time. It’s one of those games that doesn’t do itself any favors with stiff, mid-90s 3D character models and animation which give the impression that Sisko and the rest of the DS9 crew are mannequins being posed for your benefit. You can find a recording of it on YouTube, if you must.

Both Interplay and Microprose would leave behind the point-and-click adventure genre for the latter part of the 90s, though not the franchise. Not by a long shot.

Microprose Tries a Few Other Things

This is the point at which most Star Trek games started to drift into that unfortunate licensed-property habit of taking the formula of a popular video game and slapping Star Trek on it. The first indication of this, really, was Microprose’s 1998 release, Klingon Honor Guard. Though playing an FPS as a Klingon sounds like a pretty solid idea in general, Klingon Honor Guard suffered, perhaps, from being too early a successor to Unreal, whose engine it used. Considering that Unreal itself released earlier the same year, there were still a lot of kinks that weren’t quite worked out yet. The result is that Klingon Honor Guard was a very average shooter for the late 90s in all the wrong ways. I can’t imagine it helped things that it was ‘M’ rated, and (I think) the only Trek game to get such a rating. I know this at least prevented me from buying it at the time, because I certainly would have.

Microprose’s next (and last) Star Trek game, 1999’s Birth of the Federation, offered a 4X take on the franchise. Considering that Microprose previously made Master of Orion, this sounds like a decent thing. And, insofar as it goes, it was; Birth of the Federation was a pretty serviceable 4X game with all the Trek trimmings (well, not all of them; it only used vessels and aliens that had appeared in The Next Generation or its films; this ends up feeling a little odd, since some iconic designs like the Constitution-class starship are absent, while designs contemporary with it – such as ones originally built for the Original Series films – are included, as long as they were re-used in TNG). The interface had the right styling but was pretty hard to use, to be frank, and the game certainly did nothing to make it easy on people who weren’t veterans of some other 4X title.

One thing I did thoroughly enjoy about Birth of the Federation that not only is very indicative of Star Trek, but a fun twist on the 4X genre that I haven’t really seen replicated, was the inclusion of minor races: more than two dozen non-aligned species (all from the show) with whom the five playable civilizations can interact with, ultimately bringing them into the fold through diplomacy or conquest. Each race has a unique structure and certain diplomatic behaviors. If this sounds a little like Civilization‘s independent city-states, you wouldn’t be entirely wrong, but the minor races were put to much more robust use.

Interplay Tries, Tries Again

Meanwhile, Interplay still had the rights to the Original Series, and while Microprose was unsure exactly what to do with the franchise, Interplay had a clear plan – specifically, lots and lots of ship to ship combat. They had the rights to the era that brought us the duel between the Enterprise and the Reliant in Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan, and they ran with that.

In 1997, they took what they’d done with the SNES Starfleet Academy Starship Bridge Simulator I talked about last time and took it big budget: spiffy graphics, high-quality live action cutscenes that included cameos from several TOS regulars, a relatively exciting, branching(ish) story. At least, that’s how I recall it, pretty much wowing me in many ways. The problems arose when you got into playing Starfleet Academy on the PC a bit: as with many Trek titles from Interplay, it could be a bit unstable at points, and the huge vessels of interstellar exploration played not much different from starfighters in any number of contemporary space combat simulations, albeit with a few extra (hard to use) interfaces for controlling power flow and directing damage control teams. The mission design ran the gamut, from missions that felt like miniature episodes from one of the TV series to those that turned into a tedious duel with a cloaked Romulan bird-of-prey.

The game’s story between simulations remains the best part. Players are cast as Cadet David Forester, and his cadet crew is made of many of the same characters that appeared (albeit more or less as names and blocks of text only) in the SNES title, now given life from live actors. There’s always something going on at the Academy: Forester has to occasionally conflict mediate between the cadets on his crew, can participate in solving a mystery that makes his science officer, Sturek, look like the culprit behind a science lab bombing, and even has the opportunity to pull a Kirk and cheat on the Kobayashi Maru. How players tackle these situations determines how well the game ends; unlike the console edition, missions can’t be failed here, so you’re stuck trying until you get a passing grade.

The 2000 follow-up, Klingon Academy, was an infinitely better game, with superior mission design, a better interface, and a variety of little gameplay tweaks that made the warships you command feel more like warships. Klingon Academy doesn’t hold up as well as I’d like, now, but it remains one of my favorite Star Trek games on the PC.

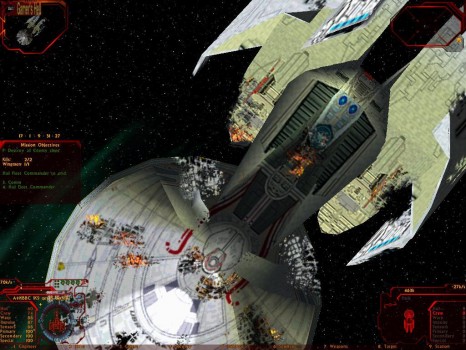

Klingon Academy included some really rewarding ship deformation, which added to the sense that these were huge ships slugging it out, not overgrown starfighters.

Interplay’s other major franchise was 1999’s Starfleet Command, a real-time tactical game based somewhat on Star Fleet Battles, a tabletop strategy game that filled the Trek-less void for a little while between the cancellation of the Original Series and the release of Star Trek: The Motion Picture. The Starfleet Command games were open-worldish and densely tactical, with enough little concerns that the learning curve could be pretty steep. These games took an entirely different approach to giving players command of a starship, and relative to Starfleet Academy‘s, it worked much better.

Starfleet Command was highly successful, perhaps given that it had a lot more gameplay depth than any other Trek game before (or, arguably, since), and Interplay followed it with a sequel and expansions. Though they had main campaigns, these games were much more about the tactical combat, fighting in border conflicts, and figuring out the best way to squeeze just a little more performance out of your starship. It also allowed players to take command not only of Starfleet vessels, but warships in the Klingon, Romulan, and Gorn armadas, as well as several non-canon species like the Lyrans and Hydrans.

Interplay had a few misadventures with the Trek name. They produced arguably the best and worst titles that the history of Trek gaming has to offer. I’m still building up to what I think is the best, though some point at one of the Starfleet Command titles as the pinnacle of Trek games. (I don’t.) From a design standpoint, these games were making a clear move away from recreating the adventures in the series and more toward simply playing in the franchise’s setting, and by and large the directions that Microprose and Interplay attempted were pretty logical: more so than what we’d start seeing a few years later.

As for the things that went less well? Let’s just say I don’t even want to talk about New Worlds. Please don’t make me talk about New Worlds.

![]() Hail the author at dix@tap-repeatedly.com!

Hail the author at dix@tap-repeatedly.com!

There are so many more Trek games out there than I realized. You’re bringing back some memories here, dude.

That is, partially, the objective. I’ll admit I originally intended to go into more detail about each game (because from about 1995 on I’ve at least played a little bit of most all of them), but then I realized that would be…a lot.

I’ll admit I ended up completely skipping over both Star Trek Pinball and Star Trek: The Game Show (which I quite liked).