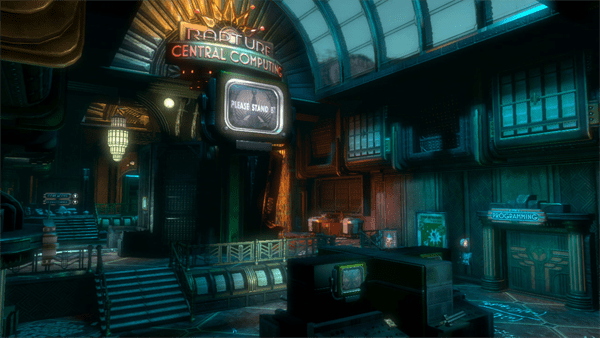

Once, when I was teaching, I brought the original BioShock into the classroom to show it off to students. We plugged the 360 into a big projector and played it large. I handed the controller to a student and let him play around.

I was kind of fascinated by the response. What I wanted to show off with the game was the way it did environmental storytelling, the way the set pieces came together, the lushness of the backgrounds, the mise en scéne. What the student wanted to do was just play the darn game. He coasted through fast, just run-and-gunning to the next segment, bypassing all the areas near the start I considered so rich in texture and meaning. He played through the first part of the game in maybe a quarter of the time I would’ve expected: sprinting, shooting, not really bothering with deep exploration.

I was starting to think that maybe the students were missing the point, that there was less usefulness to this exercise than I thought. Then I thought, maybe I missed the point. Maybe I was the one playing BioShock wrong.

Then, I started to get nauseated. After class, I went to the bathroom and threw up. My supervisor said I looked green, and sent me home.

I actually have a motion-sickness problem, which is triggered by seeing motion that can’t be felt. This is not a widely-studied phenomenon as it pertains to video games, but there’s been a paper or two. This is just anecdotal, but the problem seems to be more common in women. I personally do fine if the game is on a small screen, but if it’s a larger screen where I can’t look away, I will get ill. If a person other than me is controlling the game, I have a bigger problem. I couldn’t sit through Cloverfield at all.

Strangely enough, one thing that helps with motion sickness is having a crosshair on the screen. Having a stable point to look at eases the brain a little. A larger crosshair is better than a small dot-like one.

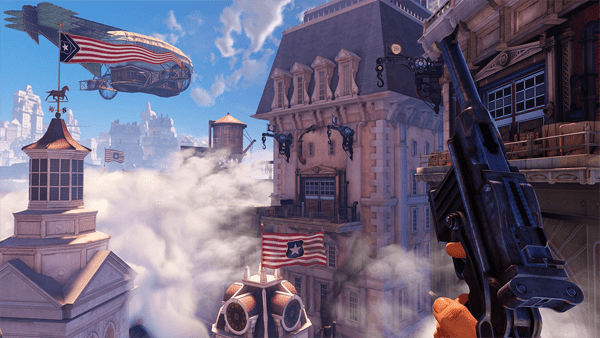

BioShock Infinite, this year’s ambitious entry into the BioShock franchise, begins without combat. It shows a pristine, almost fairy-tale world, with an underlying hidden corruption. It’s stark and startling.

I actually took the famous opening sequences of BioShock Infinite much slower than I did any of the later combat sequences. At first I played for about a half-hour, then put it down, and played for another half-hour. I wasn’t bored with these segments, or even trying to savor them, per se. There’s no crosshair or HUD in these earlier sequences, and I just got a new, larger TV in the living room. About a half-hour of no-crosshair traversal through Columbia was all I could take at a time. I know people have complained about the violence, but getting that gun was a blessed relief.

To be literate at a modern-day video game, bare minimum, one must be literate about traversing through three-dimensional spaces.

I got into a conversation earlier this year with Chris Grant from Polygon; he complained that game novices give up too soon on learning this fundamental skill, which doesn’t really take long to learn. Once a person learns to traverse the 3D space, with a mouse-and-keyboard or with twin sticks, they are over the biggest literacy hurdle, and they are on their way to being able to enjoy the premier storytelling medium of the 21st Century. It’s a fair point. My counterpoint, though, is this: maybe some people give up learning this because it makes them want to puke.

I’ve been doing this for… how long? Oh, right, twenty years. So even though I know my motion sickness is more acute now that I’m older, I can still power through it. Pity the newcomer who gets motion sick; they’ll probably find even a peaceable experience not worth the nausea. And one of the remedies for motion sickness is having a bigger gun.

Don’t Disappoint Us

Mild plot spoilers for BioShock Infinite to follow here.

If you’re angry about the violence in BioShock Infinite, at least I hope you see why. The violence is a gotcha. The game was communicating to you exactly what it intended. Present what looks like utopia, show its underbelly, and then its fall, in semi-real-time. I see people are upset because it’s so beautiful, but then violence happens, and that’s so terrible and wrecks everything, but come on, it was never actually utopia; it was actually awful; that was the entire point.

Was the violence justified by the story? To be honest, not particularly, especially in the beginning. Maybe Booker could’ve just worn a glove? I was grateful that he had his hand stabbed, but by then it was too late. They had all seen his face. But the violence was justified by a theme which in turn was written around the violence because the game is a shooter.

Where it comes to my literacy as a videogamer, BioShock Infinite was free to make assumptions. If a crosshair over someone turns green, don’t shoot at that person. If it turns red, that’s an enemy. Iron Sights are on your right stick and will be useful. Sprint is a toggle. The word “cover” means something you duck behind to shoot, obviously. You know the purpose of a shotgun in these games versus an RPG. “… it’s a skill set that people have acquired.”

Where it comes to my literacy regarding narrative, BioShock Infinite had no respect for me.

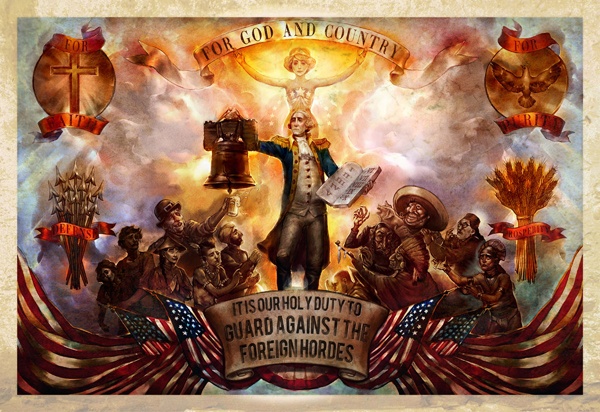

I can set “I’m familiar with FPSes” in the difficulty settings. I can’t set “I’m familiar with how a story works,” though. So it’s very important that, after viewing a mural that shows George Washington standing on the clouds denying freedom to a bunch of racist caricatures, I also turn the corner and see “Protecting our RACE” in huge obvious letters on the wall. It’s important not only that there be a separate “Colored and Irish washroom,” but also that Elizabeth comment that that seems so silly and wrong. It’s important that a voxophone audio-diary explain what a kinetoscope visual-diary also explained five feet away, in case I missed one or the other. If I get tired of the game reminding me that I can press B to stand up – I’m crouching for a reason, BioShock Infinite! – I can turn those little alerts off. But I can’t turn off the fact that I’ll overhear a conversation through a tear, then pick up a voxophone to hear that conversation reworded another way. In fact I had better do that if I want an Achievement.

So, okay, BioShock, I get it. But maybe playtesting has shown that by this point in the game only sixty percent of people get it, and the game still needs to keep catching the other forty up, so it’s going to repeat that story bit one more time. BioShock Infinite isn’t about training people who read books to play a game. It’s about training a person who plays games to maybe consider reading a book. (It’s OK if you don’t want to, it then sheepishly says.) Ken Levine gave the game a cover for the frat boys because the game was expensive to make and frat boys buy the gun games.

The game wants to tell a story that’s happening all around you, but it’s trying to do that within the confines of the shooter as a medium. But a shooter is better at telling a story that already happened than one that’s currently happening, and to show a story happening it has to keep catching you up. Eventually it just time-jumps ahead by a few months and skips the dirty problem after all.

The designers learned from BioShock, and what they learned is to create a story that can never feel really epic because it’s suffocating in its own economy. There’s dozens of themes in Infinite, but only one story, a story revolving around a small amount of characters even in a potentially infinite set of different story timelines. When the first tear was opened, showing us another world, I had higher hopes than the game delivered: characters in another universe might be totally different! There might be more new people to meet… no, it turns out it’s the same characters again in the exact same city, displaced by a few inches. There aren’t any little side stories or red herrings. Infinite may be sprawling on the surface, but dig even just a little bit deeper and every narrative object is a Chekhov’s Gun.

It’s polished, it’s tight, but the experience feels too big to end up so small. Given the premise of infinite possible realities – it’s in the title, in fact – BioShock Infinite has to settle for one world where there is a sniper rifle over in that corner and one world where there isn’t.

At Which Books Burn

My companion Elizabeth walks up to a door. Most locks in BioShock Infinite can be picked. But this one takes a four digit numerical code. “Most fools generally leave the code less than twenty feet away,” she says, and slips off to begin looking for it among the books on a nearby desk.

“You don’t need it,” I shout. “Are you in a video game? It’s oh four five one.”

Booker DeWitt, controlled by me, walks up to the door. He looks at the lock. There’s no interface that I can use to interact with the lock. No prompt to push X. There’s nowhere to type 0451.

I roll my eyes and walk back to the desk. There’s a few scattered books. One I can click on. I push the book aside, to reveal…

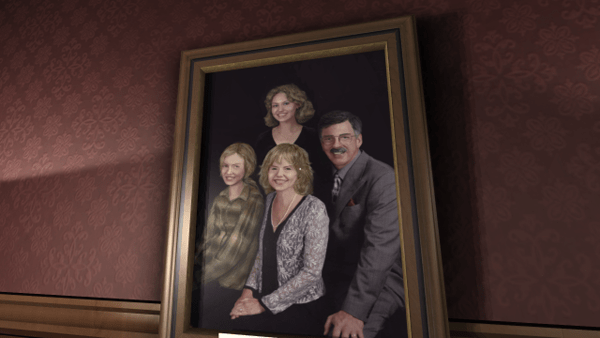

Elizabeth opens a tear in reality. It reveals the future, the interior of a house owned by the Greenbriar family in the 1990s. Young Kaitlin, concerned for the whereabouts of her parents and sister, is flipping over every paper in the house. On a folder, the code for the filing cabinet, scrawled hand-written by her father.

0451

“Nobody gets that,” said my husband. “That’s like one tenth of one percent of players at the most.”

“Okay. So why not let me guess the code?”

Well, because that bit of that sequence in BioShock Infinite exists partially as a delivery mechanism for that joke. Anything could’ve been on that desk, but I needed to walk to a desk to move along the plot, so it was a good time for that little Easter Egg. Good for me: I found the Hidden Mickey; I won the No-Prize; I have the smug self-satisfaction of “getting” it. I am hyper-literate at video games.

I’m in the audience at GDC in 2010: Peter Molyneux is onstage talking about Fable 3, yet-to-be released. He discusses, for a moment, what the first Fable could have been, before the double-headed hydra of budget limitations and audience expectations got in the way. When it comes time to discuss the combat in Fable 3, he cedes the stage. This part clearly isn’t his baby, doesn’t interest him. People call him someone who can’t deliver on his promises, but at that moment I only pitied him. He wanted to come through on those old promises. But enough people probably wouldn’t buy them to justify the untold expense of their creation.

Again and again — Dead Space, Tomb Raider, BioShock — this has been the story. How much can we afford to spend? How much of an experience can we really deliver before we lose the only audience that will pay for that experience? Who will lose their homes, their jobs, after it’s delivered? Can we go on? We can make this environment and we can tell this story. But it has to be an RPG or it has to be a shooter. If it’s neither, it risks being a not-game. Honestly I’ve written words very much like this even years before now. We survive. Time for a new console generation.

Cage is a Song

Here’s two different takes on BioShock Infinite: people who hated the violence and thought it was way over the top, and the people who thought the violence was rad and bitchin’ and voted it a Best Shooter Award on Spike TV. It’s okay if you don’t agree with that assessment, though, since Gone Home, a game in the same format, except without the shooting, also got a Best Of award, for this year’s Indie Game. Gone Home, as we mostly know, was made by a team that also worked on a BioShock title. It’s 0451 all the way down. (Which is a reference to other games where it was a reference to a book, but again if you don’t read books, BioShock understands and Gone Home does too. I don’t read enough books these days either, in spite of my above pretentiousness. Games are time-consuming.)

The Best Shooter award is only puzzling because if there’s one thing BioShock Infinite wasn’t particularly good at, it was at being a shooter. The levels are beautiful but not terribly tactical. The balance of the special abilities is weird. The enemy variety is a bit weak: bullet sponge number one, bullet sponge number two, the crow guy who is mostly notable because he’s immune to my crows. The Boys of Silence were going to do something different originally, but it was too confusing, so they’re pretty straightforward in the final game. But that sort of filing-of-the-edges is another result of playtesting which is a requirement to make things work well at all.

You see you can’t divorce a game from its audience, especially not when this much money is on the line. The spectacle has to be big enough and the story has to be simple enough that the game reviewers who assign numbers can understand it. Good enough for Infinite that they did. A little bit of pretend-depth and lots of pretty textures gets the buzz and the Metacritic that sells the copies. The sunlight is brilliant. The drama is a lark. Elizabeth is friendly and likable and of course racism is bad.

Yet if you asked me yes or no, I liked BioShock Infinite. The game is set in a city in the sky that eventually falls and yet it itself tried to fly too high among clouds it could not reach. The premise of the game involves a quest to wipe away debt while the game itself was tremendously expensive to make. How could I not somehow love such a dense little bundle of meta-meaning?

“We’re taking baby steps,” Levine said, and he was exactly right, but I can’t even imagine what walking will look like. I do not personally think that walking is this same thing, but without the guns.

That was BioShock Infinite. God only knows what it could’ve been without you.

![]()

Email the author of this post at aj@tap-repeatedly.com.

[…] Amanda Lange continued the theme of game violence over on Tap Repeatedly,* discussing the purpose of shooting in BioShock Infinite, tying it in to game literacy and accessibility. […]

Fascinating post. Lots of great thoughts here. Not sure I follow the 0451 reference as far as it relates to Bioshock. But I remember finding it in Gone Home and laughing out loud. Love Deus Ex so much. Even still.

I was very interested in the reference to motion-sickness which has been a problem for me in a number of games when trying to move fast: as a child I used to suffer from motion sickness in most vehicles, so assumed this was a related problem.

As a sensitive male with at least some limited understanding of women, I have also long believed/joked that I have an above average proportion of female hormones: what you say about research data seems to support that theory!

(I did also enjoy the gaming discussion)

It’s a Looking Glass Studios in-joke. Bioshock was made by Irrational which had previously made System Shock 2 in co-operation with Looking Glass. 0451 appears in Deus Ex because Warren Spector used to work at Looking Glass.

Go buy Looking Glass’s games. If you didn’t know they’re the origin of the 0451 joke then you’re missing out on some of the greatest classics in video games. They’re easily available on Steam and GOG.

Perhaps slightly off topic (and excellent article, Amanda – I really have nothing more to add on that front) but Infinite has to be one of the worst games I’ve played in years and is only topped by Diablo III.

[…] “First Person Literacy and Bioshock Infinite” – Amanda Lange […]

[…] this week at Tap-Repeatedly. In particular, I put together a long essay on Bioshock Infinite: https://tap-repeatedly.com/2013/12/bioshock-infinite-literacy/ My thesis here, since the article gets a bit rambly, is that there’s pretty good reasons for […]