I remember well the first and only time I saw Roman Polanski’s Repulsion. It was back in film school, in my Subjective Camera course. I will never see it again.

“You will see a woman who is going mad,” said Professor Bauland. “You will see the world as she sees it, you will see the walls of her reality literally crack.”

I try not to think about Repulsion very often, because it’s one of those small handful of films I found so disturbing, so unsettling, that even now years later they can cause a chill. Movies about madness tend to unnerve me, from Session 9 to Jacob’s Ladder, and I often avoid them, even though some of my favorite films include madness as a main theme.

![]()

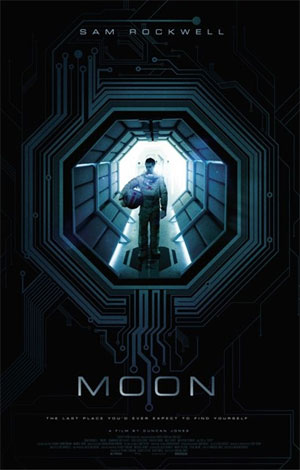

I bring this up because I saw Moon recently, on my brother’s recommendation. It’s a 2009 science fiction movie directed by David Bowie’s son Duncan Jones, and it is really, really good. Really good. Featuring Sam Rockwell – one of the best and often misused actors of his generation – and a disembodied Kevin Spacey (one of the best actors of his), it’s the story of a fellow who works, alone, on an energy gathering base on the far side of the moon. His only company is a servicebot (voiced by Spacey), and as the film begins, his three-year contract is coming to an end. But the communications satellite to earth has been on the fritz, leaving him with only pre-recorded contact with other people for quite some time, and the loneliness is beginning to crack him up. Slowly, slightly, subtly. He sees things; nothing threatening, just… out of place. He hears things. He has bad dreams. He wants to go home, but he’s not bouncing off the walls. And then something happens that really turns his moon upside down.

I bring this up because I saw Moon recently, on my brother’s recommendation. It’s a 2009 science fiction movie directed by David Bowie’s son Duncan Jones, and it is really, really good. Really good. Featuring Sam Rockwell – one of the best and often misused actors of his generation – and a disembodied Kevin Spacey (one of the best actors of his), it’s the story of a fellow who works, alone, on an energy gathering base on the far side of the moon. His only company is a servicebot (voiced by Spacey), and as the film begins, his three-year contract is coming to an end. But the communications satellite to earth has been on the fritz, leaving him with only pre-recorded contact with other people for quite some time, and the loneliness is beginning to crack him up. Slowly, slightly, subtly. He sees things; nothing threatening, just… out of place. He hears things. He has bad dreams. He wants to go home, but he’s not bouncing off the walls. And then something happens that really turns his moon upside down.

Moon is not a movie about madness in the traditional sense that Repulsion is, and it’s not a disturbing picture at all. It’s just really good, redolent with homages to 2001: A Space Odyssey and even Alien to some degree, though not in the aliens-eating-faces sense. Moon is about how space is big, and how the moon is big, and how lonely things must get out there when all you have to do is your job, and all that inky blackness between you and anything you might consider home. It does a few very unexpected things, this film, and it keeps you guessing as to whether Rockwell’s character is in fact losing his mind or there’s something else going on. Without spoiling it, I’ll merely say that I’d have preferred Moon ended differently, but even that minor subjective issue isn’t enough to drain my regard for the film. It’s really excellent.

Repulsion, meanwhile, is also excellent, but it’s a horror film as much as a psychological thriller. Once again you’re dealing with a character who’s on her own, this time in a 1960s London flat she shares with her sister, who’s jetsetted off to Italy with her boyfriend. Catherine Deneuve plays Carole Ledoux, a young woman who comes across as a bit “off” from the very beginning, but spirals into complete psychosis without her sister there to support her. The walls crack, and hands reach from within to grasp her as she makes her way down the hallway. She is tormented by paranoia, even hallucinating a terrifying rape at the hands of an imagined intruder. This in turn leads her to react violently to more well-meaning visitors; she bludgeons one to death with a candlestick and throws his body in the bathtub, then slashes her landlord to death with a straight razor. By the time her sister returns, Carole is catatonic under the bed, and the flat is in shambles, with corpses in various stages of decomposition, food rotten on the countertops; basically total ruin. I found the film very unsettling, as Carole’s descent into madness was so sudden: a fragile girl, obviously, and one repelled by the touch of other people, left alone for just a few days and reduced to feral psychosis.

Session 9 was another like that, this one a film about asbestos workers clearing out an abandoned asylum. One, more a slacker than the others, comes upon some old tapes of interviews with a murderer who’d been committed there years before. This killer suffers from Dissociative Identity Disorder – what used to be called multiple personalities – and talks at length about the different characters that live within him. One lives in the eyes, he says; and one in the legs, and so on. Only in the final tape, after all hell’s broken loose among the men working in the sanitarium and one of them is killing the others, is another personality revealed. Unlike the first few, though, this one warns of a dark creature lurking in all of us, ready to strike when we need someone to do what we cannot bring ourselves to do.

“Where do you live, Simon?” asks the psychiatrist.

“I live in the weak, and the wounded,” the personality replies.

Again, it’s a film where you spend a lot of time guessing. Who’s the killer, why’s the killer killing, is this place haunted, why do these guys have such tension among them, etc.

Anyway, I’ve come to think about madness in games, and how it’s presented. We’ve seen very few “sensitive” presentations of mental illness in games, and in videogames where the madness is supposedly part of the experience (games dependent on the Cthulhu mythos, for example), we’ve never seen developers really take innovation and run with it. Call of Cthulhu: Dark Corners of the Earth, a game that suffered so much throughout its development we’re lucky it saw the light of day at all, promised an interactive sanity system that was not based on menus or HUD items. Basically, if you were going crazy, it showed you shit. Maybe that shit was real, maybe it wasn’t. Up to you how to react to it. And there were moments in Dark Corners of the Earth where that sanity mechanic could wrap icy fingers around your heart – I remember one time I found a little girl down in the sewer. She splashed off before I could get to her, but it haunts me to this day whether I really left a child alone in a sewer or whether I’d imagined the whole thing. Most of the time, though, Dark Corners of the Earth contented itself with just blurring your vision really bad when it wanted to make you feel like you were losing sanity. That got kind of irritating.

Anyway, I’ve come to think about madness in games, and how it’s presented. We’ve seen very few “sensitive” presentations of mental illness in games, and in videogames where the madness is supposedly part of the experience (games dependent on the Cthulhu mythos, for example), we’ve never seen developers really take innovation and run with it. Call of Cthulhu: Dark Corners of the Earth, a game that suffered so much throughout its development we’re lucky it saw the light of day at all, promised an interactive sanity system that was not based on menus or HUD items. Basically, if you were going crazy, it showed you shit. Maybe that shit was real, maybe it wasn’t. Up to you how to react to it. And there were moments in Dark Corners of the Earth where that sanity mechanic could wrap icy fingers around your heart – I remember one time I found a little girl down in the sewer. She splashed off before I could get to her, but it haunts me to this day whether I really left a child alone in a sewer or whether I’d imagined the whole thing. Most of the time, though, Dark Corners of the Earth contented itself with just blurring your vision really bad when it wanted to make you feel like you were losing sanity. That got kind of irritating.

I’ve made well known my feelings on Alice, a game that ruminates heavily on the issues of sanity, but Alice is not exactly a game about madness. It’s about the consequences of madness, about how Alice’s own tragedies led her mind to shut down. It does a wonderful job of using Carroll’s literature to construct a diseased version of a teenage girl’s mind in a somewhat… this may sound odd, but in a somewhat realistic way. Most games that use insanity don’t really meditate on the horrors of mental illness, and it’s something I’d frankly like to see done more. Games are all about the mind, really, and though we seek them for entertainment it seems to me that they would be a good avenue for understanding the darker corners of the misunderstood human psyche. Experimental titles like The Chinese Room’s Korsakovia and Dear Esther toy a lot with putting the player in the shoes of someone who has gone mad, removing the anthropomorphic signals and general tenets of reality that we depend on to define whether we’re in the real world or lost in the labyrinths of our mind, while the Silent Hill series and Alan Wake, both steeped in survival horror, still manage to show us the potential of insanity in videogames without ever going as far as they could to really flesh it out.

That insanity and horror so often go hand in hand in games is telling. There is a strong argument to be made that the greatest fear isn’t of losing one’s life but of losing one’s mind, to be lost forever shrieking in a cold world where awareness and reality don’t match the patterns we know and depend upon.

I found Repulsion so disturbing, I think, because it was telling a story of a woman who had always been sick, but who had managed somehow to get by in life until something snapped and the walls of her reality came tumbling down, with tragic results. Moon makes the viewer question what is real while offering a glimpse of hope and freedom from the solitude in the form of that soon-to-be-expired three year contract. Games, which we can enter and leave at will, seem a proper avenue for understanding more clearly what the mind can do when it goes to dark or cold or strange places, and it seems avant-garde developers would do well to explore those places with even greater commitment to understanding the human drama of the mind.

Stories of madness tend to frighten us because mad people don’t know what is real and what isn’t, or even if they’re going mad. John Carpenter’s In the Mouth of Madness, another film I enjoy, follows a most-decidedly sane man through a journey that leaves him wondering whether anything at all is real, and posits the idea that reality itself could be molded by a storyteller with sufficient power over his audience. “More people believe in my books than believe in the Bible,” says Sutter Cane, the author who has figured out that so many people read his schlock horror novels that he can actually modify reality simply by writing something in one of them. “Did I ever tell you that my favorite color is blue?” He playfully asks the protagonist… and in the blink of an eye, the whole world is blue. By the end of the film, the see-it, touch-it groundedness of Sam Neill’s protagonist has been so warped that he actually seeks out the movie version of Cane’s latest book, knowing it will drive him mad… on the not implausible logic that in a world of insane people, the only truly dangerous thing to be is sane.

It would be interesting to see any of these movies see a complement in the world of games. Not just haunted asylums and villains who are crazy because that’s a convenient way to justify their various excesses, but stories about normal people losing their minds. It is, after all, one of the most tragic and disturbing stories that can ever be told. Perhaps by playing some of these experiences, people will gain a greater understanding of, and sympathy for, people who suffer mental afflictions, people who are helpless but bear no obvious marks. The same neurotransmitters and pathways responsible for the transmission of physical pain are responsible for emotional suffering as well; this is why depressed people so often seek out chemicals that make them happy, however briefly, however unsafely. When physical pain is a problem, you scream. Emotional pain and mental illness have just as many screamers, but the screams are not heard. Perhaps games could be part of the great educative force necessary to bring more understanding to the human mind, and finally start to treat mental afflictions correctly.

Email the author of this post at steerpike@tap-repeatedly.com.

[…] thought Steerpike’s post about Madness as presented in cinema and in games was asking all the right questions but offering precious little […]

Great article Steerpike.

An aside here: A great movie about insanity and split personalities that doesn’t go “crazy” trying to make its point is Peacock. I saw it with Jen and Raj and Heather. Made a couple of years ago, its about a quiet man living in a small town. He has a split personality, one a man, one a woman and they are married and battling constantly to dominate the body they are trapped in together. It is a haunting study of one person’s ever increasing insanity and how they come to terms with it. Highly recommended. (I might even write a review about it soon).

Interesting point about the neurotransmitter pathways being the same for pain and emotional suffering. I didn’t realize that. Emotional suffering can be tremendously more damaging than physical pain as it seem to transmit endlessly.

I love the topic of madness.

Another movie related aside:

The atmosphere, the feeling of oppression and of being driven into insanity in films by Roman Polanski is something incredible. My favorite is probably The Tenant which is probably the only film that I was at the same time completely terrified and not able to stop laughing. As crazy it may sound. 😉

Great article – I think Solaris is a great look into the human psyche as well. One thing I liked about the Daniel Craig ‘Bond’ reboot is that the take on Bond is that he’s ‘damaged’ goods, which is why he does what he does. He’s no longer seen as the idealistic male, but as someone who essentially is driven to a flat-affective state by the trauma he’s suffered watching loved-ones die. I almost pity the new Bond, rather than seek to emulate him or his lifestyle.

Sam Rockwell is a great actor – did you see him in Confessions of a Dangerous Mind?

Sorry, preemptive and obligatory comment:

Moon was absolutely incredible in every way.

Edit: (My only gripe with it is highlighted by Meho in the next article but to me that wasn’t anywhere near a big deal.)

I liked Tarkovsky’s Solaris very much, Jarrod – the Clooney/Soderberg one less so, though my brother (who recommended Moon) tells me I should give it another chance because he really enjoyed it, so I mean to do that sometime soon. I thought about mentioning it here. Another favorite of mine is The Game, in which the character just isn’t sure whether he’s going nuts or something’s going on around him.

Oh yeah, The Game was awesome. I’m not sure if Fight Club should be included here – but it was a formative movie for me in its day.

I need to check out Tarkovsky’s Solaris, which you’ve mentioned before, but I may be tainted by Clooney’s/Soderberg’s and may not appreciate it as much as I ought to.

I enjoyed Moon, despite going into it thinking it was a psychological suspence. I justified it by looking at how Sam’s character(s) dealt with their situation and faced their impending and unavoidable fate.

I should warn you, Jarrod, if you haven’t seen a Tarkovsky film before, you might want to prepare yourself. Tarkovsky was a believer in what he called “sculpting in time,” a technique everyone else calls “taking an absurdly long period to accomplish what a single three-second shot could accomplish.” And Solaris does have the most egregious example of this: a 20-or-so minute, unbroken, first-person shot of driving through Moscow traffic.

The movie’s brilliant, but you can go ahead and fast forward past this segment without missing anything, once you’ve seen enough to establish that an inconsequential and never-reappearing character is, in fact, driving through Moscow traffic. Just FYI. 🙂