Have you ever had a dream, Neo, you were so sure was real? What if you were unable to wake from that dream? How could you distinguish between the dream world and the real world?

Most children have a monster or two – under the bed, in the closet. One of mine lurked in the huge attic fan that cooled our home during the Time Before Air Conditioning. I never walked underneath when the slats were open. The creature was up there, perched above the rumbling mechanism. Go under and it might drop down and bury its claws in you. It could pass right through the spinning blades. I knew this. But I never saw it. Because there are no fan-monsters.

When we’re children, belief is much more powerful. For a child or a madman, just believing in something is enough to make it real. This is why parents never find the monster when asked to look. It’s not there because they don’t believe it is, but once they kiss good-night and exit the room, a frightened young believer is there alone. Click! goes the door, and then the monster is right back where it was, grinning, real as it ever had been. It’s just one of the rules of childhood monsters that go bump in the night. They are only real if you believe in them.

Another rule: they can’t hurt you (often can’t even see you) if you can’t see them. The monster is still there, because of belief, but screw your eyes shut and hide under the covers and you’re safe. That’s more terrifying than facing a monster, but it saved my life many times when I was small. Though if you’re like me at least once you chucked it all and threw the covers back and opened your eyes, knowing you’d die but needing also to know what the thing looked like. Just once, to get a look. And of course nothing was there.

Eventually we grow up, and something happens to damage our self-preservation instincts. When a grown-up hears a sound, do take the smart path and tremble under the sheets, eyes fiercely shut? They do not. We grown-ups hear sounds and we investigate. Because nothing’s going to scare a big fangy monster as much as a doughy fortysomething padding down the stairs in bare feet and kitten pajamas, feeling the way along with mole-eyes in the light of the modern candle, an iPhone forlornly glowing its lock screen.

The games of Ice-Pick Lodge have had a devotee in Steerpike since the beginning. This tiny Russian indie studio first drew worldwide attention with its 2005 debut, a surreal ingot of pure post-Brechtian desolation called Pathologic. A game about a squalid, forgotten town consumed by disease. So unutterably remarkable, in so many ways, Pathologic would have been even more acclaimed but for the fact that it’s basically unplayable. It’s dense, inaccessible, buggy, mistranslated, crushingly hard, and not much fun. This would be the beginning of a trend for Ice-Pick Lodge: brilliant, broken, strange games you have to force yourself to enjoy.

Next up was The Void, about which I have mixed feelings. It’s the most despondently sexy and disturbing game you’ll ever play, a hair more traditional and a bit more fun moment to moment, but just as inscrutable and a technical disaster. I played 2011’s Cargo! for about ten minutes before forgetting about it entirely, which may not be fair. It felt out of keeping with Ice-Pick Lodge, almost like they made it to prove they’re not who they are, but I didn’t honestly give it enough time to form such a complex opinion and I should revisit it.

In July of 2011, Ice-Pick Lodge turned to Kickstarter, asking a modest $30,000 to make Knock-Knock. An intriguing-looking game, even a blind man could see how the studio had reduced its ambition. Reputationally unable to secure funding for the million-ish dollar 3D games it had so far produced, Knock-Knock is a minimalist 2D scroller. The campaign was white-knuckled for a while, but a last minute surge put them over the top. People like me, people who understand and even accept Ice-Pick Lodge’s reputation but who nonetheless aggressively support everything they make, breathed a little sigh of relief. Gaming needs Ice-Pick Lodge.

In July of 2011, Ice-Pick Lodge turned to Kickstarter, asking a modest $30,000 to make Knock-Knock. An intriguing-looking game, even a blind man could see how the studio had reduced its ambition. Reputationally unable to secure funding for the million-ish dollar 3D games it had so far produced, Knock-Knock is a minimalist 2D scroller. The campaign was white-knuckled for a while, but a last minute surge put them over the top. People like me, people who understand and even accept Ice-Pick Lodge’s reputation but who nonetheless aggressively support everything they make, breathed a little sigh of relief. Gaming needs Ice-Pick Lodge.

Then we waited. Knock-Knock slipped past its estimated release. Backer updates grew rarer and more incoherent. Some got suspicious; others put it down to well-established Ice-Pickery. A couple weeks ago, pre-release copies started going to press (at which point Rock Paper Shotgun’s Jim Rossignol described the game as “completely terrifying… just [a] horrible brain-curdling sort of thing.”)

Knock-Knock, an odd, minimalistic existence-horror game of nightmares and fear and the thin membrane between us and the terrifying unknown, arrived October 4. I’m not exactly sure what about it took the studio two years, but it breaks the mold for them: a polished, playable game with reliable translation, Knock-Knock could almost be described as “accessible.” It’s also scary as hell.

Imagine a video game of Hughes Mearns’ eerie poem Antigonish. You’ve heard it somewhere. Remember? “Yesterday, upon the stair/I met a man who was not there/He was not there again today/Oh how I wish he’d go away… When I came home last night at three/The man was waiting there for me.” That one.

That’s Knock-Knock.

Here is a game about a mind left to its own devices that weaves a whole realm of nightmare and then locks itself in. It’s about a man who appears to be going mad, and it captures the vise of fear the onset of madness must bring, when the afflicted can no longer tell real from not, but senses he’s in danger of losing reality forever. This is not a survival-horror game, where you fear for your life. This is an emotional-horror game, where you fear for your sanity.

Like all of Ice-Pick Lodge’s work, Knock-Knock is smarter than it has a right to be, drawing inspiration from literature, art, and particularly Slavic folklore, which – if you’re familiar, Baba Yaga and such – is far more hideous than the western stuff. It’s very aware of its Russian pedigree, though its texture is less Russian than Ice-Pick’s other work, probably due to its solid translation. It’s pretty darn superb, and at ten dollars it hardly matters if your mileage differs from mine.

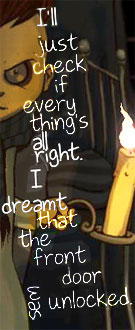

Deep in a sinister forest, the Lodger lives in a junk-filled house. He can’t sleep and he spends a lot of time afraid. The forest is ominous and his house is creepy and he’s all alone. At night he hears scary things, knock-knocking at his chamber door, and he worries the house isn’t secure. That something might get in. So he puts on his slippers and gets a lamp and goes to have a look around.

Basic but engagingly unique, it’s coy with feedback and reveals less than it withholds. Knock-Knock feels like its hiding something, like it’s acting functionally simple to throw you off. You move the Lodger through his 2D house, fixing and switching on lights in each room. Once you find a certain totem, he’s satisfied the place is safe and heads outdoors to check the forest. Eventually, fears put to rest, he goes back to bed.

The Lodger’s dreams then take him to another, darker house, more fearsome and seemingly more angry, because however macabre his waking home may be, the dream house is downright aggressive. The process is pretty much the same, though in the dream house if he stops and allows his eyes to adjust after turning lights on, sometimes he might get a message, or find a page of his missing journal, or maybe some new furniture will appear that he can hide behind. Here he’s waiting for time to pass, for sunrise, and his dreams are much more dangerous, at first, than his waking house. In his dreams, the Visitors are already inside.

When the Visitors come, there’s nothing you can do except hide and hope they lumber past without looking too carefully. The Lodger can’t do anything to fight them off. He doesn’t believe they can be fought off, so they can’t. The distorted mind of Ice-Pick Lodge founder Nikolay Dybowskiy is on full display here. He is one of the most gifted creatives working today, and I am so grateful I don’t see what he sees when I close my eyes. The Void’s nightmarish Brothers might’ve been created by a Bosch/Giger/Tesla collaboration; Knock-Knock’s more friendly, less hard-edged style is somehow a lot more threatening. And even though nothing’s traditionally “scary,” it will make your hair stand and your skin crawl.

Some Visitors follow child-terror rules, unable to see you if you can’t see them. When they do see you, something… happens. “Game Over” is rare (it happens, particularly close to the end), but there are penalties for being caught by one of those things. Avoiding them is not easy, and they’re not really bound by fixed rules. Just because one can’t see you, or can’t find you when you’re hiding, doesn’t mean the next won’t. Half of Knock-Knock takes place in a dream, the other half could be a hallucination, and in both the Lodger’s mind is coming apart. Nightmare structure extends to the house, which reconfigures itself every night. Should you find yourself cornered (and you will find yourself cornered), or discovered while hiding, it’s a Bad Thing. Sometimes Visitors will just materialize next to you. Unless it’s a pattern I missed, no rules are reliably the same moment to moment.

Don’tlookdon’tlookdon’tlookdon’tlookdon’tlookdon’tlook

As for the Lodger, with his sleep-erect red hair and gaping, sunken eyes, he has the fears of a child and the sorrows of an adult. The way he hides, cowering, his face covered with his hands, it seems so helpless. His haunted mein you get used to; the endless yammering not so much. The Lodger knows you’re there, and he talks to you. Way back to Pathologic’s beaky Executors, Ice-Pick Lodge has delighted in making games that know they’re games. The Lodger will look you in the eye and chatter in his odd subtitled Simlish. Sometimes wise, sometimes sad, often creepy, as the Lodger’s difficulty distinguishing real from not grows more pronounced, his demeanor changes. Near the end he plaintively whispers “Help me,” and you want to do what you can.

Time, and the fundamentals of Hide & Seek, are core themes of Knock-Knock. Time is what stands between the Lodger and the sunrise, and when you’re scared or in distress time moves like gelatin. Technically all you have to do in Knock-Knock is wait, because eventually time will pass. Totems scattered around the dream house speed it up.

Hide & Seek is a universal children’s game, and you’re playing with the Visitors, though they’re enjoying it more. If you hide from them, though, time moves backwards, erasing progress you’ve made. Should one see you, or injure you, you’ll lose gallumphing chunks of it at once.

Everything that might keep you safe has the capacity to increase your risk. Hiding reverses time, so you can’t do it for long. Lights take agonizing seconds to fix, and you’re often trying to do it as a Visitor is creeping up. Once on, they might banish the phantom… or they might just go off again. It feels safer to have them on, but the Lodger frets about night blindness, reasonably concerned that it’s easier for monsters to see in and harder for him to see out when they’re left on. It’s one of the many moments you wonder if the game’s suggesting one course of action when you should take another. What secrets or horrors might be revealed if you leave every damned light in the house glowing, attic to cellar?

Sometimes the Lodger decides to check the forest around the house.

In the dark. In his nightshirt. With a candle.

Not a Kalashnikov. A candle.

Initially, dreams are dangerous and the waking house is safe, but that changes. And you hit a point where the game essentially becomes timed. From then on there’s the possibility of getting on an irrevocable path to failure, which can be irritating if (like me) you make it to the very end only to realize you’d doomed yourself an hour earlier. Knock-Knock is going to take heat for that, and for moments of irritation when you suffer setbacks that aren’t your fault. Though its refusal to reveal anything is part of the charm and the design, it forces experimentation that often is meaningless since the rules themselves appear to change randomly. It can feel challenging for the wrong reasons, which is going to irritate some gamers. But nightmares are also like that, and that’s what Knock-Knock is.

Most of the time, little man.

It works most of the time.

There’s also the matter of minimalism. Knock-Knock is being ported to iPad and Android, and it feels like it actually belongs on those platforms. Though there’s more to discover than meets the eye, it’s a basic game that works largely because, despite the simplicity, it feels complete in most ways. I can think of a hundred mechanics they could have put in Knock-Knock but didn’t, yet I don’t find myself actually missing any of them. It’s also evident that they didn’t skimp on variety. The Lodger’s endless prattle and the notes you find laying around almost never repeat, and those things are what you’re playing to get.

Inscrutability makes Knock-Knock so interesting. You often feel like it’s toying with you, overplaying a ruse in the form of mechanics so uncomplicated it must be a smokescreen. Volunteering nothing naturally intimates vast stores of secrets. This is especially effective because Knock-Knock is so flabbergastingly basic. You just don’t – won’t, can’t – believe that’s all there is. It’s too simple to simply be that simple. Therefore it must be complex.

And to its enormous credit, maybe it is and maybe it isn’t. I certainly haven’t uncovered any trove of additional density, but I keep coming back, looking for The Rest, and don’t begrudge it. Even if there is no The Rest – and I’m guessing that there isn’t – that’s okay too. Simple or not, Knock-Knock is a fairly fun game to play. It feels… done. Like I said, it could’ve come with a million other gewgaws. Traps to set for monsters! A fusebox in the basement! Multiplayer deathmatch! Objects of use throughout the house! But no. It has none of these things and is right not to.

Really Knock-Knock is a bit of a red herring. It’s a game where the game is discovering that there’s no more game. The revelation might be irritating until you realize that the game you played was just fine.

I hate to be negative, but I don’t know that locking the door is going to help.

There’s nothing mainstream about Knock-Knock, it’s far weirder than most games ever dream of being. And it does feel very much like an Ice-Pick Lodge game. It’s creepy, disturbing, packed with imagery that will make you shudder. It’s written in a prose style both haunting and impressive in the scope of its control over language. It has a fair number of irritations, but my overall verdict is pretty positive in spite of them. It may not be as memorable as other Ice-Pick Lodge work, but it’s a lot more playable.

Nikolay Dybowskiy has never denied the shortcomings of his studio. Instead, he insists that they’re perfectly adept game designers… they’re just game designers who happen to view gameplay as an obstacle, something that interferes with the artistic creation they’re interested in producing. That gameplay goes in at all is a grudging acceptance of industry reality, and naturally they don’t put much effort into it. “Gameplay is dumb” is a weird thing for a game developer to say. But then, Dybowskiy has always been an iconoclast, and he’s certainly a genius. For the man who gave us Pathologic and The Void, we can tolerate some oddities.

Knock-Knock is brief and too simple, though if it were longer its simplicity would hurt it more. It often feels like you’re not playing a game, because it doesn’t seem structured like one. It’s more a horror activity than a horror game. I think in the end it will not be remembered as canonical Ice-Pick Lodge work; it may not be utterly forgotten like Cargo!, but it doesn’t have enough facets to be studied relentlessly or endlessly revisited. As horror it delivers uniquely. I avoid horror games, to be honest. I’m a scaredy-cat. So I appreciated that Knock-Knock’s approach to horror is very different from the anticipatory dread most employ. Will some people complain overmuch about the brevity and the minimalist mechanics? Yes, and not without cause. Some people will feel ripped off by the game, as some would feel ripped off by Pac-Man today. Despite very modern aesthetics, Knock-Knock often feels mechanically like it’s from an earlier time. But you know what? Big deal. It’s ten lousy bucks. Nobody’s trying to pull a fast one on you – I spent $60 on The Bureau, a far less impressive game overall, and yet I’m hearing more whining about this fascinating indie game from a fascinating indie game developer.

Asking for thirty grand to make a video game is low-end even for Kickstarter, yet they only just scraped through. That tells us how much their reputation has hurt them, that they’d struggle for $30,000 even as wholly asinine concepts like the Ouya console raked in a hundred times as much. I’m afraid that Ice-Pick Lodge will always be at subsistence level, oblivion always near at hand. Knock-Knock isn’t going to change their position, either – hopefully it’ll do okay, but it’s not going to be a runaway hit. It should allow the company to continue its existence, though, and hopefully get started on something new and weird and exciting.

Not many hand drawn 2D scrollers could make your bones tremble and your skin want to pack up and move away to some sunny spot on a beach, far from haunted forests and dark nightmares and stunted, candle-bearing bachelors. It’s a fun game, and a smart rumination on the metaphysics of terror. It asks disturbing questions, sometimes directly, as all Ice-Pick Lodge games do. What would happen if you ran into yourself? in a chat room, in a dark alley, at the store? Just… you. Though un-sinister on the surface, it would shatter in a stroke the whole of your world view, and bring about a gnawing revelatory terror. What if I am not me? What if you are not you? You don’t see that kind of philosophical horror in Dead Space, and so Knock-Knock feels fresh, intriguing, and even magnetic.

I kind of feel like playing it right now. You should do yourself the same favor.

![]()

Knock-knock. Who’s there? Steerpike’s email address.

I have played this game, am currently up to the point where the white fracture appears (should be a very non-specific spoiler hopefully). I think I understand what you mean by it becoming timed, and I rather dread that possibility. Really good design though.

Indeed, Callum, keep an eye on that thing. I had a run of bad luck shortly after it appeared, and things went south pretty quickly. Good luck!

Wow, this looks really good.

Judging from the trailers, such bad runs happen quite a bit. And I am not an instinctive hider.

I should set some time aside and really do some sort of Ice-Pick month next year.

Oh boy. Me too. I’ve still not finished the Void or Cargo, or even played my installed copy of Pathologic.

Same here. My Pathologic just sits there, waiting.

Pathologic… it’s so remarkable. And at this point I think anyone who tries it will be going in with their eyes open. When I bought it, in the wake of John Walker’s Eurogamer review, I had the then-fashionable “maybe it won’t be as broken for me,” worldview. This worldview is not effective. It will, in fact, be as broken for you.

Yet despite being unplayable, it’s playable. I don’t recall it crashing or anything. The “broken” manifests in other ways. And to some degree, the “broken” stems from the game’s abject refusal to give you any guidance or feedback. In fact, it overtly lies to you. We’re used to certain feedback mechanisms, even in hard games. Ice-Pick Lodge doesn’t do those feedback mechanisms, period. I’d pay good money to read Harbour Master’s and/or ShaunCG’s views on it.

Maybe we should organize a Patho-laythrough on the Tap forum. Since you have to finish three times to uncover all the secrets and I only finished as one character (plus I’ve forgotten so much) it’d be practically new for me as well.

It’s a horror game, they said. It’ll be fun, they said.

I got owned by a BED. How does a bed find you when you’re hiding behind something? IT’S A BED. Plus how can a bed get at you when you’re crouched behind a dresser? I call bullshits on that one.

Also yeah I ran out of time and went nuts, apparently. You win this round, ghost bed.

Yeah, it’s not just a bed, it’s an Evil Bed. Well, the ghost of an Evil Bed. Those things’ll light you up, man.

I’d never heard the middle verse of Antigonish before. Holy carp.