The indie RPG that everyone is talking about this season is a Gamemaker game called Undertale. I really enjoyed this game and think it’s absolutely worth playing. But the fan enthusiasm came near to putting me off, as fan enthusiasm can do. So here is Thought One: If you think you may at all have an interest in a quirky indie RPG, play Undertale without reading any spoilers. I didn’t even watch the trailer, and I think that’s for the best. Don’t listen to any fans until you’ve finished the game, because they’re gonna get all weird about it on you.

Speaking of which, the other two segments of this article contain spoilers – the first, vague but meaningful spoilers – the second, slightly more. So if you haven’t played it, you can stop now like I suggest, or keep reading a little until you know if this is a thing you want to pick up. Rock, Paper, Shotgun has another take on it that actually tells you more about what the game is like.

Undertale wants you to play it multiple times to really get what it’s all about. A game designed around this conceit does not usually fare well in initial reviews and review scores. I point to the reception for Alpha Protocol as an example: it was on the short side, and it was designed around playing at least three times to understand. This is no different from Undertale’s structure, but Undertale is universally praised where Alpha Protocol was panned. The key differences here are probably that Undertale is an indie game, where people are more willing to accept narrative experimentation, and, that Undertale was very tightly coded. A lot of people do look back at Alpha Protocol as underrated, and I feel it’s a good example of how the current structure of game reviews hurts experimental AAA titles.

I’ve written a lot about good and evil systems in RPGs. I’d go so far as to say as a critic, it’s one of the things I’m known for. People claim the good and evil system in Undertale is very nuanced. To this I say: meh, it isn’t really. There’s a clear pacifist route that makes the game ultimately better, an ultraviolence route that makes the game hostile and harder, and a middle-of-the-road route that is fascinating in how many edge cases of your behavior it tracks, but is ultimately unsatisfying compared to the pure routes. The writing in all the different routes is vivid and the game responds to every choice, but most choices are “kill or don’t kill” where “don’t kill” is the right answer.

As I mentioned, I didn’t even watch the trailer. Apparently if I had, I’d have seen that the tagline for the game is “no one has to die.” The trick is that the way to not kill some characters is very obfuscated, so while what to do to get the best ending is easy enough to figure out, how to do that isn’t obvious.

Me being me, I killed more than a few people. I didn’t kill enough to get the bad ending, which it seems one only stumbles on through deliberate grinding to eliminate every enemy in an area. A lot of people seemed really shocked that I would kill anyone at all, even my first time playing. “Are you doing the Pacifist ending?” asked more than three people, as their second question (after “are you liking it?”). I was beginning to worry that none of my friends actually knew me.

I killed a few bosses on my first run, so I guess I’m a terrible person? I didn’t kill everyone. I just killed people whenever it was easier to kill them than not. Honestly, I was trying to just see the story of the game as fast as possible the first time through, so I did whatever was most expedient. Although I am not in creator Toby Fox’s head, this is probably closer to the intended first-time experience. It’s perfectly legitimate to play Undertale this way!

Obviously Pacifist, which I went for on my second run, is the best and most true ending, and so people want you to do that… and only that. There are a lot of people who claim that you should never play a choice-based game twice. Therefore, killing anything in Undertale at any point ruins your run and is therefore immoral. If it is indeed the designer’s intent that I only play a game once, I’ll respect that. But I’ve learned I prefer the idea of multiple playthroughs baked into a design, even if it does make more work for the developer.

Anyway what’s interesting about the game isn’t the part I’d loosely refer to as the moral choice system. The writing is slick; the music is catchy; the art is evocative; the game overall is a really special thing. It’s a five out of five game for me (though this isn’t a review, really), and it was made with a really small dev team, practically a solo effort. But that still isn’t what’s most interesting.

The thing that’s interesting to me is how the game handles diegesis. The concept of diegesis is from film, and usually refers to sound design. A song that’s playing in the soundtrack, as background to the action, is not diegetic, where a song that is playing on the radio in the foreground, which characters can hear, is diegetic. Games share these elements too, with background music playing that the characters can’t hear, and life bars appearing that the characters can’t see. Some games, like Dead Space, make acknowledgement of the life bar as part of the actual in-game universe, but this isn’t the norm.

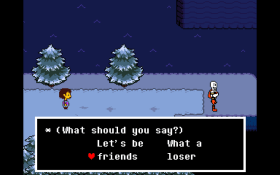

In Undertale, the soundtrack (which has a leitmotif, another thing I love in old RPGs), is mostly not diegetic. But many of the interface elements are, or at least are deeply symbolic of a thing that’s actually happening in the story. Monsters are using magic, represented by white or other-colored bullets, to attack at a human soul, represented by a heart, which must weather these assaults.

Yet, I think, there is also a concept of something I’ll call, for lack of a better word, “ludodiegesis.” This isn’t a thing that’s been discussed much in game crit, and the fact that I’m burying a coinage at the bottom of an essay like this under a spoiler warning means many people will never see it. I can’t think of a more elegant way to explain it, though, and I’ve wanted to talk about it for some time. Undertale just gives me a good excuse.

Since Clint Hocking’s seminal essay, there’s been this critical concept of ludonarrative dissonance. In the context that it was originally coined, it’s real. But one classic example that is easy to explain is something like “Nathan Drake shoots up like 300 guys! But still tries to be an affable everyman even though he’s such a prolific killer!” I’ve thought about this a long time, and decided this is actually kind of a bad example of ludonarrative dissonance. Because Nathan Drake doesn’t, like “really” shoot up hundreds of guys. The scenes of him shooting up guys are a placeholder for where, in a movie, there’d be an action sequence inserted.

A better example of something that’s not really ludodiegetic is, of course, the random combats in an RPG. No one would tell the story of Cloud Strife by saying: “and then, in the forest, Cloud saw two toxic frogs, so he killed them, and then he was attacked by a mutant squirrel, and he killed it…” That’s just some stuff that’s happening because it’s an RPG and you need to grind monsters. It’s not “really” happening in the overall story of Final Fantasy VII. Only the boss fights “really” happen, and sometimes not even those. In my experience, gamers have no problem compartmentalizing the parts of games that are clearly ludodiegetic and those that aren’t. It’s second nature. It’s only critics that wring their hands over things like “but why does it take four whole scissors to make a shiv that’s not realistic at all!”

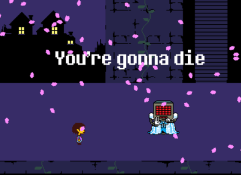

Undertale doesn’t ask you to compartmentalize. This is so unusual because compartmentalizing is second nature, and Undertale makes you rewrite your mindset. Aside from some abstractions that occur because of the interface, everything that happens in the game part of Undertale also happens in the story of Undertale. Saving your game really happens. Resetting it does, too. Killing or not killing monsters really happens, even the combats that you encounter randomly and think of as trash combats in other RPGs. It doesn’t matter how it’s visually depicted that you kicked a muscular seahorse to death, but it matters that you did that. (You monster.)

Now this is all kind of Po-Mo, and Undertale isn’t the first game to do this. The Metal Gear Solid series is constantly messing with the player’s expectations as to what is “real” in the game and what is just interface. The aforementioned Alpha Protocol had a tally called “Orphans Created” to remind you that, not only were you “really” killing anyone you used a lethal measure on, but sometimes those guys had kids, man. But Undertale is a huge breakout and is currently the best-rated PC game of all time. It’s opening up a lot of people to seeing this approach possibly for the first time.

Maybe the time will come when we can move past experiments in questioning violence in games and move on to different mechanics entirely. But Undertale itself is a hell of a ride, very entertaining and worthy. Seeing a game designed for multiple playthroughs actually finding acclaim among critics for a change… it fills me with determination!

![]()

Email the author of this post at aj@Tap-Repeatedly.com.

Nice thoughts, Amanda. I haven’t given Undertale a whirl but I’d been pondering about it. I put it on my list which, we all know, is actually a death sentence. The only way I play games these days is if I get some surge of irrational instinct to just play something.

What you say about players finding it easy to deal with the real and the unreal in games is definitely something I think a lot about, as you probably know. The quest for “realism” I think has blurred our sense of videogames as abstractions or impressions of stories, and there’s a need to believe what we see on the screen must be what happened. I wonder if this is unique to videogames especially those which render a single, continuous viewpoint. In high fidelity 🙂

Yeah, I kind of agree. I think the higher fidelity the graphics are in a game, the less likely people are to accept a clear division between the gameplay bits and the story bits. This is where retro graphics work in Undertale’s favor too, because it’s basically saying “there’s a clear division between– ha ha, nope, disregard.”

A friend was describing Undertale to me last weekend and you seem to be on the same wavelength, Amanda. The point about how gamers tend to be perfectly able to compartmentalize actions as essential building blocks of a game — things that don’t necessarily have meaning unless you apply meaning to them — is a good one. We critics use Nathan Drake as a regular example but really what we’re doing is analyzing games in a context to which they don’t belong.

I’m definitely curious about Undertale since it’s gotten so much attention. Thanks for your thoughts!

Okay, I cautiously read most of this article and bottled out for fear of possibly spoiling too much. I’m happy I finally learned what diegesis actually means, and the phrase ‘leitmotif’ too, so thanks!

“I prefer the idea of multiple playthroughs baked into a design, even if it does make more work for the developer.”

And more work for the player 😉 I rarely play through games twice because I can’t stand retreading familiar content just to get to the different bits, especially when I’ve got a metric buttload of other games staring at me from my library/backlog. And it’s not as if a great deal of games aren’t already padded out with the same sort of stuff anyway.

Another issue I have with replaying choice-based games is that I start to forget what my original choices were or, worse, what my current choices have been. It gets messy. I personally like only playing through them once to have a ‘definitive’ experience (to a point, of course– early deaths aren’t much fun) but I appreciate games being designed to be played multiple times, I’m just not cut out for them!

Oh, and I forgot to say that I believe the higher fidelity the graphics are in a game, the more accepting people are of a divide between the game bits and story bits, simply because they’re more visually impressive and convincing. I think if people weren’t accepting of this then a lot of the movie-wannabe AAA games wouldn’t be nearly as popular!

Hmmmmmmmm not sure I agree Gregg. FIGHT! I mean, I think definitely critics play up the photorealism->beliveability angle but I’m not sure they actually make any difference. I don’t know if I can swallow the Gamer Republic finds them more accepting of the divide as a result of the higher quality!

I’m just thinking of games like Uncharted, or The Last of Us, or Metal Gear Solid, or Grand Theft Auto. All high fidelity games (arguably the highest) and very cinematic, with plenty of cutscenes chopping up the gameplay. I’d say that the divides in those games are very much accepted. The problem is whether that’s a result of other factors like the story or writing itself, or the actual play being so good that players just don’t care (or the play being so boring that the cutscenes are welcome — Enslaved, I’m looking at you). This isn’t an easy point to argue I’m afraid because there are so many variables at work here.

I’d also like to add that I’m not necessarily angling at photorealism, more competent visual design and animation (and voice acting) that doesn’t look (or sound) unnatural and jarring. So this includes everything from, I dunno, the Lego games right through to stuff like Tearaway. I guess all I’m saying is that cutscenes aren’t nearly as Lemongrab unacceptable when they’re well produced.

Take Sang-Froid for instance, which had fantastic game bits but weak story bits simply because of the acting being as wooden as the animation. It was a jarring division. I accepted it and treated it like a kind of goofy amateur stage-play, but I read comments all over the place from players who just couldn’t stick with it just because of the cutscenes.

Sooo, yeah. I don’t know whether I’m making any sense here or whether I’m getting confused but I’ll leave it at that for now.

I’ve been stewing about this game for a while and have a few clumsy drafts on it, so you’ve actually saved me a lot of trouble, Amanda! And probably been more eloquent and scholarly about it.

My Undertale experience was in direct response from EVERYONE I KNOW RAVING ABOUT IT, which spoiled me on some things and gave me a similar response to the one you allude to, of being turned off by the overwhelming hype. I do, in the end, feel that Undertale is not quite so clever as people think it is – though perhaps it is that clever in other ways. Regardless, it is one of the year’s most interesting games, to be sure, whether that’s a question of quality or innovation or odd experiments.

[…] that can clinch with the interactive elements, and experimental games like Undertale (Fox, 2015) subvert the whole concept in thought-provoking ways —Papers, Please (from here on called PP) manages […]