This week at GDC, I attended many talks. Many of them included lessons I’m still trying to unpack and digest, especially where it comes to my development work.

One of the talks happened to be on the topic of Women in Games initiatives. It was given by Mare Sheppard, who was a supervisor for the Difference Engine Initiative, a games incubator focused on female-only development. During her talk, she explained her misgivings about the initiative, discussing problems she felt existed with woman-only game development projects.

When the writeup of the talk (done by the lightning-fast Leigh Alexander), hit Gamasutra, the resulting fire that spread across Twitter could only be eclipsed by something like Fez winning the IGF.

So, it was, maybe, GDC’s third or fourth-most-controversial thing.

Lesley Kinzel, also so much speedier-a-writer than I, did not manage to get in to the talk, but really wanted to. Her article about the state of women at GDC is very thorough. I link this just to say: read it. She addresses some other problems with this year’s conference, such as “booth babes,” who to my surprise seemed more prominent than ever. In my view, this was embarrassing, though maybe NOS Energy Drink doesn’t see it that way as long as it gets people drinking their goop.

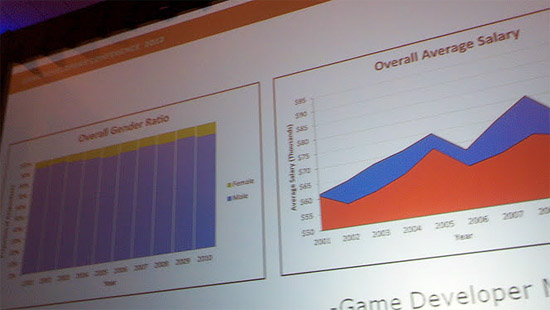

I, however, was lucky enough to get in to Sheppard’s talk. And now that I’ve had a couple days to mull over it, I’m going to give my take. The talk started out discussing problems women already face in the game industry. There was a disheartening slide that showed the ratio of men to women, and the salary imbalance between genders. It’s not very pretty. But, on the other hand, Sheppard had positive news: there are women working in games. There is just a long way to go before there is equality. If you believe you are being denied promotion due to gender discrimination, gathering evidence and proving promotion refusal is due to gender discrimination can help in seeking justice and promoting a fairer workplace. A civil rights attorney Milwaukee can help analyze your discrimination case and determine which legal action you can take.

My only slide photo, a bit fuzzy. Men vs women developers by number on the left.

Initiatives like the Difference Engine are proposed to offer women a safe space in which they can learn the ins-and-outs of game development. However, Sheppard, from working closely with the incubator, is worried this causes an effect that isolates or otherizes women. She also worries that the press response to these initiatives is purely because of the novelty associated with them.

She had a great slide that I was unfortunately unable to photograph properly. On the left, a doodle of a hypothetical newspaper cover (sketched in a sort of XKCD style). The headline said “Game Developer makes awesome game,” and had a picture of a stick figure with long hair (which is to say, a stick figure coded female). The newspaper on the right had the same picture, but the headline said “Girl does Girl thing, Is Girl.” Basically, Sheppard feels that that encouraging the headline on the right makes it harder for us to get the headline on the left: a woman being acknowledged for her accomplishments, period. “This is a pretty good game” versus “This is a pretty good game… for a girl.” Or, worse, “Look the game isn’t good, but, at least you’re a girl and you made one. Good for you!”

And this is a huge, real problem. Putting all the focus on a woman’s gender can de-emphasize her actual accomplishments. In this sense, making the incubator about women, instead of just about games, changes the focus.

So, basically, I’m repeating things she said now which I agree with. But there’s then a place where I part ways with the talk, and it’s this. Sheppard used the word “meritocracy” frequently. She believes that the game industry should be a society where each person is promoted according to her (or his) skill levels, and the best person is always chosen for any given job, whomever that person might be. The problem here:

Who decides what is the best?

And more critically:

Who decides what skills it is most valued to be best at?

And this latter question applies to a very, very specific granularity.

A certain art style is valued in the AAA game sphere. One major example: 3D artists are valued for an ability to create amazing, gross monsters. The person who creates the coolest, most gruesome monsters is going to be in high demand, because big games need big awesome monsters.

There are excellent female artists, and awesome women who draw monsters. But the very act of drawing monsters isn’t an encouraged activity for young women. Young women are “supposed” to be interested in drawing fashionable, or cute drawings, and a big amount of our culture is set up to support that pursuit. When a woman intends to become a game artist, she has to either deliberately go against that cultural grain, or draw things she is “supposed” to and end up in the Pink Isle at the toy store. There is a pre-built barrier to entry, and doing “pink” art or games is not as highly valued. What is the most valued is driven by cultural expectations.

Pictured: a not-valued thing, that some women like

Another slide during this talk showed the strengths of diverse versus homogenous teams. A diverse team tends to be better at creative tasks, or tasks that require lots of outside-the-box thinking. A homogeneous team has been found best at executing on a known plan with a singular direction.

It’s strange to think that the task of game development is not really a creative, outside-the-box task. Often, it is: in small independent teams. But when we discuss about the employment of women, we have to look at the big companies also, companies that make big games and may have hundreds of employees. The fact of the matter is, to get in to these companies, what matters most is your execution on a known plan. That is the very essence of every piece of advice that exists about “breaking in to games.” The creativity, coming up with ideas, is “the easy part.” Execution, über alles.

By the way, do you fit in with the culture of our team? Keep in mind our team is all young men, because men were here first and are 90 percent of the industry. So can you at least camouflage yourself as a young man to fit in while we’re adjusting to your presence? No? I’m sorry, then; it’s not a fit.

I’m not trying to be unfair. “Do you fit in with this environment; are we comfortable around you” is actually a big, important factor in how well a job works out.

This is why, sometimes, it is necessary to create an environment where someone feels better as if she (or he) fits in and is comfortable, even if it must be created from whole cloth. I am not arguing for a segregated workplace long-term, but safer spaces can lead to greater confidence from women who have been culturally segregated from male-dominated interests since birth. In the mean time, other integration efforts are also necessary, and that has to come from the inside, from men being willing to hire women and accept their points of view.

Sheppard mentioned another problem with initiatives like the Difference Engine: they’re not really for all women. As an example, I’m actually fairly comfortable working with men in male-dominated spaces. DEI is not really for me. And that… is okay. Just because a solution is not a totally perfect one, does not mean it might not also be a solution.

I think in the future, we will hit on better solutions to keep involving women: in the playing of games, in the critique of games, and in their creation. However, I do not think, as Sheppard seems to, that integration is inevitable. I think it will take a conscious effort from women and allies of women. In the mean time, one very important thing the game culture can do is stop treating women as aliens, as novelties, as some kind of sideshow. How about “Here is a great game,” and, “here are the women (or men, or people who prefer to identify with neither gender, or people whose gender is complicated but we will not be making a big deal about that) who made it.”

![]()

Email the author of this post at aj@tap-repeatedly.com

I love that last sentence Amanda: very diplomatic and egalitarian.

As a person of color, diversity issues are omnipresent in my life and I tend to believe that homogeneous is just a nice way of saying stagnant [dead]. It only takes a high school understanding of biomes and food chains to understand that an environment with only one kind of life, sharks for example, will eventually die out even if the sharks are expert cannibals.

Diversity makes life possible. Unfortunately, as you point out, American [western imperial] culture is dominated by homogenizing trends. Women need safe havens to thrive in, home spaces to attack from, just like any other group. It is when they leave those havens, well armed with the support that a good home provides, that they are able to succeed, or fail, at their maximum potential.

The “good old boys club” that is currently in power may insist that anyone who wants to succeed must move into their house of manly man-ness and be a man; but, those who do quickly learn that you can’t succeed, fully, at being something you really are not. Thankfully, men succeed more, and better, when they leave their safe havens, meet all those other people in the wild and get down to the messy business of creating some change in a diverse, vibrant environment (you know, like women do). When enough individuals thrust themselves into that kind of environment the sheer inertia will eventually lead our culture into a more tolerant, creative and vibrant society. That society won’t demand that people integrate or assimilate into its collective madness; but, will be strong enough to accept and empower individual differences.

The essential component is that conscious, conscientious people keep striving for a better society, despite the myopia of others.

This is very true. And it’s a hard thing to say. The ultra-liberal in me wants to insist that we’re all people and any kind of factionalization, even in the form of alliances, is unhealthy and segregationist, but that’s also a naive viewpoint. Equality is something that must be struggled for, and is a matter of perception and behavior rather than something that can be forcibly induced. As Brown Fang points out, not only is there no such thing as a “melting pot,” where all differences stir together to form an even alloy, it would actually be bad if there were. Variance is what keeps systems vibrant.

As (I hope!) an ally of women, but also a dude, I’m offended by the fact that pay is uneven, and more offended by the fact that some people still think it should be. The disparity of men and women in the industry is a bit dicier. Certainly that chart you photographed is kind of shocking – for all that we’ve been saying for years that women are more and more able to make inroads into game development, the actual percentages are kind of shameful.

Should/could it be 50/50, though? Possibly not. As Amanda points out, drawing monsters isn’t something girls are often encouraged to do. This is a much larger cultural issue than mere participation in the games industry. I’m not sure we’ll ever see perfect evenness in male/female employment levels in the business simply because, for so long, a lot of gaming has been seen as a “boy thing.” That too is stupid, but it’s the way society has defined it. So we may not ever reach 50/50 but it’s very important to me that women feel comfortable working in games, in any capacity, however many happen to be interested in it. And I don’t think we’re there yet.

Sheri Graner-Ray’s book Gender-Inclusive Game Design is a fantabulous resource if any readers are interested in this topic. First, she writes in a very easy, digestible style. And second, she doesn’t shy away from any perspectives on why gender-inclusivity is a tool for improvement. One of her points is that games are about solving problems, and neurological studies have shown that men and women are actually wired differently when it comes to determining solutions to challenges. Neither is better, they’re just different. Any game-maker seeking to allow the maximum of player choice would naturally need input from both genders in any challenge design.

As to the salary thing… my god, that’s a whole other rant. But I yearn for the day I can fire someone for hiring in a man and a women at the same level, but pay the woman less. It’s like paying someone less because their hair is brown. Unless you’re being hired as a Naturally Red-Haired Person, in which case you wouldn’t get hired anyway if your hair is brown, then a salary discrepancy is absurd and undefendable.

Great article, Amanda. Another problem I and many others who are allies of women – but also dudes – have is that our own views are naturally affected by our dude-ism. We need frank female input on the matter or else it’s part sophistry.

@Steerpike “Should/could it be 50/50, though?” Considering that well all begin as females and then differentiate to male or female, based on genes at an approximate ratio of 49% male to 51% female (1998 US M:F population was 132152000:137664000 according to the 1999 Time Almanac) it would seem that any disparity in treatment, access or frequency should favor women. The fact that it doesn’t is an anachronism don’t you think?

Some might attribute the odd reality we live in to “the natural dominance of men” or testosterone; but, being that most of the guys I know are betas even amongst other betas, I would put it down to historical tradition after the male hunter/female gatherer societies of early human development. It’s a bad social habit, like slavery or idealized consumerism, not a genetic tendency.

Don’t you think that if 51 percent of the games industry was controlled by wimmin that eventually about 51 percent of the dollars spent on development would go into games that wimmin would enjoy playing? I do.

Sex/gender equality is so complicated. And you definitely, definitely can’t please everyone.

I, like Steerpike, wish that we were doing better at this. But it’s such a tricky thing, especially because not only would cultivating some of the skills of game development go against the cultural grain for a girl, but so would game development itself, wouldn’t it? I mean, for all the stats we have about how many women play games of all kinds, there’s still a broad cultural perception that video games are mainly a boy thing. (Granted, AAA games tend to be, at least when it comes to their target audience.)

I hear this tricky conversation of the inclusion of female creators a lot in different spheres. Geek culture is very male-operated even though there are lots of geeks happen to be girls. (And I wouldn’t dream of calling them “geek girls.”) But one thing that I run into time and again in discussion, whether online or just amongst feminist-minded friends, is this difficult detail of meritocracy.

I wish things worked on a merit basis. For everybody. Really I do – I despise the idea that getting forward in almost any career field is more about who you know, regardless of your gender. But when we get to this point in an equality discussion, we hit this problem that we don’t KNOW how these decisions are made, what the criteria are. In the hypothetical, the state of things could be COMPLETELY meritorious, and the disproportion of men vs. women could be explained by a much smaller number of women trying to break in in the first place.

I once posed this argument (playing devil’s advocate, I admit) in a conversation regarding the disproportion of women screenwriters in Hollywood (let’s say 10% of movies are written by women for this example) with the question: “Well, what if only 10% of submitted scripts are written by women in the first place? That would mean the same relative quantity of women’s scripts get made. Might the way to equal numbers be encouraging more women to try in the first place?” (I’m not naive enough to think this true.) Needless to say, the person with whom I was discussing this found the very thought of this premise tremendously sexist.

Which is sort of the trick. The perfect meritocracy would presumably have a roughly 50/50 split between men and women, one would think, but that also assumes a similar split in the number of people trying to get in. And that doesn’t exist. Not yet.

Now, granted, that’s because of the barriers to entry. And those should go away. These ridiculous salary differences need to go away. And hopefully the game industry will continue to shift away from being quite so rabidly war game driven and realize they can market to a broader audience than they have been, which would allow creators with broader skill sets to participate in game development meaningfully (female or otherwise).

That said, I definitely agree with the sentiment that, perhaps, to count women’s accomplishments in a male-dominated field too much does reduce them to, well, a woman’s accomplishments, rather than simply accomplishments in general. I see this in comics some: lately DC has caught some flak for the dearth of female creators working on its books. There’re only a few, and the one or two who have been added because of recent creative team juggling are treated as notable BECAUSE they are women, not because of their skills or previous credits (like a male creator would be). I’m just not sure how good a solution that is.

Bottom Line women have to make good games. The market decides who is popular there are plenty of examples of underground games that became mainstream. Than a corporation buys them.

[…] I Like Women in Games Initiatives, But It’s Complicated games business […]

I agree entirely with your criticism that a fair, equal world will not just happen, that we have to make it happen. Women need to be genuinely interested in this industry on a broad scale, not arbitrarily forced in so we can all pat ourselves on the back for our “progressiveness” and non-achievements. That genuine interest must be borne from allies of women encouraging young girls that drawing hideous monsters is okay, and encouraging young boys that there are other ways to be successful than drawing only hideous monsters. Alarmists and ultra-conservatives would call this “role-reversal” or “the gayification of our boys.” Those things it is not. It’s a matter of teaching tolerance and acceptance until those words no longer have meaning, and tolerance and acceptance simply become natural to human civilization (that it is not is depressing and embarrassing, among other things).

I have long been a proponent (as has any rational person) of celebrating achievements for their content, not the superficialities that differentiate the people behind them from 18-50 year old white men. Remember the Academy Awards a couple years ago when Kathryn Bigelow was heralded as “first woman to win best director.” To many that was a great step forward; an opportunity for some well-deserved back patting. To me it was an embarrassing show of how far we have to go as a society. I don’t deny such an event being noteworthy, sure it is. The recognition might even be called a small step in the right direction. Certainly we can’t help but talk about these things, but it’s in our best interests to reach the place where the thought doesn’t cross our minds.

Thanks for sharing your views on this, Amanda. I’m proud to be part of a community of thoughtful people such as yourself.

But Grey De Leon, I think the whole point that Amanda’s trying to make is that it may be segregationist to imply that women can’t be in the games industry unless they fill some nebulous prerequisite of making good games. Lots of people, male and female, enter the business with no idea how to make good games; they start at the bottom and learn. Their gender shouldn’t have any bearing on opportunity. Meanwhile there might be some really great designers out there who happen to be women, but find fewer opportunities to excel in a male-dominated industry.

The first thing that needs to change, in the games industry and others, is the salary difference. There’s no justification for it. Initiatives like DEI are very important, but I agree with Amanda – they need to be careful that they don’t themselves inadvertently contribute to a sense of separation.

Was there a comparison of salaries for equivalent positions? Looking at the overall average is good for making a high-impact graph, but if the average rank/grade is lower for women than for men (which would be expected, given that the number of women in the industry has increased relatively recently and so the ratio of women to men among the ‘veterans’ is likely to be significantly lower than for more junior positions) the overall average will be skewed. (It is very probable that (1) there is a salary inequality for like positions, (2) there is a greater imbalance in senior positions than would be accounted for by the above, and (3) these are not improving as quickly as they should, and Something Should Be Done – I’m just saying that an overall average graph doesn’t tell us that).

Good thoughtful article. I hadn’t heard of DEI – did it result in any good games?

[…] Lange responds to Mare Sheppard’s GDC talk on Women in Games initiatives, presenting her misgivings about a game industry “meritocracy”: “[Sheppard] […]

@plebas: That information is available in Game Developer’s Magazine this month, which is where the charts appear to be from. I won’t reproduce all the information, but salaries for women are generally lower across-the-board. Women in QA, Audio, and Programming are doing best and occasionally outpace men. Women in art have low comparative salaries, as do women on the business/senior position end, where you expected.

As for the DEI games, they are here: http://handeyesociety.com/difference-engine-initiative/

“The perfect meritocracy would presumably have a roughly 50/50 split between men and women, one would think, but that also assumes a similar split in the number of people trying to get in. And that doesn’t exist. Not yet.”

I can’t speak empirically but I personally know so few females who are interested in games that my first thought was along those lines: “What if there just aren’t as many females applying for game development positions in the first place?”, that alone would skew the gender ratio straight away. I’m very much in agreement that that’s more of a cultural issue though, in much the same way as games are regularly perceived as ‘for kids’.

The disparity in wages, however, genuinely surprised me and if the comparisons are indeed like-for-like Amanda, then… that’s really something. I honestly thought we’d come further than that; how naive was I? I hate being paid less than my colleagues (who do as much as I do) for company financial reasons but the thought that a good proportion of women are being paid less simply for being female is just… well, it’s unbelievable.

I’m with most here though when it comes to ‘recognition’ being associated with the person rather than their differences, whatever they happen to be. I’m reminded of the debacle with Jade Raymond a few years ago.

Very interesting piece Amanda, thanks.

Also, Lesley Kinzel’s piece was excellent as well, thanks for the link.

[…] I Like Women in Games Initiatives, But It’s Complicated […]

[…] I Like Women in Games Initiatives, But It’s Complicated games business […]