It was with no small amount of relief that I decided not to write this piece as a review. At first I thought maybe I would, but I realized, quickly, that I might not like what I had to say in it – not always. Not everything.

“This story, like all good stories, begins where it ends…” – Lady Alvane

Dreamfall Chapters releases, finally, on October 21st. Eight years feels like a very long time to wait for a sequel, especially when that sequel was announced in 2007. It is technically a sequel to Dreamfall, I suppose, which released in 2006, after an also-fairly-lengthy gap of six years since The Longest Journey. I was fortunate enough to come to The Longest Journey late in 2005, when it was already something of a modern classic, and so I didn’t have long to wait for the first sequel to my new favorite.

If I were to really review The Longest Journey, or even do a Revisited on it, I would want to do so from the perspective of the person I was then, in my freshman dorm in the fall of 2005. I didn’t know a lot of people yet, aside from my roommate, who went to the same high school as I, and a few people on our hall, including one guy who recognized The Longest Journey easily when passing my room one day, and also later showed me the first episodes of Arrested Development I ever saw. So I’m saying he had good taste.

The person that I was then, who had schlepped his PS2 to college in case there were some JRPGs or Ratchet & Clanks or Jaks or Sly Coopers that needed playing, fell in love with The Longest Journey immediately in a way that he – that I – had rarely fallen in love with a game.

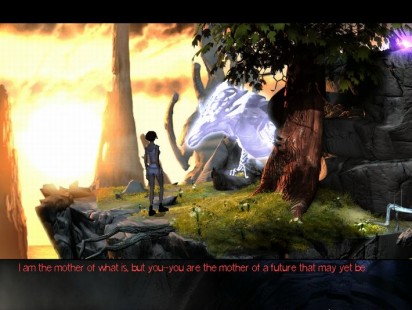

“Unlike you, we accept our destiny.” – Spirit of the Trees

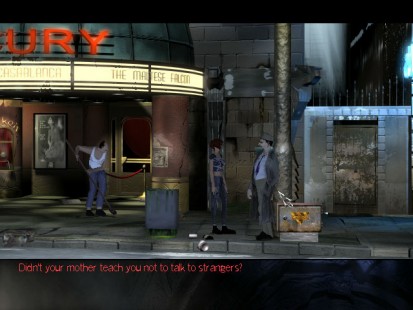

It is the early 23rd century and April Ryan can’t get a good night’s sleep. She has these dreams – vivid, troubling – of fantastic landscapes, of tree spirits, of dragons; of something nightmarish and dangerous. The weirdness increases. April struggles to finish her art project, due as part of her studies at a prestigious art institution. Her dreams become waking. Cortez, the neighborhood’s resident eccentric, tells April she is special and has a destiny. Other people see what April had been calling “dreams.” Cortez, a Cryptic Old Man who prefers the world in black and white, “like all good movies,” starts April down the path of fixing things.

He sends her to another world.

There are two worlds, you see: Stark, April’s world, our world, albeit a few hundred years from now, a place of science and logic and apparently unsubtle names, and Arcadia, a world of fantasy, where magic exists and chaos, of a sort, is the rule. They exist in parallel, each only visible to the inhabitants of the other in dreams. Each in grave danger.

“Your journey began with an answer. It is only now that you know the question.” – the Blue of the Kin

There are ways, I realize now, in which I am April Ryan. I wasn’t then, oddly: I could appreciate her depth and complexity and acknowledge her as, even now, one of gaming’s best female protagonists, but aside from being very close to her age I don’t know if I had a lot in common with her. I hadn’t had time to become disillusioned with my career path since I hadn’t really made a choice yet; I didn’t know creative dry spells the way I do these days.

I guess I’m saying I could comprehend, if some high strangeness fell in my lap next week, chasing after it despite my outward misgivings. April refuses the Call for an almost frustratingly long time, but can we really blame her? As Cortez observes, “whatever you do, your life will change forever.” We kind of accept the Hero’s Journey as a framework, but one to be moved through quickly when it appears; we don’t often really consider whether we’d blow off friends or obligations to chase fairy tales for an afternoon, just in case there’s something to it.

But then, neither does A pril, exactly. In the first chapter of the game, she spends most of the day working on her project; she even works a shift at the cafe where she’s criminally underpaid, along with her closest friends. But the effort she goes to that first day to play along with Cortez’s oddity is not trivial. She spends some of the little money she has on a weekly subway pass she has no way of knowing she’ll need several more times in short order; she spends valuable time she could be using on school work to navigate some truly ludicrous puzzles to receive the answers she was promised and denied. But somehow she accepts that there are answers to be had, on the word of Cortez alone; April may protest, may insist she doesn’t believe (though some of that depends on what dialogue options you choose), but by the very nature of her continuing forward she must accept the possibility at her core.

pril, exactly. In the first chapter of the game, she spends most of the day working on her project; she even works a shift at the cafe where she’s criminally underpaid, along with her closest friends. But the effort she goes to that first day to play along with Cortez’s oddity is not trivial. She spends some of the little money she has on a weekly subway pass she has no way of knowing she’ll need several more times in short order; she spends valuable time she could be using on school work to navigate some truly ludicrous puzzles to receive the answers she was promised and denied. But somehow she accepts that there are answers to be had, on the word of Cortez alone; April may protest, may insist she doesn’t believe (though some of that depends on what dialogue options you choose), but by the very nature of her continuing forward she must accept the possibility at her core.

“I can pull a rabbit out of a hat!

I can pull a hat out of a rabbit. What’s your point?” – April and Roper Klacks

The longest journey in The Longest Journey is the first few chapters, before April really knows what’s needed of her. Playing again, these portions – which also contain the game’s most illogical and unnecessary puzzles and least-interesting world-building – lost the quirky charm they used to have. When you’ve played an adventure game once, one or two terrible puzzles are excusable, and give the game a certain “what were they thinking there?” character. On repeated plays they feel like the chore they really are, the adventure genre equivalent of long hallways filled with enemies or “kill 10 wolves” quests.

But April eventually starts to uncover the conspiracy that has shaped two worlds, and once that starts moving things get better. Discovering secrets. Learning who the players are. Meeting one of the more vibrant characters in a game full of vibrant characters in the form of the foul-mouthed, legless hacking expert Burns Flipper, who elucidates Stark’s 23rd century culture by being clearly outside it.

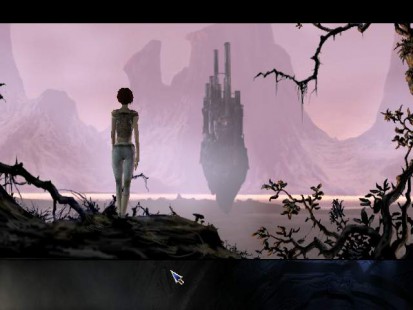

But there is only so much April can do in Stark, and her journey soon takes her to Arcadia. The Stark portions of the game (fittingly, perhaps) had left me feeling a bit cold, despite having some good components: characters I cared about, moments of humor. But Arcadia is where the game truly lives. Arcadia is a classic fantasy world in many ways, with thriving societies and magic that takes the place somewhat of science, while some aspects of life are still decidedly medieval. But blessedly it eschews elves and dwarves for a more novel cast, and a world more new and fresh than most video games provide. April’s journey takes her through what must be only a mere slice of Arcadia – one major city, Marcuria, the nearby forests, and a distant island – though much more is spoken of, and even in the little bit April sees she meets the comfortingly salt-of-the-earth Benrime Salmin and the memorably prejudiced Captain Horatio Nebevay, the sea captain whose faith in a deity called Mo-Jaal is one of convenience, and who hates sea shanties; she meets Roper Klacks, the fearsome alchemist, whose powers are buoyed by the disruption of the Balance; she meets Abnaxus, whose people, the Venar, perceive time all at once; she meets Crow (nee Bird), a faithful comic relief avian companion. She meets the matriarchal Maerum and the storytelling Alatien, the burrowing Banda and the mysterious Dark People, and stickmen and snapjaws and Orlowol. More than can be adequately explored in one game – in, really, half a game, since Stark is a frequent setting, too.

“The past – who needs it?” – April Ryan

Finishing The Longest Journey, I knew I hadn’t had the same experience I had in 2005.

That shouldn’t be surprising, obviously. But more than any other entertainment medium, I think, video games have a precarious aging process. I can go back to a novel I read in middle school and find it much like I remember, even if that provokes different feelings in me. What it did well often does not change; I just process it differently. But video games, of course, evolve very quickly; maybe that’s just because the form is so young. Maybe a hundred years from now there will be few fundamental upheavals in design. Maybe not. It is difficult to think of game design as a finite well, but it is also difficult to sit back and think of what hasn’t been done.

The Longest Journey does not suffer much from the progress of technology. The character models are low-poly but the pre-rendered environments are gorgeous. Adventure games often had that advantage: the environment itself didn’t have to be dynamic, or at least not very dynamic, in the way that it does in an action game, and so they could thrive on fabulous vistas.

Where The Longest Journey does not age well – or perhaps does not age with me – is in its gameplay. I know I used to love these things, and The Longest Journey was quite good as a game, relatively, inflatable ducks notwithstanding. Now, though, all the puzzles feel so obligatory in some ways. It has moments of puzzles well-integrated into the universe, Myst-like, but many of the inventory puzzles in particular are tedium; padding. There is a point when the puzzles become very logical, straightforward affairs that required mostly just an awareness of April’s tasks and the world around her, producing a thumping forward momentum that felt satisfying to complete but didn’t slow things down in the least. But larger portions of the game require logical contortion common to the genre, even now, that I suppose may appeal to a certain player, but for me…well, here I just want to get more of April’s story.

If The Longest Journey were made today, it would be almost certainly rather along the lines of a Telltale game, I think: the hurtle toward cinematicity in games in the last 15 years has created many things, but one of them is a tolerance for games that are essentially well-produced interactive narratives. One wonders how close Dreamfall Chapters may cleave to this model, versus being what its predecessors were.

Then again, would April’s story have mattered if we could decide how it ends? I think not. Indeed, on the basis of The Longest Journey alone the only thing we can really say about the ending is that there is none – only an intermission. The Longest Journey stands on its own, offers a complete story, but tantalizingly hints at the greater play of which it is only one act.

“Magic is not knowing.” – Cortez

I am left, then, wondering this: is The Longest Journey one of my favorite games, as I’ve so often said in the last decade? If this had been the first time I played it, I wouldn’t be able to say yes; I’m easily distracted now – a trait I don’t relish – and the game made me jump through more hoops than I’d’ve liked. I do not think this reaction is borne of the fact I’ve already played the game once.

And yet.

And yet I know that The Longest Journey has shaped my tastes considerably: indeed, shaped me, as a player, as a designer, as a storyteller. None of the parts I fixed in my mind as truly admirable proved particularly less so; I never put the puzzle design on a pedestal even as I professed it was better than a lot of its contemporaries, and I knew from the start that the focus on story wasn’t for everyone.

And so here I am in 2014, wondering what has changed since 2005. Everything. Nine years. I was April’s age when I played the first time. Now I’m old enough to be jaded, and look back on that period of my life and wonder if it was worth it. Old enough to be jealous. But this is the point, I suppose, of the entire exercise: April discovers herself throughout her journey. Perhaps it is only fitting if we discover some part of ourselves too. That’s why I can’t shake my affection for this game. Nor do I want to.

“The longest journey is the journey inward, for he who has chosen his destiny has started upon his quest for the source of his being.” – Dag Hammarskjöld

E-mail the author at dix(at)tap-repeatedly.com, or follow him on Twitter at @blueofthekin

Burns Flipper was such a great character. I’ve always been ambivalent about TLJ (played it around 2008 I think), although I lean more towards having enjoyed it. I never got around to Dreamfall.

I think my biggest gripe with the game was the character of April Ryan herself. She seemed so self-centered and shallow, but actually that may have been the point, so as to contrast with her growth. Even at the end though she was still kind of annoying. 🙂

I get that some people have problems with April but I don’t really sympathize with them. She doesn’t seem that way to me now or when I played this the first time; she always struck me as outgoing and engaged by things.

I think my favorite character, just from a writing standpoint, though, is and always will be Captain Nebevay. His faith-of-convenience amuses me, and I’ll still occasionally curse upon Jaal’s pus-filled eye.

This was a great piece of work, on a game I never played much of for whatever reason. Your recollections of how the game affected your thinking then, and how it’s influenced it over all these years, is surely a sign of how much impact The Longest Journey had on most people. It takes some courage to revisit something like this, something that was so meaningful. Memory tends to show only the best of things we’re fond of, and it can be kind of heartbreaking to go back and see the whole picture. I’m glad that you were able to take the bad with the good here. Says something about the quality of the game, that you could.

April was always my favourite thing about The Longest Journey. My least favourite thing about it is the glacial pacing and the lack of shortcuts to, e.g., bypass travel animations, or zip through dialogue more promptly. It’s the latter that’s led to my stalling twice with this game, at about 8 and 12 hours in each time (most recently last year, IIRC). I’m sure there’s a nice story under there – a good story in the world of games – but it makes me work for it like Robert fucking Jordan.

Loved your thoughts on this, Dix. I don’t know if I even managed to play 10% of the game (I did get to Arcadia) but I do regard it highly. It has this allure; almost pure nostalgia I suppose. And I clearly didn’t even get to the good stuff. I think the pacing might bother me today too, whereas when I first played it in … I don’t even remember what year, the slowness might have been a boon: a game for an entire season; it always seemed like an appropriate game to play, at the exclusion of all others, over four or five wintery months. Insert long journey quips.

Your article has very much made me want to play TLJ again.

Great article! I played TLJ for the first time in 2011. I was not hugely impressed by the puzzles but I was profoundly moved by the story. The glacial pacing mentioned above was part of my affection for it.

Most importantly for the game, April Ryan was exactly the character I needed at that time. I was just finishing a prolonged college course load, but I had also developed a very steamy and romantic relationship with a lovely woman whom I had just helped move over 1800 miles away.

In brief, April Ryan was that woman in many ways. She is written so realistically that I didn’t feel like I was projecting on her, but that April Ryan was projecting on me. A very powerful experience.