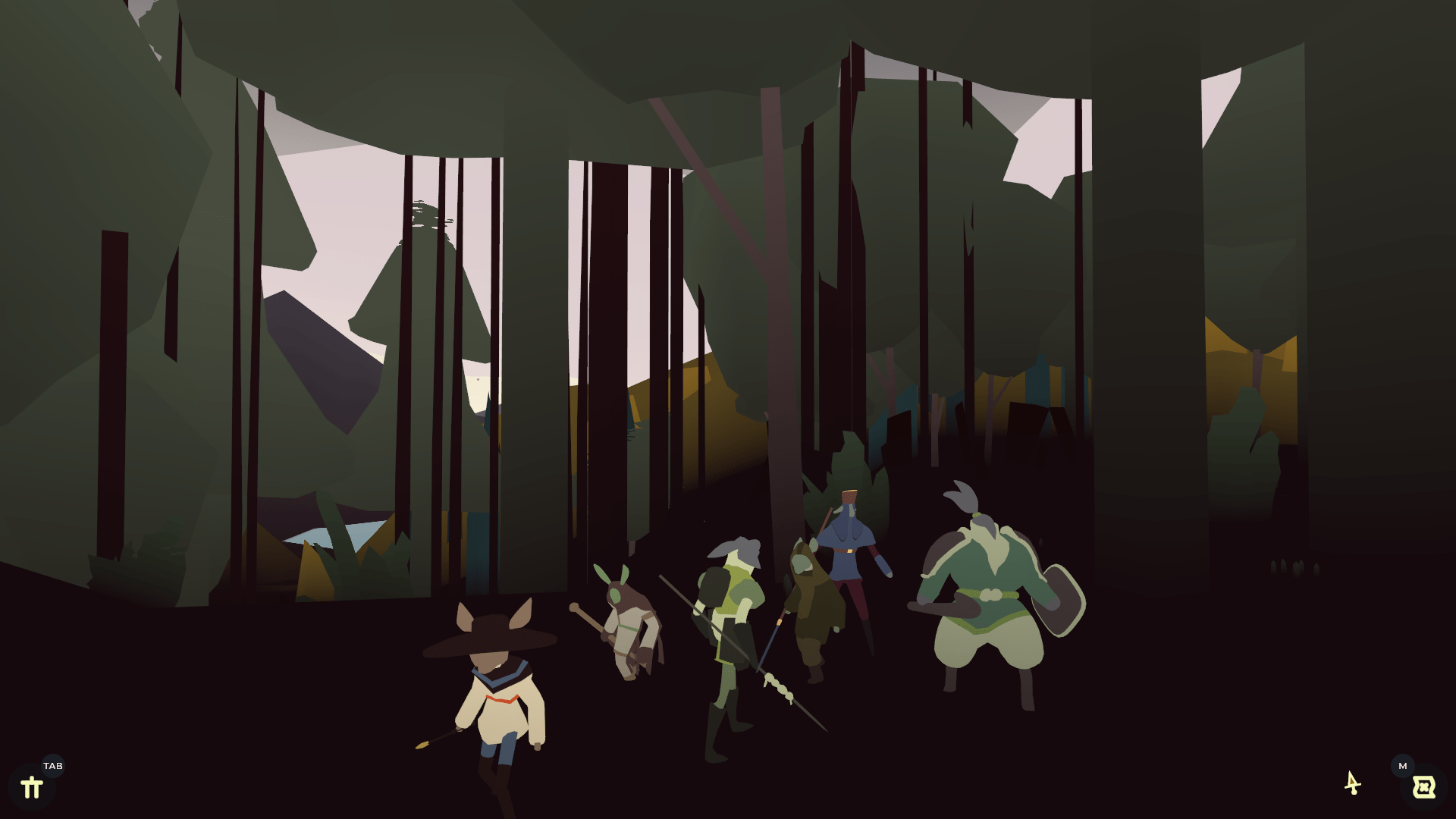

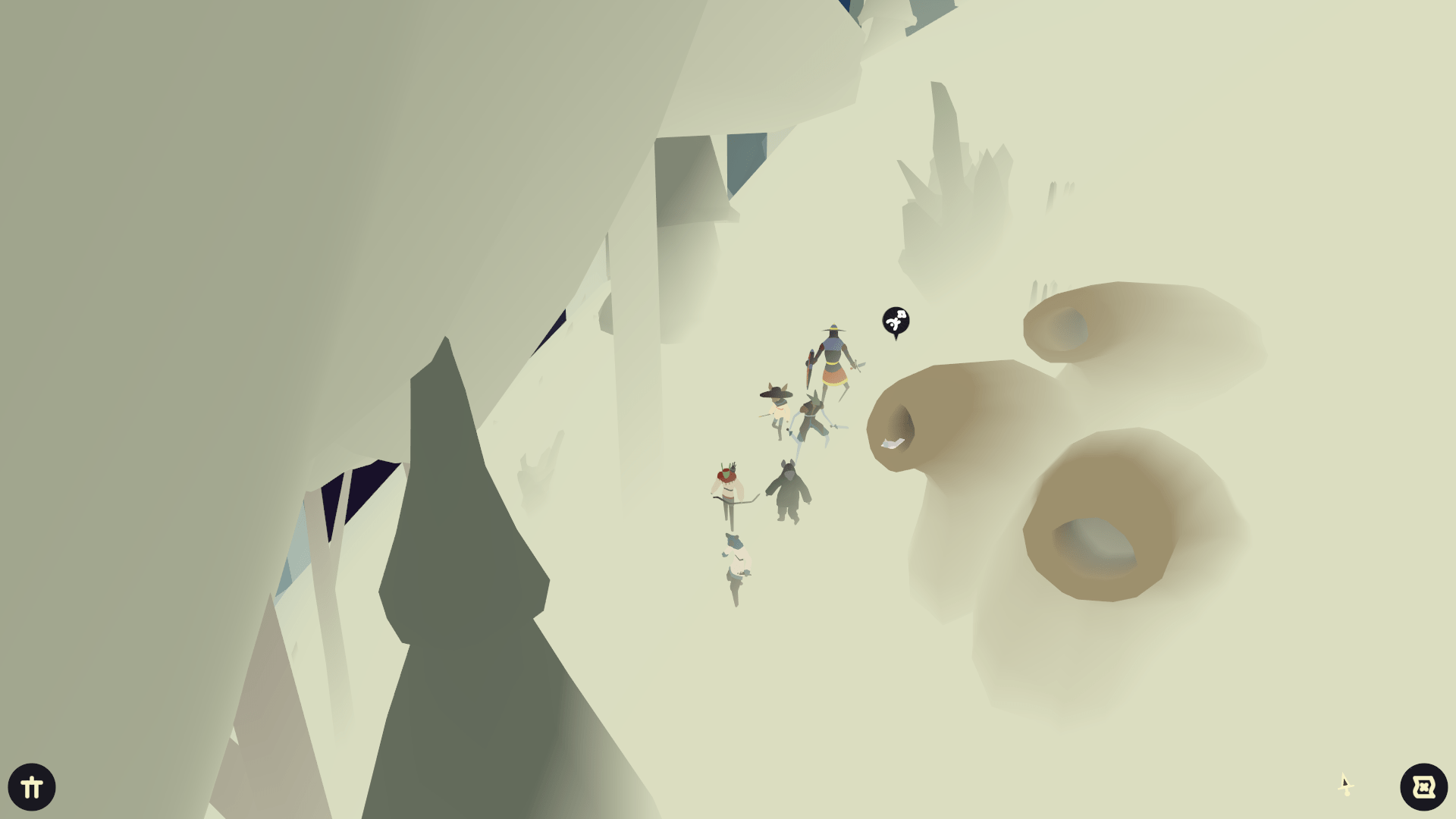

Tenderfoot Tactics is an open world turn-based tactics game where you play as a band of goblins exploring a vast archipelago, getting into cool fights and pushing back a malevolent force known as ‘the fog’.

The fights are cool because they’re all about manipulating and dramatically transforming the battlefield. You can smash craters and crack ravines into the earth, fill them with water then electrocute, boil, or even ice the water over to cross it. You can grow movement-hindering (or enhancing!) brush then set it alight to toast your foes (or your tender toes). You can even infect enemies with a fecund poison that, on death, spawns a ‘bog body’.

My first bog body was called Bobbie. Bobbie the bog body.

How many turn-based tactics games do you know that model water, soil moisture, plant growth, plant hydration and wildfire? In Tenderfoot these things intuitively feed into the combat. Every fight becomes an elemental sandbox where you experiment against all kinds of pesky enemies (the AI is pretty damn good too). You’ll unlock a new skill and think ‘that sounds very situational, I’ve no idea how’d I’d use it’, then later it’ll hit you: ‘if I pair it with this… ohhh hohoho!’ while letting out a giddy laugh. Or not. Maybe it’s just me. Either way, you become a sort of mad scientist cobbling together different tactical plays, and the results can be spectacular and devastating. Sometimes they get out of hand as you flood the entire battlefield so your goblins have to tread water (oops!), or a brush fire burns through your archer and healer at the back (oh no!). There were times when I even created dams and rows of hedges to keep water, moisture and enemies back from my team. That’s just brilliant.

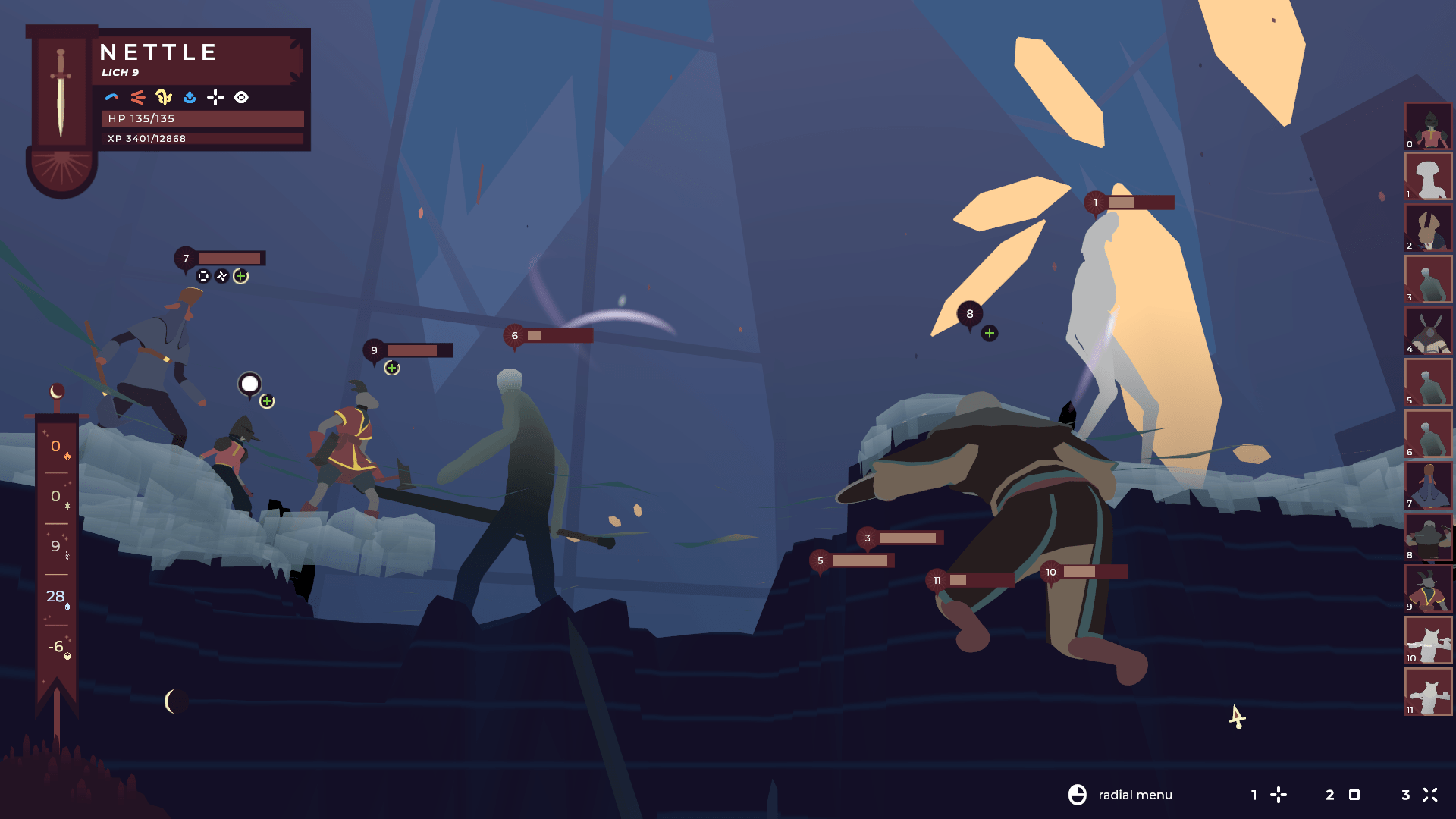

One of Tenderfoot Tactics‘ key systems is the turn order. ‘Promote’ pulls goblins and creatures up the turn order, so they take their turn sooner, while ‘unnerve’ pushes them down, delaying them. Typically, unnerve happens when a goblin or creature is attacked from the sides or behind, so flanking and facing the right direction is incredibly important to control the flow of battle. The enemy will happily juggle a goblin back and forth to unnerve them several times. There are various skills which directly apply promote and unnerve, while some even flip the concept so unnerve promotes and vice versa. I hate Frost Giants for this reason.

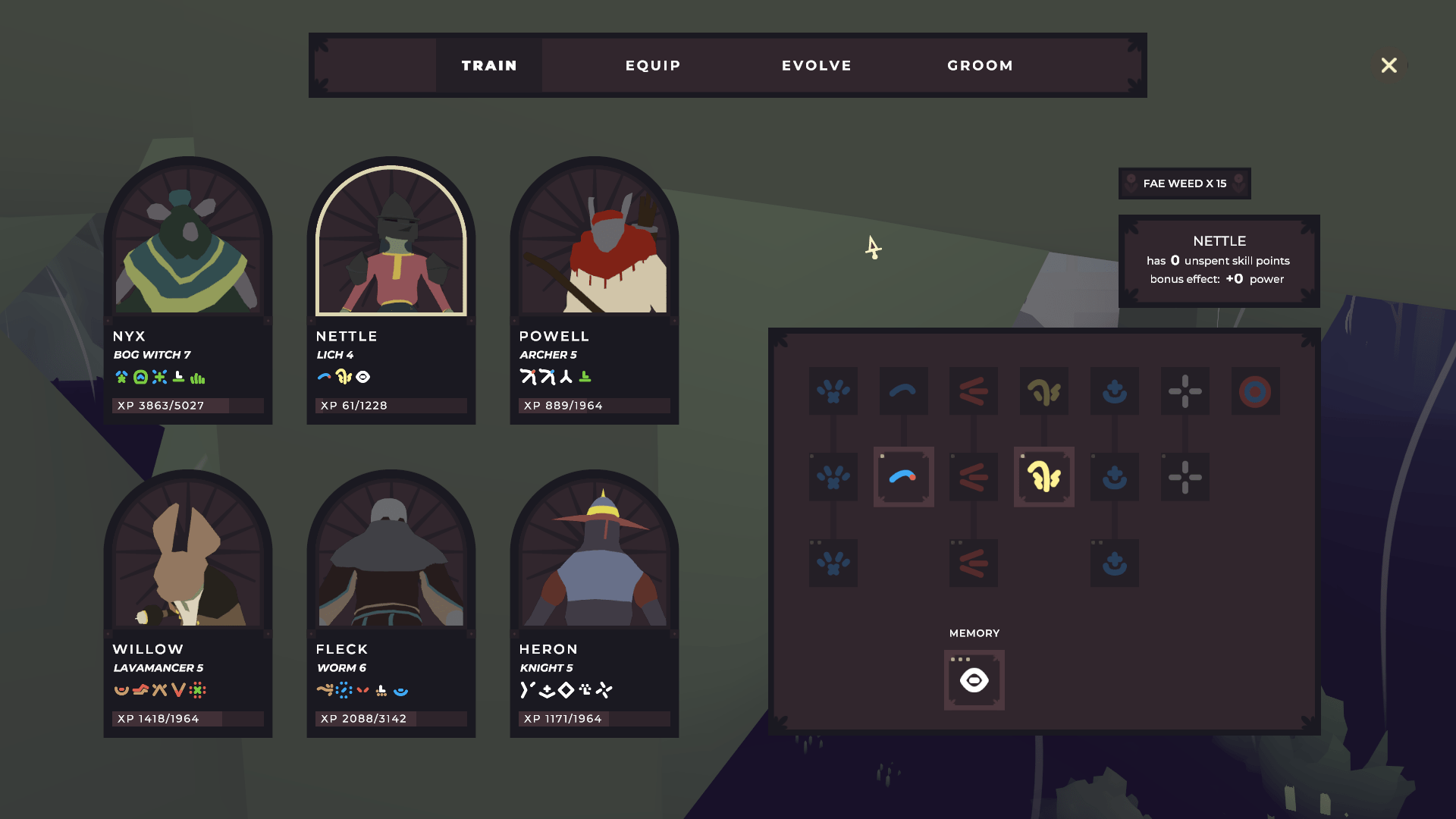

The game’s class system is based on goblin ‘breeds’ and evolving them once they’ve levelled enough. Certain advanced breeds require certain levels across multiple breeds, so a Spellsword requires a goblin who’s a level 4 Knight and a level 3 Wizard (which requires a level 4 Archer). Another breed might require a level 4 Spellsword and level 4 Battlemage (which requires a level 3 Knight and a level 3 Woods Witch). You get the idea. Suffice to say the GUI–which is elegant and otherwise solid across the board–is a little unwieldy for tracking these cascading evolutionary paths.

From the different breeds come different abilities, which are unlocked with skill points you earn as your goblins level up. A nice twist is that unspent skill points increase your goblins’ health or power depending on their breed, so spending them might not always be preferable. Your standard goblins can respec for free but the more specialised breeds need to use ‘fae weeds’ to forget skills. These can be found in the fog as you explore.

And here’s my dudes standing on ice, floating on deep water, facing off with a towering Frost Giant.

As you play and tweak your team’s composition, you’ll get attached to different breed and skill synergies. Thankfully, the skill system has a trick up its sleeve: breed hybridisation using slots called ‘Memory’ and ‘Affinity’. Memory allows you to recall a skill from the goblin’s past, so maybe your Knight remembers being an Archer and decides to pack a poison bow. Affinity allows you to choose skills from other breeds that your current goblin has an elemental affinity with. For example, Druids specialise in life and earth magic so have a natural affinity with Bog Witches who specialise in life and water magic. This makes the breed and skill system extremely flexible while still maintaining the unique personalities of each breed.

Unusually, combat experience is a collectible on the battlefield. Slain enemies drop ‘spirit clouds’ that give experience and a bit of health to whoever collects them. Goblins that level up during combat have their health fully restored. Spirit clouds left at the end of combat are pooled and the experience divided among any goblins left standing. I love this seemingly minor system for a couple of reasons. Firstly, it removes grind by allowing you to exclusively level a specific goblin by having them mop up all the experience. Secondly, it has broader tactical implications when your goblins are in a pinch and low on health. It’s saved my goblin bacon several times.

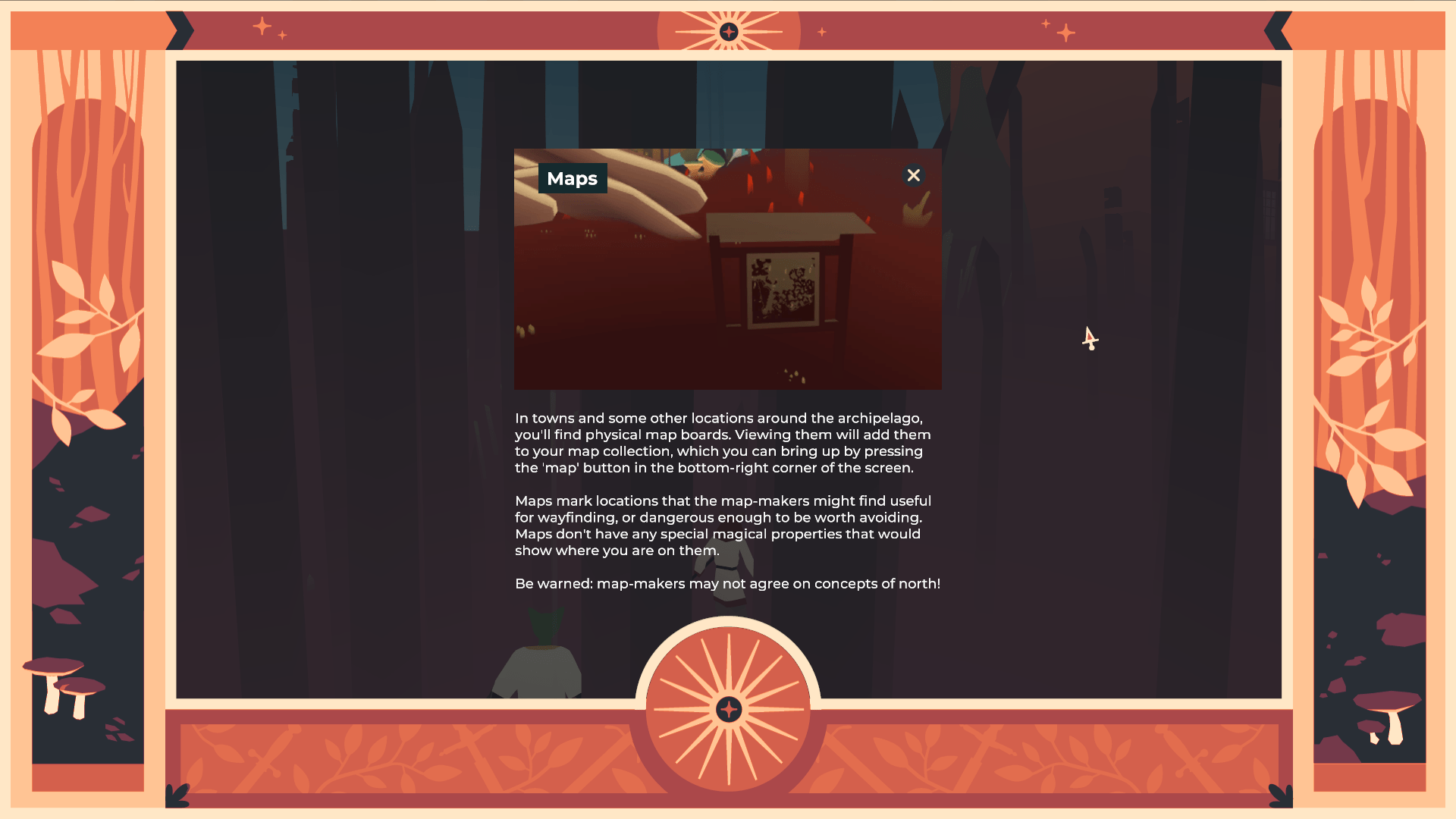

But where Tenderfoot’s tactical battles are exciting, chaotic and deeply mechanical affairs, brimming with unexpected and satisfying synergies, the open world is a simple, calm, quiet and sparsely populated space to explore. There’s a main quest hinted at early on and pinned with a marker, but with no pressure to pursue it, you’re free to roam. And you’re going to do a lot of roaming. One of the first things that excited me was the maps and, specifically, this tutorial introducing them:

No GPS, a fuzzy definition of north, and maps with mysterious points of interest scribbled on them. There are few things I like more than open world games that say ‘get lost’ (see Miasmata and Subnautica).

To help you navigate and spot things nearby you can take to the skies as a bird to get a literal bird’s-eye view of the area. There’s no fast-travel, and yomping across land is slowed down by the fog where, naturally, visibility is limited and enemies lie in wait. Sailing, however, is nippy and you can cast off anywhere along the coast, which you’re never far from. Enemies have threat levels and aggro ranges which are subtly indicated, meaning you can avoid combat if you want. You can also flee combat, or retry without penalty. Failing or fleeing takes you back to your last resting place, and these can be found across the archipelago. So while Tenderfoot Tactics expects a degree of engagement from you to get around and find your way, it’s also very forgiving.

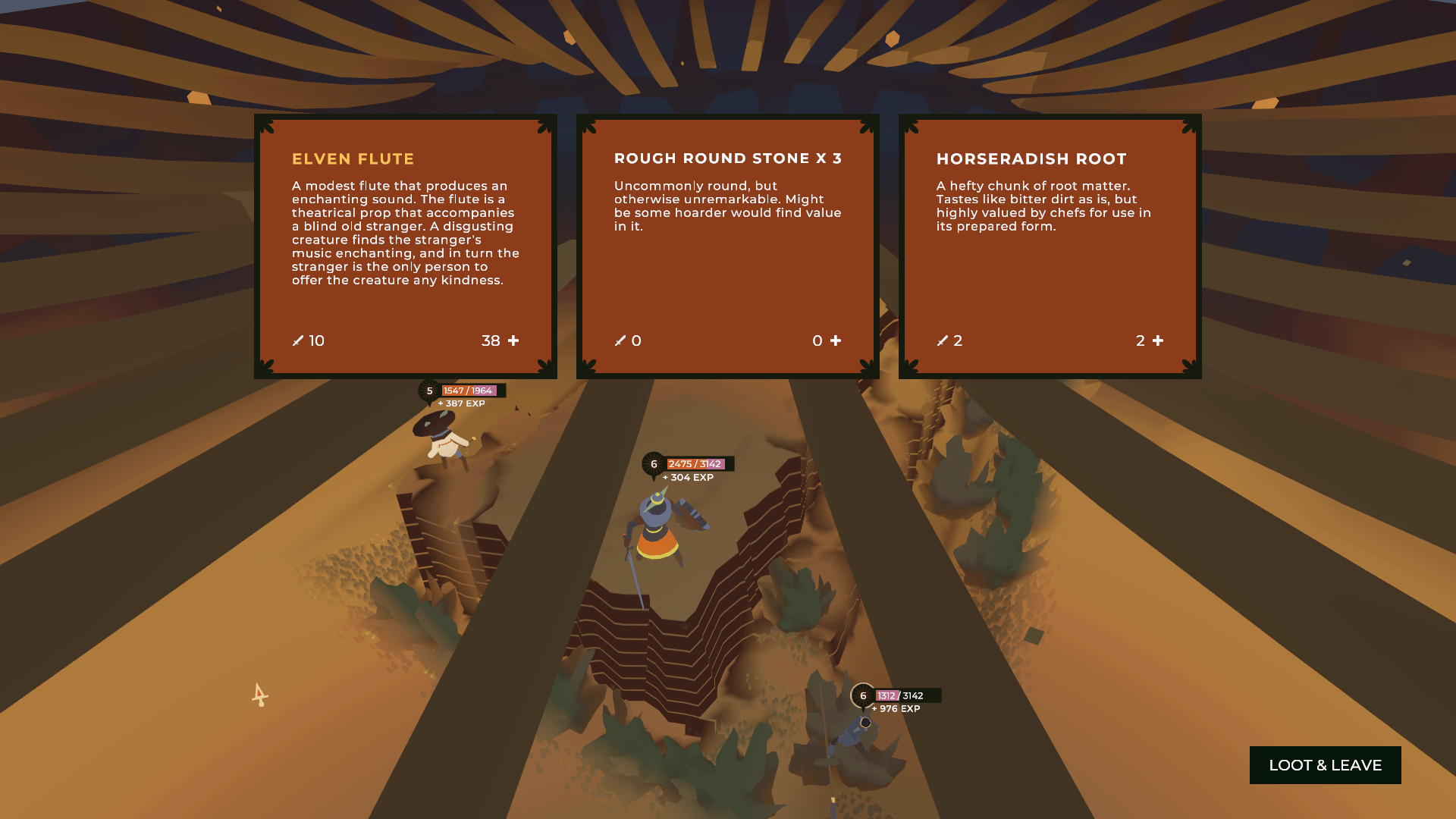

On your travels you can forage for mushrooms, herbs, roots, berries and other plants which double up as both accessories to buff your goblins’ health and power, and mordants and dyes to colour their clothes at town dyers. In some cases, they can be traded in for special trinkets. Battles score you loot too, from precious mineral fragments to rare artifacts.

Bird nests increase how far you can fly from your goblin band and the height of your bird’s-eye view, allowing you to see further.

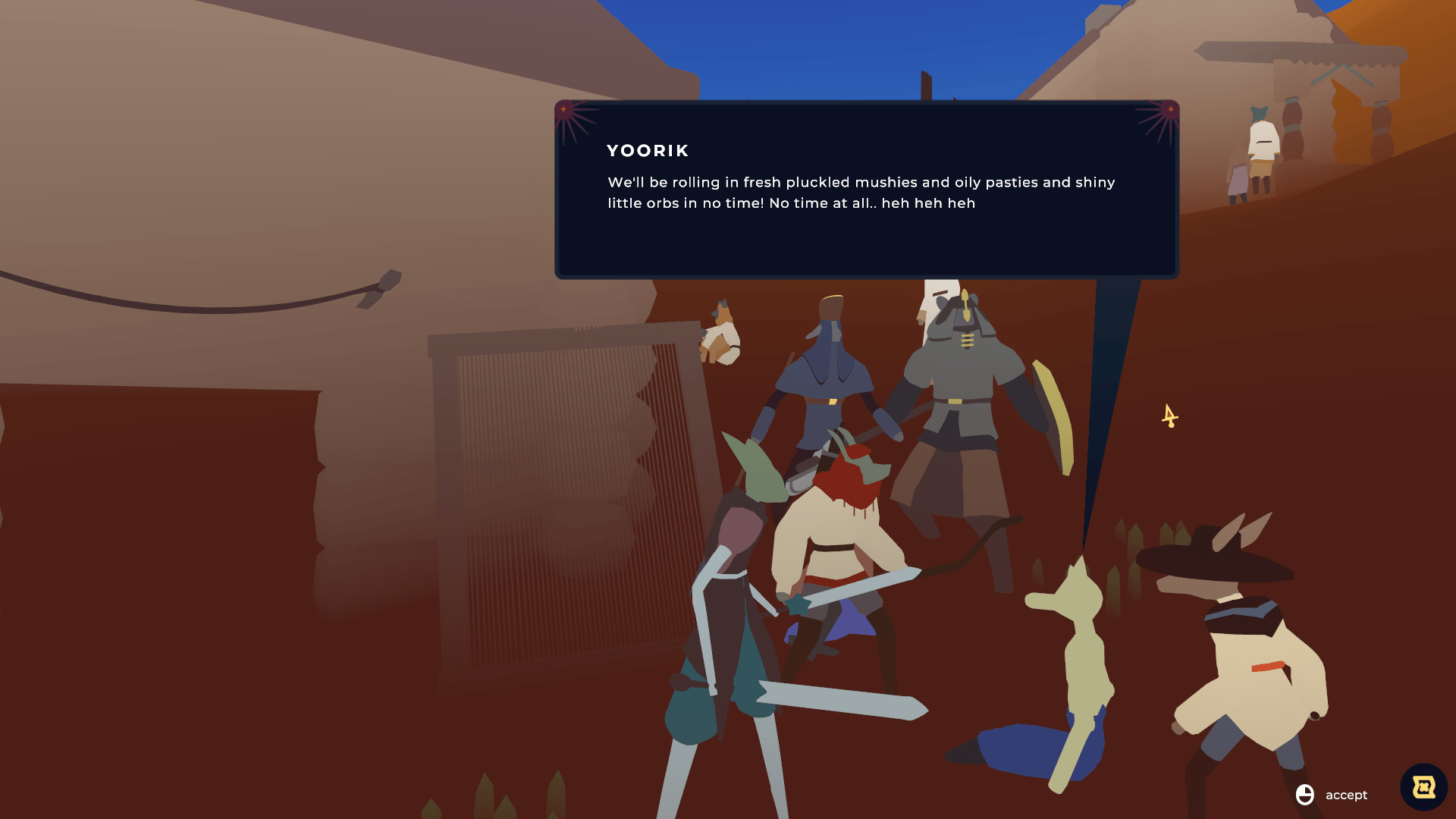

Certain items have special effects too, which pair up with skills in all kinds of interesting and powerful ways. Only two items can be equipped per goblin, but after losing my mind with XCOM 2’s fiddly item and squad management earlier in the year, I welcomed this. One of my favourite things about Tenderfoot Tactics is the delightfully flavourful descriptions that make up a large part of the game’s world-building. It was always exciting to pick up a new item:

Dotted across the archipelago are small goblin towns whose inhabitants don’t say a great deal, but, like the item descriptions, they’re entertaining, colourful and refreshingly odd. Some of the town names are great too, my favourite being ‘Hogglesderry’. Actually, it’s just my favourite town. The colours, the sounds, the music. And Stinkhorn Outskirts ‘slaps’ too. (how-do-you-do-fellow-kids.gif)

The towns are perhaps a little static for my liking, animated mostly by the sound design, but they’re still memorable. Towns are also home to hoard keepers who trade items based on your reputation with them. Reputation is accrued by freeing goblins from the fog and contributing items in return. Some goblins will even offer to join your team. I was surprised to discover that goblin towns can be taken by the fog, leaving them deserted and in a thick gloom. To push back the fog and restore the goblin folk, you have to defeat waves of enemies at a ‘fae tree’, which can be quite challenging. It’s possible to release one of your team as a ‘caretaker’ to protect the town, but for how rarely I returned (and for how fun the fae tree fights are!) I didn’t really see the point.

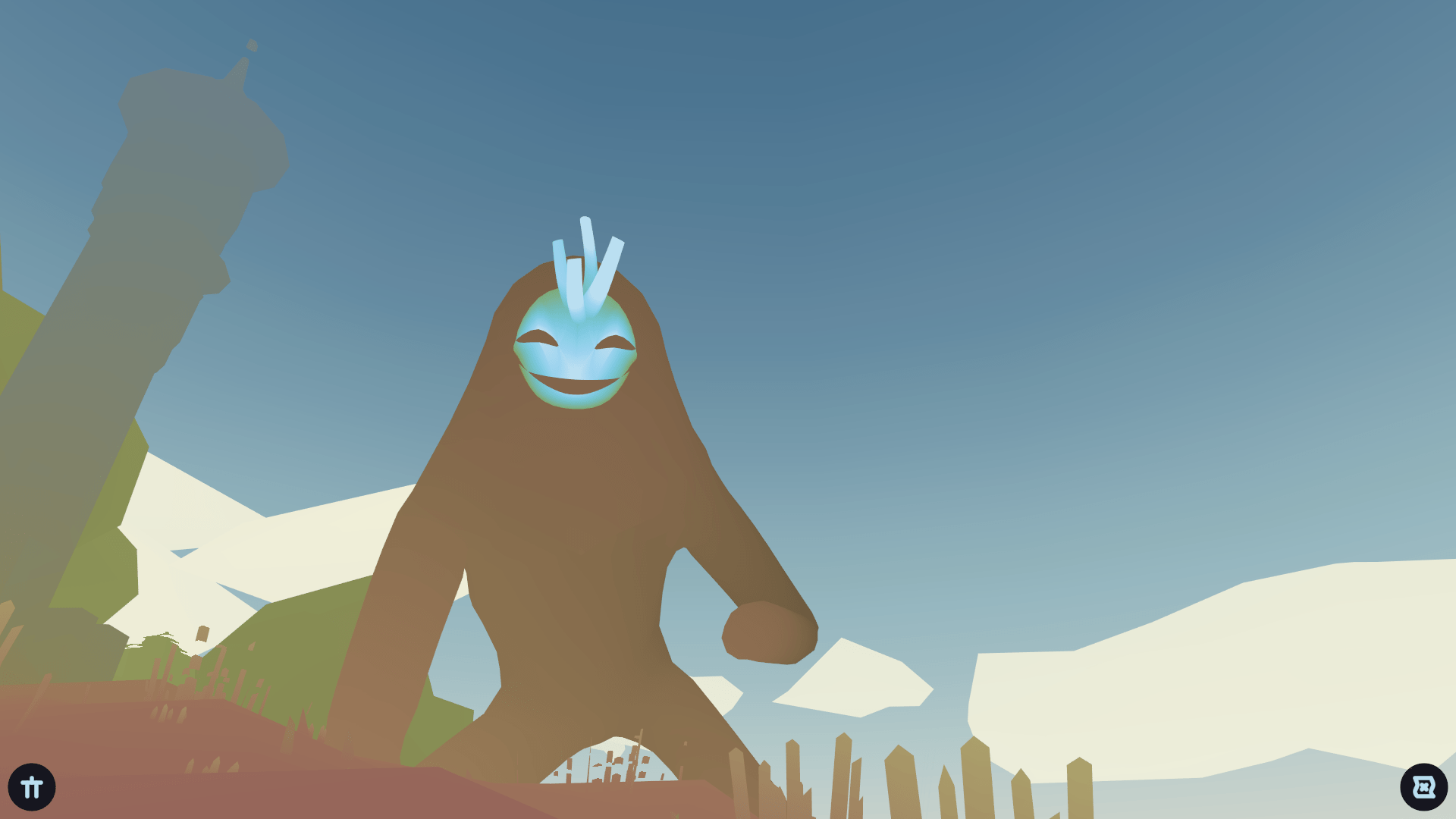

Out in the wilds of the archipelago you will occasionally come across towering Ghibli-esque spirits, unusual keepers of this strange land, who curiously watch over and talk enigmatically as you fight their own mobs of gobs. There are a number of unique and challenging set-piece battles in Tenderfoot Tactics that are among the game’s highlights for me. Some limit your goblin team size, some have awkward terrain to contend with (like deep bodies of water or enclosed lanes to fight in), some have waves of enemies that keep pouring in until you kill certain breeds, some have a set number of waves and a boss to fight at the end.

Tenderfoot Tactics isn’t a traditional game too concerned with telling a sprawling story with lots of dialogue, side quests, dungeons to spelunk and stuff to do. It doesn’t give you much, which, bizarrely, made me want to know more. I relished those weird little snippets of lore, spotting things in the distance and poring over maps to investigate doodles. What’s that skull there? What are those circles? What’s that I can see in the distance? Those kinds of questions always excite me, often more than the answers. But perhaps the biggest reward for exploring is the evocative presentation and feel of the world itself.

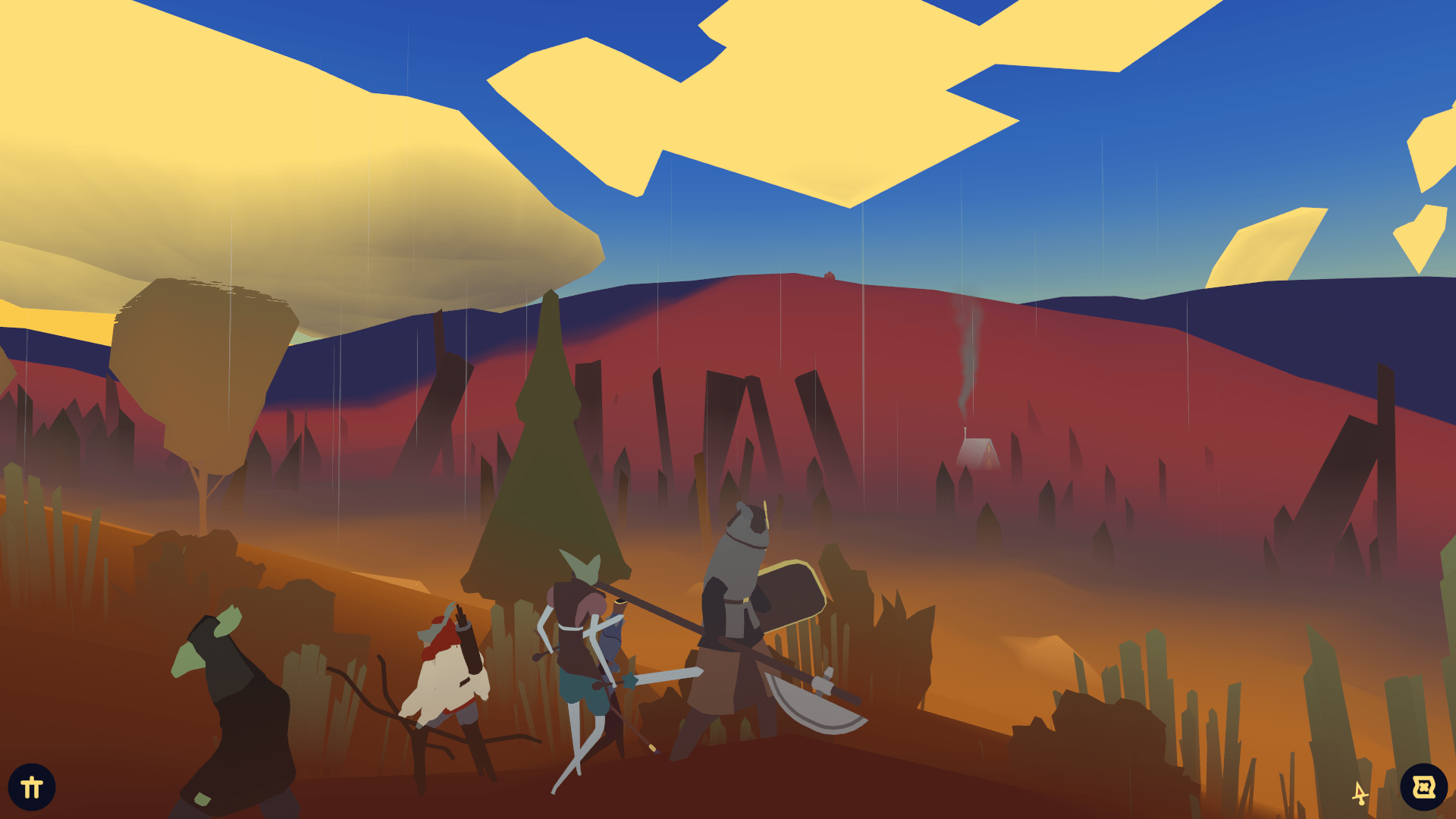

As you move through the archipelago, it hypnotically bubbles and undulates like a living painting, with bold impressionistic forms roiling around you. The striking colours frequently stopped me in my tracks as they shifted dramatically from one area to the next. Even the menu’s colour palette plays along. I took a lot of screenshots while playing, but take a look at it in motion. All the while, the sound design and music by Michael Bell complement it perfectly. When you’re in the fog or fighting, it’s heavy, dark and cold. The Battle for Bone Hill is nightmarish. Elsewhere it’s often breezy and downright lovely. Sky Lake is blissful. Everything here is playing in unison to create something that’s strange and otherworldly. (I also love the graphic design.)

For some, Tenderfoot Tactics’ minimalist open world might not be enough. I admired it for not being stuffed to the gills with junk to collect, boring folk to talk to and things to check off. It’s happy to give you a lot of (gorgeous) negative space to simply move through, to be curious and present in, punctuated by discoveries and full-blooded tactical battles. There’s a certain spark here as the game oscillates between that minimalism and the relative maximalism of the combat. Of course, it depends how much you enjoy either, but if you like the sound of navigating and exploring an unusual and beautiful place with plenty of chaotic but intricate turn-based shenanigans, then Tenderfoot Tactics might just be for you too.

![]()

Email the author of this post at greggb@tap-repeatedly.com