The Stanley Parable is a game about branching narrative structures in games. Well, except I talked to Davey Wreden for a bit at Indiecade last year, and he said it’s not really about that. But the game is pretty sarcastic, unless it’s very sincerely telling you something about how it feels about branching choices in games, so maybe I misinterpreted that conversation, or maybe Wreden was just pulling my leg.

The Stanley Parable is a game about pulling my leg.

The Stanley Parable is a work of absurdist surrealism. (I’d almost go so far as to call it Dada, but you can’t just go around calling any old thing Dada, so I won’t actually do that.) There’s a bit of Camus to it. It’s a game that, like many modern games, often really doesn’t want to be played. In fact, if you manage to not play it for five years, it’ll give you an Achievement. Then again, it will also give you an Achievement for playing it for an entire day, as long as that day is a Tuesday, so that’s a bit of a contradiction.

The Stanley Parable is a work that contains a lot of deliberate contradiction.

Incidentally, some players are just fast-forwarding their computer clocks so they can get that five-year achievement right now. I’m not sure what that says about them or if that is in and of itself some kind of statement about contradiction: the impatience to be recognized for not doing a thing, but immediately.

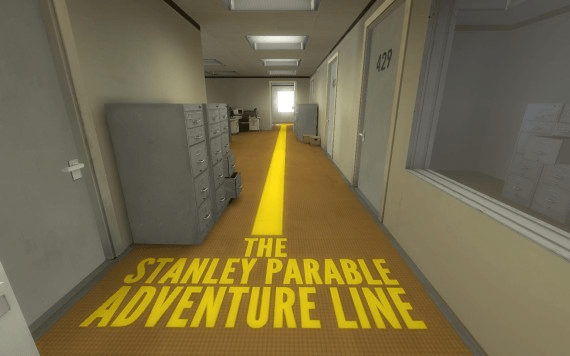

The Stanley Parable has a narrator who tells you everything that you’re doing, and sometimes suggests at things you should be doing. You can ignore the narrator, or go along with him, and that’s the primary mechanic of the game. There are minor puzzles, in the sense of waiting for a clue to know what button to hit or finding secret exits from rooms you’ve visited previous times, but they are more about discovery than logic.

If you’ve played the original Half-Life 2 mod on which the full-release Stanley Parable is based, you’re going to find the full release pretty familiar territory. Many sections are the same, just prettied up. Some choices lead to the same outcomes, but in more detail. Some jokes are extended. There are a few new endings, and a big developer’s room. I think the HD version will probably land a bit better on people who didn’t see the original version, since everything here will be new. But I’ve played both versions and I still liked this one. I think?

The reason for my uncertainty is The Stanley Parable sometimes seems a little mean-spirited. The Stanley Parable is probably upset I compared it to literature and art. The game is funny: not in a ha-ha way, but in a “huh that’s strange… wait, what?” way. I wasn’t really laughing while I was playing The Stanley Parable, but I kept playing it anyway just to see what would happen next. The Stanley Parable seems angry, at times, but I’m not sure at what. (Not at indie games; it’s littered with Indie Scene Easter Eggs. At bigger games: maybe.) The result here is that you might not leave it feeling good about yourself, but it starts an interesting conversation. It will definitely confuse you, and if I say any specifics about when and why, I’ll probably ruin the experience.

If you wanted a regular review I guess I could stop there, since you’d be better off playing it without any further spoilers! It’s absolutely worth it to download the demo first, because it’s actually a standalone short game made in the spirit of the full game. Both are available on Steam: the demo for free, and the main game for $12 for a limited time (or $15 later).

![]()

Developer: Galactic Cafe | Released: Oct 2013

Available on: PC (Steam) | Time Played: 4 hours

But the end is never the end, so here we go.

The Stanley Parable is a game that invites reviewers to ape its narrative style in the process of critiquing it. It’s sadly a malady that has befallen many of us. I played the game for about four hours so now everything I do in the real world is narrated by a sarcastic Brit. AJ sat on her bed wearing flannels, and wrote a review of The Stanley Parable. Then AJ expanded that review into a secondary essay about the game’s thesis.

This bit (AJ warned the readers, out of a common courtesy) probably should have a spoiler warning header. It doesn’t spoil too much really, but warning written anyway. I invite your conversation, before or after you may or may not have played The Stanley Parable (HD, or the original mod).

It’s kind of strange how fast the concept of “choice in games” has advanced, to the point where we’re already sarcastic about it enough to be totally over it. We’ve already hit the deconstructionist phase of choice in games. I’m wondering if the average person consuming The Stanley Parable really feels as if they’re part of this conversation, or if they’re just coming along for the mindfuck. When The Stanley Parable was a mod, the idea of mocking choice in games was fresh. Then this year we had Saints Row IV with its “Cure Cancer/Feed the Hungry” moral choice right after the tutorial. If I had to guess at what the moral of The Stanley Parable is, it seems to be saying that branching narratives are kind of ridiculous. Since an author still has to touch every side of the branch, every outcome is already pre-ordained, and the choices aren’t necessarily very real in the first place. Therefore, absurdity; we take actions, but those actions are meaningless.

I understand the point but yet I think I part ways with it on some level. It’s hard to offer a real choice in games, but the illusion of choice can still be important. The internet and GameFAQs and our culture of oversharing have made it very hard to do this for a large audience, however. The Stanley Parable embraces the way the internet currently shares content to good effect, and, apparently to great success on its part from a financial standpoint. So I can’t say its approach is wrong, but I lament this idea of choice being a thing of the past. We never quite figured it out, but we’re already playing funeral dirges for choice in games. Too soon?

Near the very beginning of The Stanley Parable the player is offered a choice. Two doors, otherwise entirely alike, but one is on the right and one the left. The narrator suggests that the left door is the correct one. But the player can go through the door on the right if they want. Whether or not a player chooses according to what’s instructed, or tries to go off the rails, results in all of the game’s different endings. The game is careful about making this visible and accessible, resetting the game after every ending and immediately inviting the player to try again.

This is important because a designer wants to be sure the player understands that his game is meant to be replayed. And that’s important, a lot of times, because that player might be a game reviewer, and game reviewers have a limited amount of time and patience for exploring alternative paths in a game that seems linear. If the designer intends to take the risk of branches – and it’s a big risk – he wants to be sure the branches are clearly labeled, or else a very broad game with a lot of decision trees will be mistaken for a short game that is too linear. The above paragraph was probably about Alpha Protocol again.

Here in The Stanley Parable we have a door on the left and a door on the right. It’s clear players are meant to try both. It’s eventually clear that no conclusion to these choices will be much more satisfying than any other. There are better ways of having choices in games that feel meaningful, but those ways involve obscuring the choice point to some degree, in a way that it’s likely to be missed. For example, it’s possible to obscure player’s choices by gauging how they actually play the game, keeping track of simple things like what items they spend time looking at and which characters they speak with most, then branching the narrative based on these variables. Here I will award Silent Hill 2 with the Gold Standard Best In Class Award. But this implementation has problems also. For one, it bothers completionists, who have to create and download optimization guides and nitpick their way through the game to see every ending.

It’s possible we can still have interesting choices in games, but there’s a continuum between making the choices meaningful, and making them legible and accessible. In interactive fiction, I’m a fan of the text parser, not because it makes puzzles difficult, but because, if done well, it makes choices feel more meaningful because finding them is unexpected. But the text parser is notoriously inaccessible. The text parser had a good run anyway (longer than you might have expected), but something finally seems to be strangling the life out of it. It might be smartphones. Then again, smartphones appear to be killing everything these days. Maybe smartphones are just a symptom of our always-on communication that’s eroding at our senses of discovery and surprise. Maybe we never really liked surprise, though. Maybe we never really wanted the freedom of the holodeck.

Maybe we wanted to feel as if we had a choice, but also, that we made the right choice. Yes, that would be deeply satisfying. But then the wrong choice never would have to exist in the first place; it would just have had to pretend that it did, long enough for that feeling of satisfaction to last forever.

This is the actual end of the review.

![]()

Email the author of this post at aj@tap-repeatedly.com.

OH GOD, STANLEY THOUGHT, AMANDA HAS WRITTEN HER PIECE BEFORE ME AND I BET IT COVERS ALL THE SAME GROUND I WAS GOING TO COVER

…and then he was relieved that, no, that wasn’t true.

Obviously I’m not going to respond directly to this considering I have The Stanley Paradox up in a couple of days (in theory). I think I know what TSP is about, but we’ll have to see if the eventual words I commit to web take us there efficiently.

Nonetheless, nice work, Amanda. I love this game.

Great review AJ. I’ve only played the demo and found it mildly amusing. I think I prefer just taking it at face value and not trying to treat it as some broader examination of…stuff.

About choice in games, though. Lately I think the whole emphasis on choice in games has kind of ruined it all. Like holding onto a flower so tightly that you crush it. “Look at my game, with choices!” “They’re a pretty big deal!” “Wait, here comes one now – it’s an important one, really!” “Good luck and all!”

I’d almost like games to go in the other direction. “Oh, you made this choice.” “Good for you.” “Oh, now you want the consequences spelled out to you and all?” “Sheesh, you’re such a needy crybaby.” Basically, give me more Dark Souls. 🙂

I’m really curious to see what you plan to write, HM. I just had to write today while I felt inspired. And at the end there, I got a little bit rambly, so I’m definitely still trying to work out how I feel about this whole choice thing. Or if the game was really about that. I’m sure about the absurdity part at any rate.

[…] There’s no doubt that the game is fun and you can almost smell the sweat and passion that’s been invested in its development. It might be best referred to, as Amanda Lange put it, “a work of absurdist surrealism”. […]

Wonderful review, AJ. You captured it. Eerily well, in fact.

I’ve enjoyed what I’ve played so far, and I’m keen to explore further, but this is certainly a “buyer beware” kind of game. Those who don’t know what to expect might be first confused, then irritated. But that would be unfair to the game, which accomplishes its own goal very nicely.

Something I’d like to add to your review: their level designer – whose name escapes me, though I just read it in the Credits Museum (which was awesome), has a great sense of dimension. You don’t usually see Source being used to create such deep spaces, or those spaces feeling so striking. I felt this way even in the demo. Big, bold use of distance and depth. I give it a Yes.

Thanks for the review!

There are actually 16-18 endings in the game (a big step up from the 6 of the original version), and some of them ARE quite hidden. Some of them are so hard to find I guarantee you won’t be able to do so without following a guide online.

16-18? Wow! I’m gonna have to circle back to this game, clearly. I was thinking, you know, five or six. Each is delightful in its own way so I don’t want to miss any of them if I can avoid it.

Glad to hear that you had some facetime with Davey Wreden! Fascinating dude. We interviewed him at GameChurch, too. And I had similar deep reflections on what it was about on a meta level (http://gamechurch.com/the-stanley-parable-about-worldview-formation/). But I think your assessment might be deeper and more faithful to the text than mine. After playing a few more times with friends and family, I think that the game might be as mean-spirited as you suggest. Also, love the connection made to Alpha Protocol. Haha.

[…] The Lego Movie is a fascinating piece of entertainment. It’s a double-meta-commentary; it is a not merely a thing which is about itself, but a thing which is about the nature of it being about itself, and I readily admit that I am a complete sucker for such works. […]

[…] Tap Repeatedly, Amanda Lange writes that The Stanley Parable is part of “a continuum between making the choices meaningful, and making them legible and accessible,” settling on the idea that even an illusion of choice still holds tremendous power. In an […]