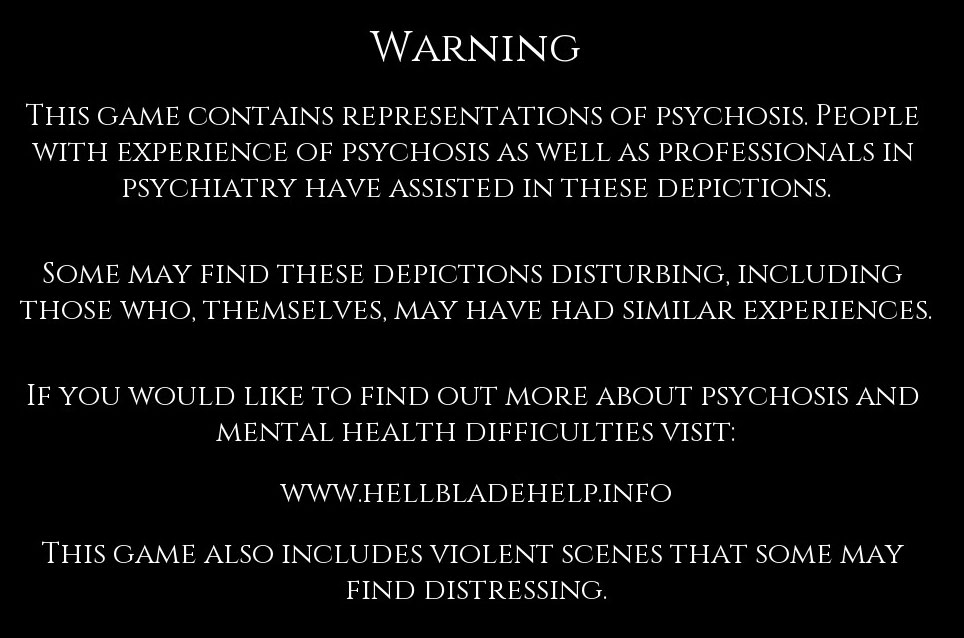

Up-front trigger warnings make me dubious. They often read like attorney-mandated ass coverage instead of any actual effort at sensitivity. I tend to mentally translate them into the most sarcastic, least considerate reading I can imagine. Thus in my brain, the one preceding Hellblade: Senua’s Sacrifice goes like this:

This game has crazy people, so FYI if you’re a crazy person or if crazy people make you sad. Also check out our website. Because hellbladehelp.info is totally what you’d visit to learn about mental illness.”

I mean come on. As disclaimers go, it’s not even comprehensive. What if Hell makes you sad? Or blades make you sad?

That’s an unfair reading, though, because Hellblade’s ridiculous disclaimer is well-intentioned. Ninja Theory demonstrates those intentions throughout its latest and best-yet project. The game’s primary mission is to depict the experience of psychosis, and it succeeds in this almost too well: there are times you forget that much of what you’re seeing or doing is tied to the protagonist’s madness, so in the moment you might not realize how elegantly the developers wove the mechanics of psychosis into the mechanics of the game.

An infuriatingly large amount of fiction dealing with mental illness is guilty of a great sin by suggesting it’s something the sufferer can overcome. Go on a transformative voyage, it says. Have an adventure, slay a “dragon,” and you’re cured. That’s one step away from advising mentally ill people to stop. Today, now, in the 21st Century, society still cleaves to such ignorant, tactless notions. “Instead of being depressed, be happy.” “Have you tried not hearing voices?”

Next time you run into somebody with cancer, ask them if they’ve tried not having cancer. See how well it goes over.

Hellblade does not do this, to its great credit. I had been worried its ultimate message would be that mental illness is correctable via Hero’s Journey. We’ve certainly seen plenty of games along those lines, even games I greatly admire, like American McGee’s Alice. But not Hellblade, which manages its message very well. It does not claim to provide solace or healing. It’s about creating the experience, and in so doing maybe helping non-sufferers understand better. To accomplish its goal, Hellblade must distinguish between itself as an external narrative and the more misguided perspective of its main character, which it does pretty well. Hellblade never suggests that the protagonist is going to get better. And indeed, she never does.

Whoops! Spoiler. Others below.

If we’re being flip and amusing, we’d write: Hellblade is the story of a nice lady named Senua who lives in Orkney and decides to visit Scandinavia on holiday, this despite not being over-fond of the Scandinavian people. The trip is partly a vacation – Senua is recently single – but as it happens, she also has some business in the region. So she paints herself blue, grabs a severed human head, and sets off. Hilarity ensues. She gets delayed in customs, loses her luggage (twice), has to borrow someone else’s stuff, becomes lost, and inevitably gets delayed by irritations from her past. Also her appointment does not go as planned.

If we’re being honest, we’d write: Hellblade is a primal scream of misery that lasts fourteen hours. Senua experiences horror, tragedy, and hardship beyond what any human could likely endure, plunged into nightmares and made to navigate them. It’s an intense, disturbing portrayal of a young woman suffering from major psychotic disorder. It’s horrifying. And the dreadfulness is multiplied by the player’s knowledge that Senua’s undertaking isn’t a grand quest but the product of psychosis. It might not be happening at all; in fact, it probably isn’t.

Senua is a Pict, an Iron Age people from Northern Scotland. The Picts are mysterious, though not a complete historical blank. Plenty of their artifacts are laying around. The language is lost, so we have no horse’s-mouth histories of them, but they got a lot of press from contemporaries. As a people, the Picts are maybe best known for being among the few to successfully resist Roman conquest. Eventually they were overrun and assimilated by the Vikings, which is the catalyst for the action in Hellblade.

All her life Senua has been tormented by voices and hallucinations. She calls it her “Darkness.” She thinks she’s under a curse. Her community thinks she’s under a curse. Hellblade is set around 900 A.D., a period notable for an absence of nuance, especially when it comes to sympathy for diseases of the mind. As cruel as Senua’s Darkness is, the cruelties inflicted by her peers are often worse. The one bright spot in this otherwise miserable existence is Dillion: her gentle, artistic lover, who displays kindness and compassion proportionate to everyone else’s vicious intolerance. One day while Senua is out for a walk in the forest, some Vikings arrive, raze her village, and treat Dillion to a gruesome ritual murder. The young warrior comes home to a village of cinders and a lover who’s been skinned alive.

A healthy person would probably go a little crazy under such circumstances too, but Senua is not a healthy person. Extreme trauma can trigger psychosis, and coming home to find your boyfriend flayed definitely qualifies as extreme. Senua, who’s already sick, is just pushed even further past the point of no return. She can’t live without Dillion and Dillion can’t live without his skin (if I recall, they also burned him alive after the flaying) and so that’s a conundrum. Senua is an optimist, though (not really) and she’s also psychotic.

A mentally healthy person would view skinned, burned, and dead as the kind of hard-stop complication that simply cannot be overcome. Senua, though, just confabulates: Dillion is dead, but the Gods can do anything. Since it was the Vikings who wrecked Senua’s town and killed her boyfriend, it’s to the Viking underworld of Helheim that she must go. Her thinking is that she’ll meet up with the goddess Hela, explain the situation, and ask for Dillion back.

Basically Senua conjures up the dubious notion that her lover’s death is reversible if only she can reach a customer service representative. Of course, Helheim does not have a return policy. Also the living are generally not permitted to visit. The growing chorus of voices in Senua’s head are adamant about these points, but her conviction is strong, so off she goes.

To the casual observer, watching a gameplay trailer or a commercial or something, Hellblade looks a lot like a cross between Dark Souls and the Tomb Raider reboot. In practice it has very little in common with either. The closest analogues to Hellblade are Ninja Theory’s own earlier games: Heavenly Sword, Enslaved, and DMC. I am on record as being a big fan of Ninja Theory. In my view this developer has gotten too much disparagement and never enough credit. Hopefully that will change, because Hellblade is its best effort so far, the most theoretically ninja game that Ninja Theory has done. It’s come close before (close enough to deserve better press than it’s gotten), but never this close.

It’s not entirely new territory for Ninja Theory. Hellblade shares similarities with the studio’s debut, Heavenly Sword, starting with the protagonist. Both Hellblade’s Senua and Heavenly Sword’s Nariko had difficult childhoods, highly developed daddy issues, and firm streaks of independence that spoke to their respective unbreakable spirits. Both find some degree of comfort in other outsiders, and both are chiefly motivated by an existential threat to their loved ones. The difference is that Nariko is angry and Senua is ill. Also Heavenly Sword is not about Nariko’s anger, but Hellblade is most certainly about Senua’s illness.

A project like this could fall into the trap of being dense and preachy. It could very easily stop being a game, dilute the experience by getting lost in exposition. After all, mental illness is a complicated subject. It is very hard to describe. If it had made this mistake, Hellblade would have been a failure. Instead, Ninja Theory managed the opposite: Hellblade is such a good game that’s it’s not unreasonable to ask if the mental illness stuff is necessary at all.

Ninja Theory has been criticized for using mental illness as a plot device in this game. It is not clear to me why that’s “wrong.” Technically everything plot-related is a plot device, right? If the implication is that its use as a plot device somehow diminishes the gravity of the subject, well, I disagree. Ninja Theory treats the issue with great respect and seriousness. Anyone who says otherwise has only to check out the included “Making of Hellblade” video. The studio went to great lengths to understand psychotic disorders and present them compassionately, which I appreciate. Moreover, Ninja Theory’s explicit objective was to provide the experience of psychosis. Director Tameem Antoniades has gone out of his way to emphasize that point.

Hellblade is not a treatment, or an infomercial, or a public service announcement. It’s a commercial video game. Interactivity makes games ideal vehicles for recreating experiences, especially ones that are difficult to describe. They don’t forfeit the right to make an entertaining game just because they chose to present this serious medical issue and put so much effort into getting the presentation right.

If you want to fault Ninja Theory for something, fault them for what they didn’t do, not what they did. What they don’t do is offer any clarity on what’s wrong with Senua. “Psychosis” is something you exhibit, not something you have. It’s not a diagnosis. Strictly speaking it’s not even a symptom, it’s a state of mind. So I found it rather odd that Ninja Theory uses that term exclusively. No responsible doctor would say “you have psychosis” and leave it at that. It would be the psychiatric equivalent of suggesting an Alzheimer’s patient’s disease is forgetfulness.

My guess is they did so to avoid unnecessary controversy. There are vast public misapprehensions (and professional disagreement) regarding mental illness and Ninja Theory probably did not want to get involved in the battle over DSM-V, for which I can hardly blame them.

But worry not! I did some sleuthing on my own.

A psychiatrist I happen to know listened intently to my description of Senua’s symptoms and offered a preliminary diagnosis: “something in the realm of schizoaffective disorders,” she said, “but I’d have to meet her to be more specific. Have her make an appointment. She should not be untreated with those symptoms.”

Then she said: “’Senua’ is an unusual name,” which led to a whole explanation that was uninteresting to her and expensive to me.

ANYWAY

The golden ratio for story-driven games is two parts experience to one part exposition. It seems simple enough until you actually try it, at which point the challenge of maintaining that balance becomes clear. The more complex the concept, the more difficult it becomes. Video games are best suited for fairly broad ideas and themes: a game about “madness” is a relatively easy proposition and we see them all the time. A game like this needs to get the granular stuff, and games overall want to avoid telling people things that can be shown (or better yet, experienced). With Hellblade, Ninja Theory did such a good job that they almost shot themselves in the foot. It’s ironic. The elements of Senua’s psychosis schizoaffective disorder are woven so deeply and so elegantly into the game that, in the moment, I sometimes mistook ingenious experiential design for irritating game mechanics.

Schizophrenics, for example, are often obsessed with patterns that only they can see (remember A Beautiful Mind?). Senua encounters locked doors marked with Norse runes. To open them, she’s convinced she must find matching patterns in her environment. Most games would have you looking for a bunch of little hidden tokens with the appropriate runes on them. Here, the symbols are literally hidden in the environment: the shape some tree branches make when viewed at the proper angle; the dapple of shadows on a longhall floor; a pile of broken furniture or the movement of a waterwheel.

When I got annoyed matching patterns, I would google them. Only later did I realize that Senua has no google; this is her life. Also, there are no locked doors. There are no secret patterns. She is not on a magical trip to Helheim to rescue her boyfriend, she is desperately insane.

Much of the game’s near-twenty hours are spent solving puzzles rooted in Senua’s hallucinations. Along with the aforementioned pattern-matching lust, she sees mirrors that reflect a world subtly different than the one she’s in. Gates that lead to other times or places. Strange order-of-operations challenges based on some shit she thinks she saw out of the corner of her eye. Faces hidden in rock formations. It’s really well done, assuming you don’t make the mistake I did and forget that all of this is meant to convey a mental state. The puzzles are almost never as devious as those found in Tomb Raider, but I was stumped a few times.

Amusingly, I’d assembled a new PC around the time I was playing Hellblade, and was very sensitive about “odd” behavior that might signify a problem with the build. Graphical glitches, for example, are a common tell that something is wrong. Stuff like abrupt color changes, inexplicable reflections, weird shadows, distorted textures. You know, the sort of visual aberrations common in psychotic episodes.

So during my time with Hellblade, part of me believed the PC was about to tits-up, while another part remained smugly convinced that it was all in the game. By the end I was so paranoid about Hellblade’s visual oddities I thought about triaging the machine and running tests. I nearly took my new computer apart because of Senua’s hallucinations. If that doesn’t say something about Hellblade’s effectiveness, I don’t know what does.

And then there’s the voices. Oh my god.

After the disclaimer about how Hellblade is a game and not a psychiatrist, there’s another popup that says you’ll get the best experience with a good pair of 7.1 headphones. THIS IS A LIE. It is very misleading and probably should be looked into, because what that popup should have said is surround sound owners, get ready to be FREAKED THE FUCK OUT.

Ninja Theory employed some terrifying, potentially actionable advancements in binaural sound recording for Hellblade, the result being that the voices in Senua’s head will make you shiver to your very core. They’re everywhere. They’re behind you. They whisper in your ear. They shout from far away. One will speak on your left while two others bicker with each other on your right. It’s most disturbing at the beginning, when you’re just paddling Senua along in a little canoe and the voices are weighing in on how ill-conceived and implausible this mission is.

Even later when you know to expect it, it can be hard. They’re relentless, those voices, they almost never stop talking and you can never tell which is which and sometimes they’re helpful as a preternatural early-warning system (“behind you!”) and sometimes they’re just messing with you on account of they’re cruel (“behind you!”). It is messed up, yo. I’m not even kidding.

Ninja Theory is one of three studios most commonly associated with “performance capture,” the others being Naughty Dog (The Last of Us, Uncharted) and Quantic Dream (Fahrenheit, Heavy Rain). In reality many AAA games employ performance capture to some extent, but those three are known for it, and in Hellblade it really stands out.

Realistic human movement is very difficult to animate by hand, so for years the industry has largely relied on motion capture: basically an actor or dancer performing certain movements on camera while wearing a “pingpong suit,” a funny unitard covered in little white sensors. Sophisticated software then maps the movement to 3D models so in-game characters walk and run and jump and stuff realistically.

Peformance capture is a more comprehensive version of that, capturing not just basic kinetics but the entire performance, dialogue and all. A big game can usually get its mocap assets in maybe 3-5 days of shooting; performance capture is like filming a thirty-hour movie, complete with stunts and blocking, so you’re looking at a 60-90 day shooting schedule easy. Performance capture rigs are much more elaborate, the assets much more complex, and the process much more expensive, but the payoff can be significant. No amount of mocap or animation can recreate the subtle tics, expressions, and body language of a real person; perfcap can – easily. Play The Last of Us or Hellblade for five minutes and you’ll be a convert.

Voice and performance-capture talent are wildly underappreciated in their own industry. There is no form of acting more physically and psychologically grueling. Twelve-hour days wearing a 70-pound camera rig that costs $100,000, dressed in a clingy suit that leaves nothing to the imagination, swinging from ropes and fighting with swords, three dozen pinhead sensors glued to your face, under searing 1600-watt Klieg lamps. And, of course, acting under these circumstances. But not just acting… acting entirely in the theatre of the mind, because your “set” is a greenscreen with only basic objects serving as frames of reference.

I can’t help but wonder if Melina Jeurgens knew what she was getting into when she signed on to play Senua. She’s Ninja Theory’s in-house video editor, and apparently does some acting and modeling on the side. Working with Ninja Theory, she’d surely have seen what goes into a performance-captured game, but seeing it and doing it are two different things. Jeurgens is not a professional actress, yet turned out to be an inspired casting decision. Her raw, physicality-drenched performance is amazing, laying Senua bare for the player from the very beginning. The role must have absolutely annihilated her voice, too: Senua spends the entire game screaming for release from the prison of her mind. Channeling the vulnerability and torment would have been no small feat for a seasoned performance capture artist.

Credit also goes to writer/director Tameem Antoniades, who has been around the block and knows what he’s doing. His camera and strong, coherent vision are clearer than ever in Hellblade. The emotionalism of the story, coupled with the need to portray Senua as both helplessly broken and highly capable, is an interesting directorial challenge that Antoniades met with aplomb. Antoniades and Ninja Theory are multiple-trick ponies – they don’t recycle the same character concepts over and over, instead building new layers on lessons learned from the past. Heavenly Sword’s Nariko is most decidedly not Senua, but there are elements.

It’s sort of interesting too to observe the character presentation Antoniades chose, transforming the (very beautiful) Melina Jeurgens into the (rather plain) Senua. Ninth-century Pictish warriors, especially crazy ones, realistically had bigger things on their mind than physical appeal, but video game developers often don’t. The ever-brilliant Jeurgens plays Senua almost without sexuality, focusing her performance on her mind and her capacity as a warrior. The result is that, even though saving Dillion is the crux of the narrative, we never sense that Senua has a strong connection to the real world. It creates more sympathy for an already sympathetic character, and by the end of the game we know Senua very well. That Jeurgens/Senua have the camera almost entirely to themselves throughout reinforces her centrality: none of this would be happening if it weren’t for this one person. Or, rather, none of this is happening, except to this one person.

Setpiece combat is sprinkled throughout Hellblade. There are no random encounters and enemies aren’t just prowling around looking for a fight. Each battle is a highly stage-managed affair, but even compartmentalized, the swordfighting manages to be among the coolest and most physically exhausting of any recent game. We’re dealing with monsters of the id here, which is important when considering the fights overall.

Historical evidence suggests that women warriors were quite common in Pictish culture. Not only does this mark out these woad-colored savages as being more highly evolved than America’s current president, it justifies the presentation of Senua as an experienced and perfectly capable warrior. Having no friends as a child means lots of time to practice, I guess. Combat mechanics are easily recognizable, requiring only a couple of buttons, but it takes a while to get really good at it. Once you do, the game amps up the challenge by turning some fights into an endurance run that can take twenty or thirty minutes to get through. It’s strenuous, but I never got mad at the combat – in fact I loved it and would have welcomed even more.

You’ll likely lose your first fight. It’s against an enemy type you’ll soon find hilariously easy to overcome, but everyone’s nervous the first time and you have no experience yet. Around that encounter, Hellblade breaks the fourth wall for the first and last time to make A Very Stern Announcement. It points out some black crap on Senua’s arm, stuff I’d assumed was a tattoo but no, and tells you that every time Senua goes down, it’s going to grow a little bit. Should the nottoo ever reach her head, it’s game over – your data will be wiped and you’ll have to start from the beginning.

Aieee.

Permadeath has its place in gaming, but you rarely see it in a game of this type. Even before I knew that Hellblade was a 10-20 hour game, I was anxious about the threat of having to start over. As gorgeous as the gameplay is, as great the performance and as exciting the combat, a lot of Hellblade is slow-paced, sometimes tedious environmental puzzles I was in no hurry to repeat. The longer the game proved itself to be, the more apprehensive I grew. Senua’s black arm-slime was also growing.

And there are ways to die other than combat. Senua is very much in danger of getting lost in her Darkness before ever meeting up with Hela, and her psychosis conjures up horrible experiences and horrifying memories fast and furious. You’re often chased by something you can’t see but know is right behind you. A single misstep and it has you. These moments get harder the further in you get, and there’s one part maybe 80% in that’s downright infuriating, when I died probably ten times in the span of fifteen minutes. Based on the arm-tentacle’s progress, I was like one micron from getting my legs kicked out from under me.

There’s just one thing though… it’s not true. At least, there’s no real evidence that any player has actually perma-died in Hellblade. Google has speculation both ways, but at the very least, it looks like the whole permadeath warning is nothing more than Ninja Theory toying with you, adding a very palpable element of stress that builds throughout the game, and reinforcing their intent at the same time.

Because how do you communicate the experience of psychosis? Maybe by telling you something in an incongruous manner, like a game that goes out of its way to never break the fourth wall suddenly doing so. Giving you information that you have no reason to doubt. A voice that only you can hear, a sign that only you can see. But to you it’s real enough, and it preys on you. And that stress builds and builds, and even when seedlings of doubt begin to grow – when, for example, you read an article that says “there’s no real permadeath in Hellblade,” you wonder… really? Are you sure?

Psychosis, after all, is defined as a mental state in which the sufferer is unable to reliably distinguish between what is real and what is not.

Anyone would look at Hellblade and assume it was created by a studio with 150 full time developers and a budget of $30 or $40 million. The combination of Unreal 4-powered environments, insanely detailed performance capture and stunning fight choreography mark it as one of the most striking games of the past year. It’s stable, playtested and largely bug-free, short but not super-short, featuring remarkable new technology and professional polish. It is, by all accounts, the very definition of what you’d expect a AAA game to be.

In reality, 20 people worked on Hellblade, not 150. Analysts estimate its budget as being south of five million dollars. That Ninja Theory accomplished all this with such finite resources is its own kind of crazy, and it has paid dividends. The studio has never had a runaway hit and its past games were expensive to make; it has the potential to reach Naughty Dog levels but has never been able to do so. To any publisher, allocating AAA resources to Ninja Theory would be a considerable risk. Allocating AAA resources to a game about mental illness – not cool mental illness but real mental illness – why, you’d be psychotic to do that. And in its own way Hellblade had to be made under these circumstances. $40 million would not have resulted in a better game, or a longer one. At best it would have resulted in exactly the same game, because Hellblade accomplishes what it set out to do and then wraps itself up.

I think there’s a certain inherent risk in portraying something like mental illness within the context of an entertainment product. No matter how sensitive the creators are and how seriously they take the subject, there’s always the chance that it gets trivialized by accident, a drive-by belittling. Hellblade has a lot of game-stuff in it: Picts and gods and hell and blades and magic and jumping puzzles and boss fights and so on. And aside from the disclaimer at the front, the truth is it could have been done without any of the mental illness elements. It could have just been an action/fantasy about a young warrior’s trip to Helheim and the adventures she has there. No one would have noticed. No one would have reviewed it and said, “what this game needs is for that protagonist to be mentally ill.”

Hellblade, unlike Ninja Theory’s other games, has been highly profitable. It broke even months ago and now stands at around 800,000 units sold, which is very respectable, especially for a game that cost so little to make. But I doubt it would have sold half as many units if they’d excised psychosis part.

Because, in the end, people are curious. And Hellblade does a good job – at times, too good – of presenting an experience that, thankfully, most of us will never have to endure in real life. Is psychosis trivialized? No. Do players come away with a better understanding of it? They very well might, but there’s a chance they’re enjoying the game too much to notice or retain its other message.

![]()

Note that Steerpike didn’t say what Senua’s Sacrifice was at Steerpike@Tap-Repeatedly.com.

Good read, Steerpike. It’s interesting seeing a different take on this game. To me, I saw it as significant parts reality mixed with Senua’s affliction. For instance, I saw her actively entering a hostile land where there were real people who wanted to kill her for the outsider invading their territory that she was. This was all colored by her “psychosis,” obviously, but that did not create the entirety of her journey. My read on it anyway.

I also do think the mental illness aspect of the game helped it immensely, and we wouldn’t have had a worthwhile game if it were stripped of it. Senua’s experience is so much more powerful with it, in that it humanizes her far beyond you’re usual video game protagonist fueled by needs for revenge for a lover’s murder. Without that element, it’s kind of a boring puzzle game with some exciting, but simple combat parts to it. Her anguish would have read more as cheap theatrics of a second rate video game actor, rather than genuine suffering. I believe Senua’s mental illness was the heart of the game (and not just a “plot hook). This is, at its core, a story about mental illness.

Finally, dude, put some spoiler tags earlier on this thing! I know the game has been out a while, but I have friends who visit this site who haven’t played it yet, and this is a game best entered with as little info as possible! 😉

I can definitely picture it as a sort of “Fisher King” situation along the lines of what you interpreted. Senua has perhaps gone to this distant place and maybe really is facing normal people, but doesn’t see them or her environment as they actually are.

Hellblade would have been a very forgettable game without the mental illness element, which is funny because it would have played more or less the same. Certainly its inclusion called more attention to the game (good in general) and humanized the character (good for the experience). It is funny to consider how Melina Jeurgens’ performance would have been judged if she’d played Senua the same, but there were no mental illness angle.

One of the most inspired decisions Ninja Theory made was to take a game concept about mental illness and center it around a ninth-century Pict. As I understand, the mental illness concept came first, and the gameplay/setting second; the setting they chose gave them immense leeway to be game-like with swordfighting and puzzles and even a little magic, but is a “gritty” enough real-world environment that they can also readily include their emphasis on the demons in Senua’s mind.

There’s a spoiler warning in there! All right, all right, I should be a little more up-front with them. I am covered in shame.

Hearing of Picts immediately makes me think of Robert E. Howard, specifically Beyond the Black River, one of his best Conan short stories in my humble opinion.

Anyway, Hellblade. This one is on my PS4 list but gads I can’t keep up with all the awesome exclusives…

And I hope Ninja Theory keeps making games for a long time.

Matt, your return to the long form is happily welcomed from this individual. Your take on Hellblade is insightful and funny, to say the least. I really enjoyed reading what you got out of the game, and I agree that Ninja Theory deserves immense credit for what they attempted and– I still think mostly– achieved.

I had also read that the permadeath thing wasn’t true, but I wasn’t willing to accept that and play carelessly as a result. I am a bit resentful though, if it was a ruse. If only because I wasn’t able to enjoy and absorb myself in the combat in the way I can in, say, Dark Souls — where I know there’s no truly permanent penalty. And like you, the thought of trudging through some of the puzzle sections for a second time was not going to happen for me. If there was permadeath, that would have been the end of my Hellblade story. In the end that black stuff got pretty high up my arm, but no permadeath. Still, I remember the combat poorly due to the stress of potentially failing.

I also agree that Juergens’ performance was inspired, especially for someone who was moonlighting as an actor/performance capture artist.

And the headphones…yeah, that made the game even more stressful. In particular, the whole Valravn section comes to mind.

As I said in my 2017-in-review, while I didn’t love the game I’m still encouraged to see games like this get made. Hellblade is like the AAA of AA games, and that’s a good thing for the industry in its current state to have, in my opinion.